Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my pleasure to welcome Felicity Abbott. In this interview, she talks about the competitive nature of her field, choosing her productions, building environments to be seen by the camera, and how the industry has evolved in the age of Covid. Between all these and more, Felicity dives deep into her work on the mini-series “The Luminaries”, and the recently released “The Invitation”.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Felicity: I completed a four-year fine arts degree in New Zealand, which is where I’m from originally. The thing that I appreciated was that it developed my conceptual mind. I was also studying art theory, art history and various philosophies and criticisms, and it was beneficial for training my conceptual understanding of color theory and the theory of art, but also modalities of sculpture and physical space.

Afterwards, I decided that what I enjoyed the most about art school was the collaboration. Even though we were intended to pursue careers as solo artists, I really liked the discipline of all of my colleagues in the studio together, and that sharing of ideas and participation, even though our work was quite singular. So quite shortly after graduating I decided to pursue something that was more collaborative in nature.

I’d always been passionate about cinema. Growing up in New Zealand, I watched every single foreign film I could get my hands on. It wasn’t that much about American movies, but I was a great fan of most European cinemas, Eastern European cinema, Japanese, Korean, anything that occasionally would float through New Zealand screens. I suppose that I was so interested in the world, growing up on a tiny island at the bottom of the South Pacific. And then I discovered there was this thing called artistic direction for theater and opera but there were no specialized courses available in New Zealand -nor production design, which I wasn’t aware of at the time.

So I was investigating other countries in the world where I could study artistic direction, and I found a path through to a British production designer (Michael Kane), who was working in New Zealand at the time on a film called “Once Were Warriors”. He encouraged me to pursue postgraduate study, and he was kind enough to mentor me. I did some early work as an art department assistant on features in New Zealand, and then decided on the Australian Film and Television School, which I applied to do a master’s and was accepted. I did a two year master’s at the Australian Film and Television Radio School, and from there I went to study in Paris at the National Film School, La Fémis, for a period to complete my master’s thesis. That was my study and experience.

Concept art for The House Of Many Wishes on “The Luminaries”, courtesy of Felicity Abbott.

Kirill: Were there any particular surprises for you when you left the world of studies and joined the real productions?

Felicity: We had a great program. I was very fortunate to go through AFTRS at the time, where Stephen Curtis was the head of design. He’s a great design educator and a designer for opera and theater. He brought a lot of industry mentors in, and we had to complete an entire feature as a part of our program. So I was working with a very talented production designer called Michael Philips, and I did an entire feature as his art department assistant.

Those are the most valuable experiences for me, because they were hands on. Of course, they were not paid positions, and I was still a master’s student. But the practical experience was invaluable. I could see not only the way that the art department runs, but also the personalities came together, how the hierarchy of the department functioned, how the interpersonal relationships work, and how the collaboration between the production designer, director and cinematographer work. The latter was of most interest to me, as that formed the basis of my master’s thesis – the relationship between production design and cinematography.

I art directed two projects, and quickly decided that I was much more passionate about production design. So I pursued short films. I did about 20-25 shorts that were unpaid opportunities. They were great projects to explore ideas, and continue to focus on the relationship between production design and cinematography.. I kept on designing until someone offered me a paid project, which was quite a long time after I graduated. It was about six years until I got a feature length project as production designer. That’s certainly not everyone’s path, but I was determined that I wanted to either assist a senior production designer or work toward designing my own projects. I designed a lot of dance films early on, quite experimental stuff, which for me was an extension of the conceptual ideas I focused on at art school and the techniques learned at film school, and continuing those collaborations.

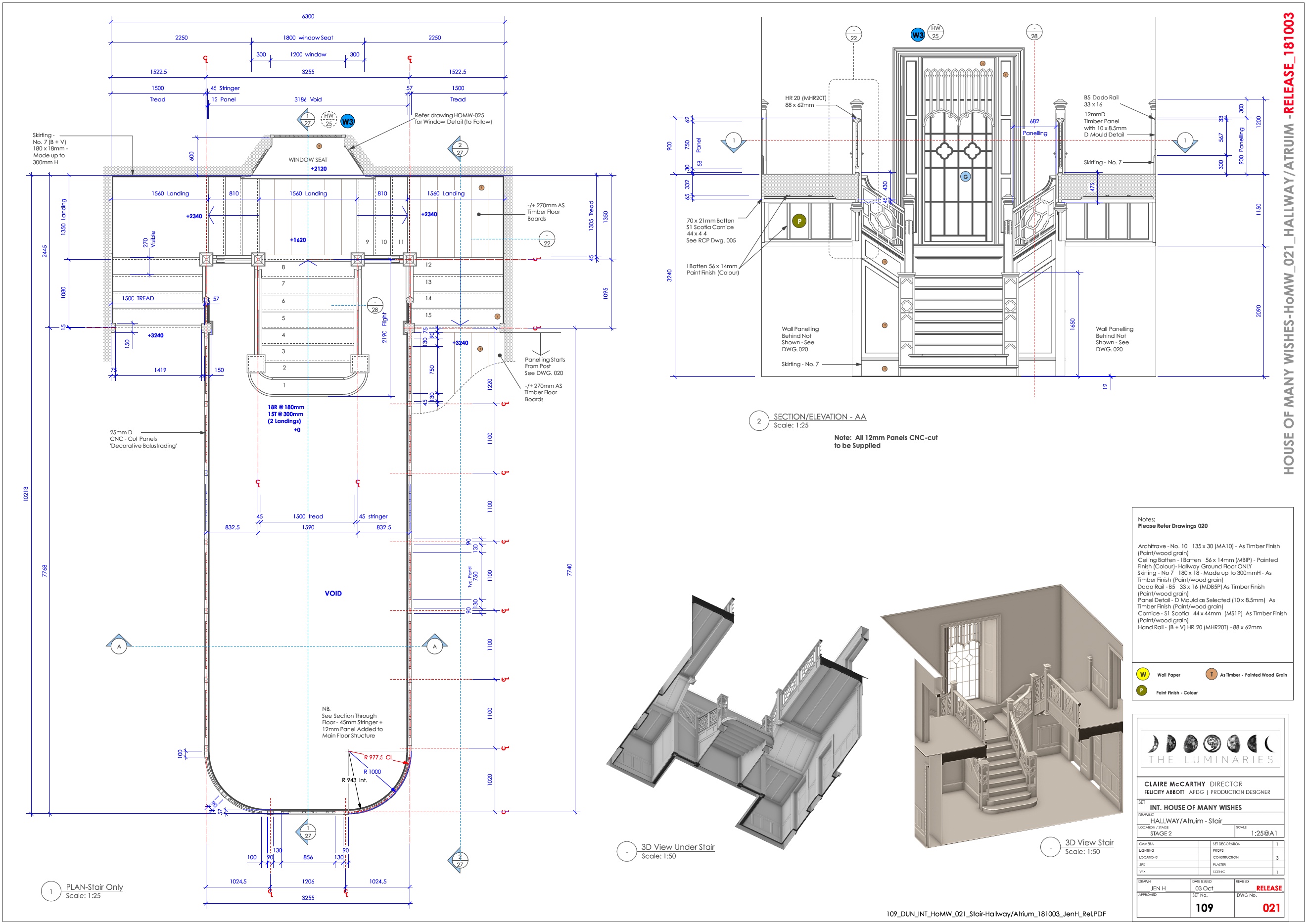

Construction drawing for hallway / atrium for The House Of Many Wishes on “The Luminaries”, courtesy of Felicity Abbott.

Kirill: Speaking about art school and film school, and people going down different paths, if somebody asks you “How do I get into this industry? How do I get to be a head of a department?”, do you feel that going to a film school and doing a master’s degree is a good stepping stone?

Felicity: I really think it depends on so many things these days, mainly because it has become very expensive to study, and for a lot of people that’s prohibitive. I certainly don’t think it disadvantages people if they do not complete a degree per se. I know many people that have come up through the industry, which is an equally valid pathway.

However, from my own experience, both experiences were equally valuable. They taught me different things. Film school was much more focused on practical and skills-based training. Learning techniques and having as many skills as you can is important. Developing your mind and gaining life experience is also valuable. One needs a range of tools. Film school has a limited capacity to demonstrate the day to day experience of how the industry functions.

There are so many really mundane things. How much should we be paid? How to represent ourselves as artists in a business environment? That’s something that is rarely spoken about in creative courses [laughs], but they’re important things that you need to know how to best represent yourself or how to seek representation in the industry. There’s a lot to be said for a bit of both. If I was advising someone now, I would say probably short courses are possibly a good option, as they’re more achievable financially. And then, unfortunately, it still is the case where people often end up having to volunteer. I certainly don’t support working for free in the long term, but I did my time like most other creatives that I know.

I completed two or three feature projects as an unpaid assistant, just to learn – and then certainly some shorter periods of offering my services to get in the door. Also I’ve had a lot of people approach me in that same capacity. I’ve taken people on after they’ve done a couple of weeks as a volunteer, moving them into a paid position. It’s not ideal, but unfortunately that’s still the nature of the industry. It’s very competitive and if you lack contacts, which a lot of people do, then seeking work experience and being patient and persistent can eventually pay off.

I don’t really like that “starving artist” cliche. My approach is that if someone regularly and consistently contacts me for an opportunity, I’ll offer them something small as a casual assistant if I can. Maybe they can come and do a short period of time, or part time even, which is more sustainable if people are working in other paid jobs. And then if they’re skilled, they can move up quite quickly.

Building out Dunedin Street on “The Luminaries”, courtesy of Felicity Abbott.

Kirill: Maybe it’s a cliche, but does it feel that there is maybe not enough paying jobs for everybody that wants to be in this industry?

Felicity: I don’t think there is. I’ve worked in a lot of countries, I’ve lived in five different continents and worked in many different industries, and training is very important. To speak to your earlier question, I don’t necessarily mean formal training at a film school or art school, but rather that industry training and mentorship are very important.

I was fortunate to have a few significant mentors at different points in my career, and I have tried to return that to the younger generation of production designers. We need formal initiatives to encourage that. Personally, I think the film industry can do a lot more for facilitating training, but it’s often not the focus of a production environment. The Art Directors Guild, which I’m a member of, has a formal production design training initiative. This is a funded program designed to provide mentorship, supervision and on-the-job training to future Production Designers and Art Directors.

We need more of these initiatives, but also specific projects that take on attachments or PAs or juniors. There are often insurance issues and there are obligations from the production point of view, so some productions will and some won’t. I feel that it’s our collective responsibility to train the next generation and to help facilitate that.

But the reality is it’s a competitive industry by nature, and there aren’t jobs for everyone. And also the industry may not be for everyone, which is why I encourage people to do a little bit of volunteer work and try out various roles within the art department. A lot of people quickly find they don’t like it at all, and that’s understandable. It can be a challenging and difficult industry.

Kirill: So it’s not all red carpet and champagne.

Felicity: Certainly not in the art department [laughs].

Building out the Hokitika town set on “The Luminaries”, courtesy of Felicity Abbott.

Kirill: Do you think anybody can be trained on the technical side of things? And do you think anybody can be trained to become an artist?

Felicity: I think people can be trained in the technical aspects of the craft, and that should be ongoing. I continue to study and train and upskill and educate myself -as most production designers, I’m sure, do.

The conceptual and creative side of design is more intuitive for me. The creative sensibility is much more innate. I’m speaking as a production designer that comes from a fine arts background, and I’ve always had that sensibility. Obviously, production designers come from many backgrounds, and I’m sure that’s my individual path. I approach production design as an artist because that’s how I observe the world. That’s how I intuit my surroundings and interpret character and narrative.

I’ve often said that color is my first language, and I see things in this way. I use color intuitively to create a mood and tone and to explore the poetics of a space. This approach is significant for me as an artist and production designer, and I don’t know if that can be ‘learned’. I suppose you can understand them from an intellectual point of view and these qualities can certainly be developed with experience. But I think as an artist, you’re driven to do that because that’s simply the way that we perceive the world. It’s significantly different from other disciplines, I suppose.

Shooting on the Hokitika town set on “The Luminaries”, courtesy of Felicity Abbott.

Kirill: I was reading one of the interviews you did on “The Luminaries” and you said that production design is architecture of the screen. Can you expound on that a little bit?

Felicity: That was an interesting project because so much of it was built from scratch. We were building towns and creating that world, and that intrigues and fascinates me as a production designer from an architectural point of view.

I’d distilled this from various articles and interviews that I’ve read over the years. Creatives speak about designing space, exterior or interior, and I’ve always loved architecture as a discipline. I did not want to be an architect myself, but one of the things that I love about production design is the opportunity to build and design sets. It’s very different from architecture per se for the domestic or commercial market, because primarily you’re viewing things from the camera’s point of view. It still involves the formal design of a space, but it originates from a specific narrative space, and the considerations are all driven by the story and the camera movement.

It was a lengthy project, just a bit over a year, and we built towns, boats, hotels, and bars. It was the closest I’ve ever felt to being an architect, because we constructed so many buildings and spaces. It was a fantastic, exciting, and creatively rewarding project. I get to work with set designers who do the technical drawings and who often have more of an architectural background than me. It’s a rewarding collaboration between many disciplines.

It’s extraordinary that you can have a job that allows you to be involved in designing many spaces – and then very quickly, relatively speaking, to see them come to fruition, and be walking through these towns and then in turn to witness the actors when they come into the world to inhabit their character sets. That’s extraordinary. It takes design to the next level. As an architect, you would deliver it to an individual or a family, and as a production designer you hand these worlds over to a director and the cast to inhabit and develop their performances in that space.

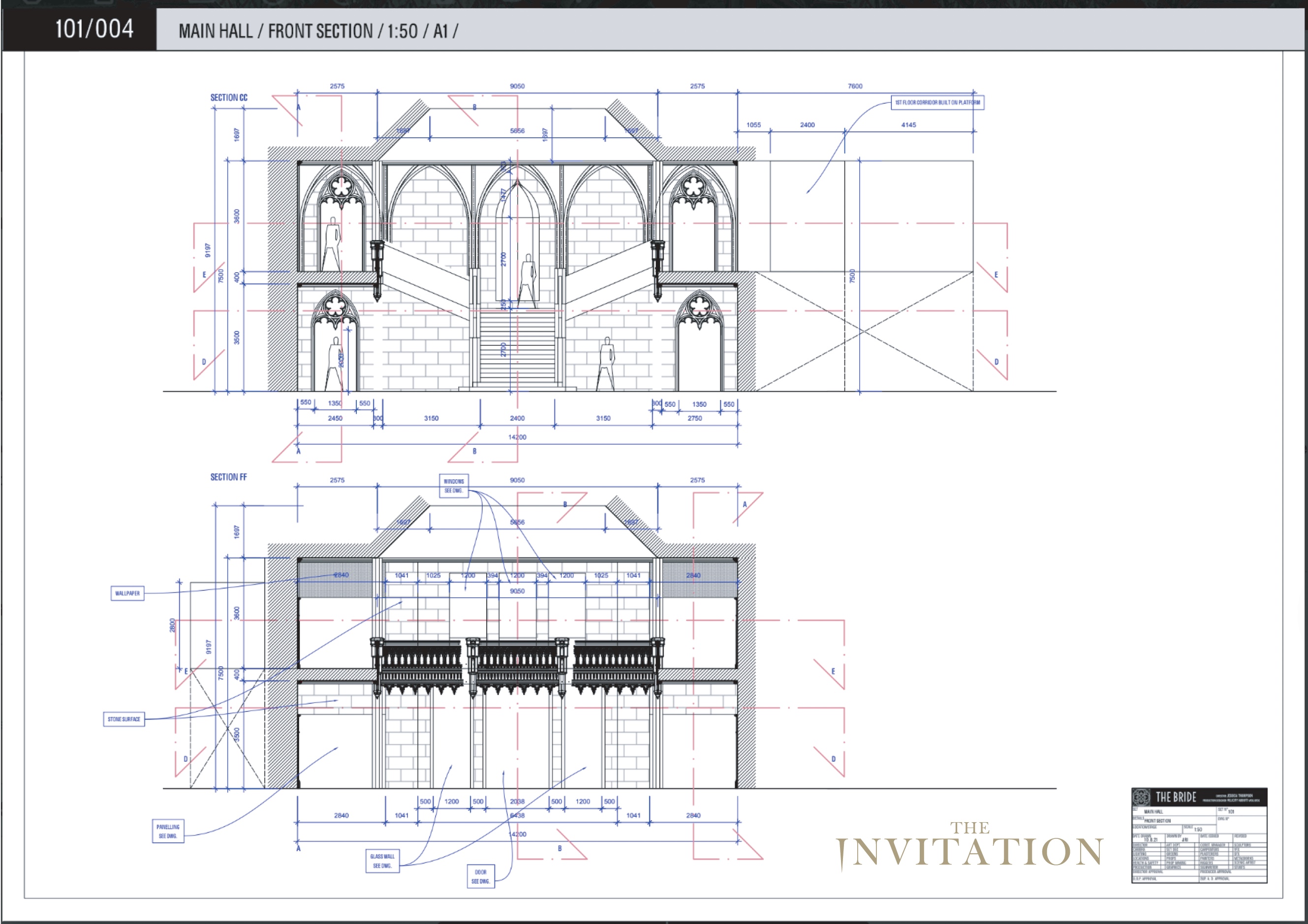

The main hall set on “The Invitation”, courtesy of Felicity Abbott.

Kirill: Jumping forward to “The Invitation”, it was a mix of shooting on locations and building sets. Do you have a preference between building a set like Evie’s bedroom or that grand hall from scratch, and taking over an existing space and augmenting it to fit into the story.

Felicity: “The Invitation” had some significant constraints. The story was set in the UK and the US, and we were filming in Budapest, Hungary. Location was significant, because the majority of architecture in Hungary is Austro-Hungarian, and there was one rare example of Tudor Gothic or English Tudor architecture, which became our exterior location. The location was filmed as the exterior of New Carfax Abbey and the majority of the interior sets were built on stages. We use the exterior grounds, and then one or two smaller rooms within the castle itself.

The main reason to build the grand hall set from scratch was to achieve the scale and sense of symmetry – a grand atrium and various corridors going off it, is that it’s quite rare to find that scale of space in a location. The scale, tone and architectural symmetry were important to the story.

I always prefer to build a set to have complete control over not only the palette and the textures and surfaces, but also the sight lines, which are very important from a performance point of view and the camera point of view. If I have the choice, I would always prefer to design an environment from scratch to give the director complete flexibility and in order to match their intention from the storyboards and the script.

On the finished set of The House of Many Wishes on “The Luminaries”, courtesy of Felicity Abbott.

Kirill: Do you find that it was “interesting” to build something gothic and intricate for this horror story in that castle, compared to maybe Evie’s apartment in New York, which is something that we see around us in our everyday life?

Felicity: Both have their own unique challenges. For me, they were both rewarding because they were designed and built in Budapest – even Evie’s New York loft apartment. They required research into the correct style, architecture, the view out the window. It was a much smaller scale set than New Carfax Abbey, and it was right toward the end of filming. It was, maybe, the last set that we filmed in.

But honestly, I love them all. I visualize the space in my mind, and then they’re designed, and then a team collaborates to bring them to life, and then suddenly I’m standing in that space in the moment. It really is the most magical, extraordinary experience being part of the creative team that produces the visual narrative. I get such a thrill when a set is finished. The final touches, the scenic art is a very important process for me – working with the artists and the painters that bring that set to life. Then the set decorator and their team go in to create all that character and detail.

So when our process is over and it’s handed over to the director and the performers, at that point I walk away. That’s the point where I say goodbye to it, because that part of the creative journey is over and then it goes on to become something else.

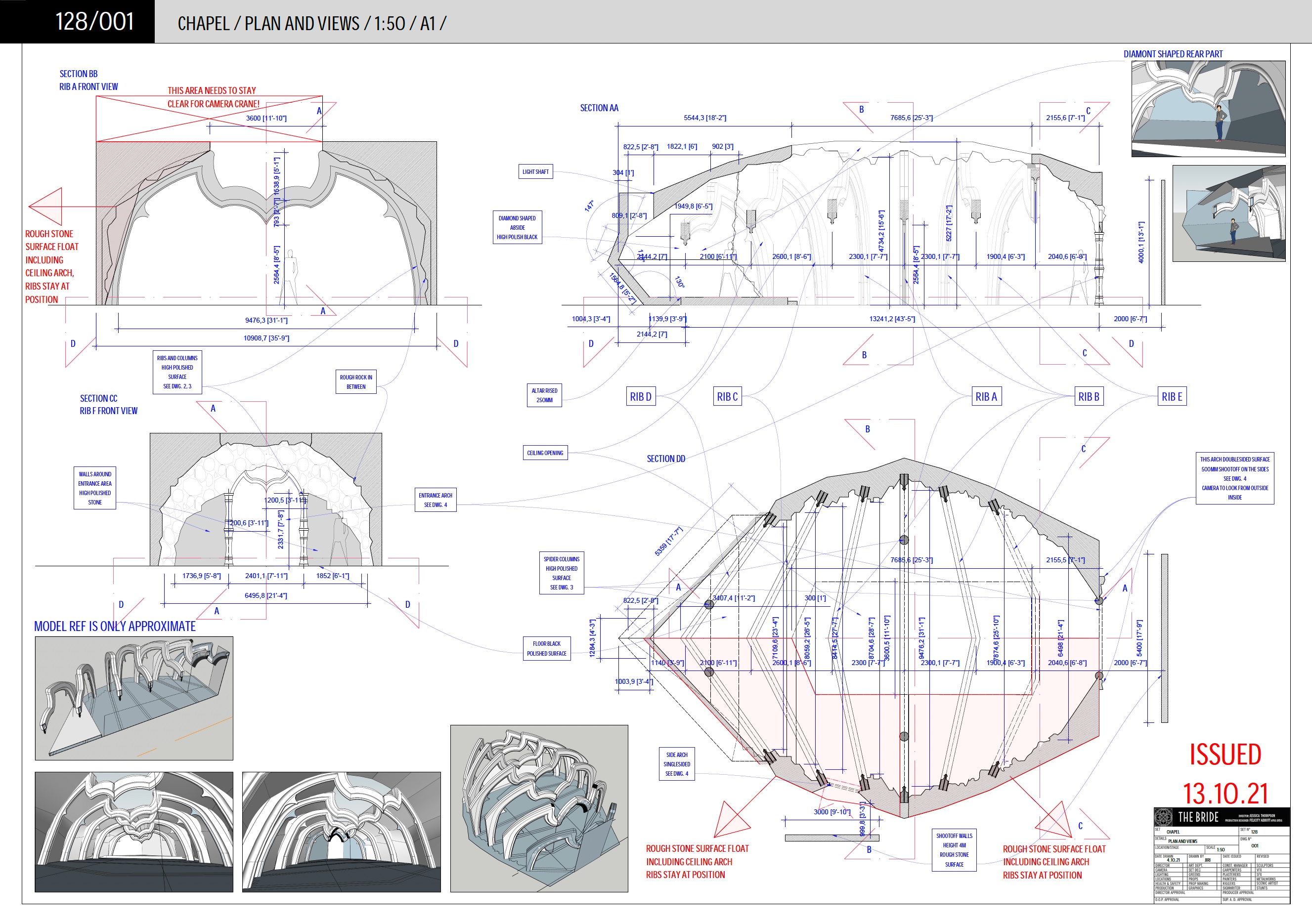

Dragon statue concept art for “The Invitation”, courtesy of Felicity Abbott.

Kirill: Do you sometimes wish the camera would linger a little bit longer on the set pieces, and maybe a little bit less on the actors?

Felicity: If the relationships are strong between the collaborators, then the design ends up being informed by what the camera needs, what the story needs, what the director’s intentions are. For myself, the best projects are where there is a great collaboration and pre-production, and therefore nothing is wasted.

Certainly earlier in my career, and this is probably true for many production designers, I had the experience of building something that was very rarely seen, which was disappointing. For me, it was disappointing from the point of view of effectively utilizing resources. Every project has budget limitations, and so you want your resources to be telling the greatest story possible. But this can be indicative of a lapse in communication, where the key creatives are not on the same page, possibly.

Having said that, I do enjoy the moments before the camera arrives, where it’s just me and my department. And as much as I enjoy seeing the actors in the spaces, I also enjoy the spaces for themselves, because hopefully they have their own story.

On the finished set of Gascoigne Cottage in Hokitika town on “The Luminaries”, courtesy of Felicity Abbott.

Kirill: Does it feel sometimes a little bit random which productions you join, in the sense that your availability has to match the productions availability, or that a particular production maybe is not coming to a country that you are based in?

Felicity: I’ve been lucky to work all around the world. I’m more likely to attach myself to projects for their creative potential, and also for the people that are involved in them, both of which are very important to me. I also love to travel. I love the challenge of working in different countries with different creative teams, and also the challenge of creating one country in another country which filmmaking often challenges us to do. Those are my priorities when I choose a story.

When I read a script, I know quickly whether it resonates for me or not. Someone asked me this recently, and I thought about it for a while. For me it’s whether I visualize it or not, and I find the projects that I design, I just see them instantaneously. It’s like the imagery starts to rise off the page as I’m reading it, and that’s when I know that there’s a significant story, there’s a visual narrative to tell. And if I don’t experience this, then quite often they’re not projects that I end up doing.

Sometimes I have to read a script a couple of times, depending on the genre and depending on what the story is, but I do find that for most of the projects that I’ve designed, I had a strong, almost instantaneous response to the material.

Set shoot of Godspeed boat on “The Luminaries”, courtesy of Felicity Abbott.

Kirill: What about your major collaborators? Do you feel that there needs to be certainly a clash of opinions, clash of ideas, or do you feel that it needs to be a little bit more in sync?

Felicity: Within my own department, there definitely needs to be a cohesion of ideas between my key collaborators that contribute to the vision and look of the film – the set decorator and the charge scenic.

As for creative differences of opinion between directors and cinematographers, and production designers, it varies. It’s been a great experience for me to work with accomplished directors like Bruce Beresford, with whom I’ve worked on a couple of projects, and his cinematographer Peter James, who is also extremely experienced. I worked with them on a project called “Ladies in Black”, which was probably the most effortless in terms of collaboration, and part of that is working with such consummate filmmakers. Every day on set with Bruce and Peter was a masterclass in filmmaking.

Even though I’d been in the industry for quite a few years when I worked with them, I found those experiences really joyous, because there was a synchronicity between the creators and the vision, and obviously it’s driven by the director. Conversely, sometimes you can work with less experienced directors, who maybe aren’t as sure of themselves and feel they have more to prove.

Godspeed boat at Dunedin Quay on “The Luminaries”, courtesy of Felicity Abbott.

Ideally, a director is confident in their vision, regardless of their experience and will allow their creatives the space to do their job. That’s the key. That’s when you get a good collaboration. And of course there are occasionally differences in opinion. That’s part of the creative process. Directors should hire people because of their ideas and expertise, and then entrust them with their vision. It certainly doesn’t work to micromanage artists. I don’t think anyone appreciates that. There’s a lot of trust to be had. And it’s definitely more about confidence than years of experience or number of credits.

When I’m interviewing for projects or meeting directors for the first time, I think it’s a good thing to discuss the process and how you like to work. I always ask directors about how they like to work with production designers. What is their experience, how has that relationship been for them? We all work in different ways.

I see myself as a filmmaker, although I’m quick to say I’m a production designer. I have no aspirations to direct, I love my craft. I want to achieve the best for the film. But as a designer, I have my own ideas. I will have lots of questions on the script in order to lead my own creative team. I’m passionate about cinema in general. I often say to directors that if they want someone that’s going to do what they expect, then I’m probably not the right person to hire. Whereas if they want someone to engage fully and elevate the story through the visual narrative – which is what I believe the role of production design to be – then it can be a great creative relationship. Some directors don’t work in this way, and I absolutely respect that. But these are good conversation starters to find out whether something’s going to be the right opportunity or not.

Construction drawing for the main hall for “The Invitation”, courtesy of Felicity Abbott.

Kirill: Going back to “The Invitation” and that grand hall, how much time did it take to design and build it?

Felicity: That was our largest set, and we had the most preparation time for that. It involved an initial design process of research and development, and then about 10 weeks of construction, which also involved scenic finishing, set finishing, and the set decoration. And then there was quite a large pre-light. Then the set is handed over to the lighting and rigging crew, and we had stunt rigging going into that set as well. There was a lot of collaboration between various departments with the art department to determine rigging points, lighting, camera ports and other things.

It was a multi-storied set, so there was a lot of structural engineering involved also, which is again that architectural connection. There are often engineering and safety requirements that go into set design and construction.

Building the main hall set for “The Invitation”, courtesy of Felicity Abbott.

Kirill: What about the big sculptures next to the stairs?

Felicity: The sculpture of St George and the Dragon was something that was designed from scratch in 3D, fabricated, and then handed to artists for a scenic process. I wanted the finish to reference a titanium oxide patina on bronze. I didn’t want the green patina that you often find on bronze. I wanted it to have a brightness to it over the bronze metal, because the set itself was so deeply saturated in color. It’s quite low light in there, so it was a nice contrast that the dragon and George stood out from the walls.

And that had to be purpose built, because there were stunts involved when the spear became a special effect. We had a soft version (for the stunt) and a sculpted version of the spear. There was a lot of interaction between other departments into that, and that falls under the category of set decoration. It went through the normal design process, but technically it was a piece of set decoration. We outsourced that for fabrication, and then our set decoration painters did the final scenic finish on it.

Building the main hall set for “The Invitation”, courtesy of Felicity Abbott.

I’m a huge proponent of doing as many camera tests as possible. Formally, there are usually costume, hair, and makeup tests in a pre-production on a film. But I request camera tests that are specifically for the art department, because I think they’re so important. So we had a couple of camera tests where we prepared a section of the set wall with all its architectural moldings and the options for paint finishes. Quite often at that point, I will pick a certain color range so we can test the levels of saturation, the level of sheen and the relief textures and moldings. So we had the first camera test, and that informed what needed to be adjusted.. And then did a second camera test, where the set was very close to where it ended up.

These tests are instructive under the various lighting conditions. They inform so much of my creative process, and the design decisions we make in the art department in terms of color saturation, tone, texture and sheen.

Building the main hall set for “The Invitation”, courtesy of Felicity Abbott.

Kirill: Is there much difference between how the eye sees it and how the camera sees it?

Felicia: There’s quite a big difference. A great scenic artist once said to me when I was still at film school, that if you squint your eyes and look at the finished set after the scenic process is complete and it looks correct, and to your open eye it looks slightly heavy handed – that’s fairly indicative of how the camera will read it.

Obviously, it very much depends on the lighting of the set and the genre, because certain genres call for a more elevated scenic finish. But generally speaking, in terms of naturalism, especially when you’re looking at a set that’s built and aged, that generally holds to be true. If you squint your eyes, it’s a general representation of what the camera would see.

Conversely, I worked on an opera for Bruce Beresford, the film director that directed about nine operas. And I had a great scenic artist, who was a senior Australian film scenic artist, and he was working with me on this opera, and we had to keep redoing the scenic because we would sit in the theatre and look at the set, and you just could barely read the ‘age’ and scenic finishes. We were both bewildered, because it ended up as something that looked absolutely terrible looking at it in the natural light of the workshop. But then when you sit back in the audience, it read perfectly. That was a great education for both of us. This guy had done 40-something films, an outstanding scenic artist for film, but neither of us could believe how heavy the age and the scenic needed to be in order for it to read from the back row of an audience. It’s such a different craft than film.

Camera crane on the finished main hall set for “The Invitation”, courtesy of Felicity Abbott.

Kirill: Would you say that Evie’s bedroom in the castle was the second biggest set that you did?

Felicity: We built a few sets of a similar scale – the library, bedrooms, the dining hall. They were scheduled one after the other. There were some sets that were built that are not seen in the final film. The largest set was the main hall, and then we built about eight or ten other medium-sized sets, some with corridors attached.

Kirill: What do you remember from the bedroom?

Felicity: The idea with the bedroom set was that it was supposed to be a dramatic environment that would be quite seductive for Evie. The design premise was to appeal to her sensibilities as an artist, and for it to be engaging and intriguing, with an elevated, contemporary tone. The whole of New Carfax Abbey was designed with that intention, it was something that the filmmakers talked about a lot.

We see the bedroom set in a different moment in time where her descendent Emmaline is locked in the room. So there had to be a relationship between the two rooms, and I suggested the idea of the painted walls. It looks like wallpaper, but they were hand-painted walls. And then we had two iterations of those, one in Emmaline’s bedroom and then one in Evie’s. They’re in the same room, and I hope that’s clear in the film. Obviously, it’s much less saturated in the past, as it was a lot lighter and more ethereal.

It was as if Walter had decided to renovate the family mansion in a contemporary Gothic style, which stylistically holds true historically to what the architecture would have been. Yet the palette itself is saturated, contemporary, and bold. So that was the idea behind it.

Concept art for the wallpaper for Evie’s bedroom for “The Invitation”, courtesy of Felicity Abbott.

Kirill: Did you do anything particular in the scene where they go to this big bath and they have their spa day? I understand that it was filmed in an existing bath in Budapest.

Felicity: Yes, it was. It was closed to the public. For that one, it was mainly set decoration. We didn’t change the color palette there. We dressed the lighting and all the furniture in it and built in some of the windows in order to create the right kind of mood in there. We plugged in some existing windows, changed the lighting, and decorated the whole thing. It was a beautiful bath that matched the symmetry of our other sets, but there were some contemporary elements that we didn’t want to see, so we covered the handrails and the water spouts. There are some extraordinary baths in Budapest from the Ottoman Empire period, but we weren’t able to film in those. It was great that we were able to find this location, but you don’t have a lot of control over those historic locations sometimes.

Concept art for Evie’s bedroom for “The Invitation”, courtesy of Felicity Abbott.

Kirill: How much disruption did you experience with Covid on this production, and in general in the last three years?

Felicity: On “The Invitation”, it felt like it had become almost normalized. For myself and for my department, we were all used to working with PPE, Covid protocols and wearing masks. We did that all the way through from pre-production. There are requirements that are set by the studio, really. So we had testing regimes and the wearing of masks etc.

There were positive cases on our crew, certainly in my own department, with some people being down for days here and there. It’s not too disruptive. It’s more tiring. It definitely takes a physical toll wearing masks all day, every day, particularly for the on-set crew. The art department comes and goes, and we have a bit more flexibility in terms of our daily schedule. But I think everyone finds it a lot more tiring, especially when you’re working in summer. And we started in the height of summer in Budapest, so it was very hot.

I was designing a production in the US when Covid closed everything in early March 2020. We had just started when Covid hit its peak, and it was the last production in the US to shut down. A few months later, once return to work protocols had been established, we were the first to start up again, because we were an existing production. So we were very much the guinea pig. It was a film called “The Unholy”, and I was thinking back to that the other day and remembering how surreal the whole experience was. We were literally in hazmat suits, because there was so much that was unknown back then in terms of virus transmission. There were so many protocols, for prep, shoot and for cleaning sets, all of the things that we now have a lot more information on.

Crew members on the finished main hall set for “The Invitation”, courtesy of Felicity Abbott.

Kirill: Does it feel like it’s becoming a distant memory, or would you say that it will be felt for a longer period of time going forward?

Felicity: Covid is definitely still present on every job. People in the crew still test positive. I believe that it’s mandatory in most countries that if you work in film, you have to be vaccinated. The strength of the virus seems to have dissipated and therefore the working protocols continue to be updated. You adjust.

There are so many things you have to adjust to constantly in the film industry. So for me, this is just another thing. It was much more disruptive in the early days when we had to work remotely, and that was the most challenging part – to make a film and not be in the same room as the director, or other members of my department, or the cinematographer, and have to do a lot of that work over Zoom or other remote mediums. But even back then we managed to find a way. We were designing sets, and then I would bring it up on the screen, and the director would be in Los Angeles and I’d walk him through the set. It was inspiring how adaptable the creative process can be. It’s also remarkable how adaptable humans are, and how adaptable this industry is. You always seem to find a way.

In some ways, things were improved. Gone were the days of 40 people sitting around a table having a very long production meeting. So some things were more expedient and streamlined.

That project was particularly interesting because we started off filming mostly on location with very few set builds. And because of Covid, when we returned around July 2020, the studio mandated that all the locations that we were previously filming in needed to be built as sets on stage, because we’d established one or two. So that for me was an interesting challenge, because it involved pretty much starting pre production again, but building everything as a set which you would never normally do for cost reasons. Usually productions choose locations because of their cultural heritage or their richness, but for the safety of the cast and crew and in order to control the filming environment, we built everything as a set.

Dining hall set for “The Invitation”, courtesy of Felicity Abbott.

Kirill: Speaking about how the industry adapts to changes, do you see big changes in how the younger generation is watching these productions? There’s such a wide variety of screens in our lives, and maybe not as many stories are being told on the big screen?

Felicity: Yes and no. I always watch that with interest, as certainly television is just so much more cinematic and sophisticated than it used to be. There’s some remarkable television being produced which is much more like film in its sensibility, and certainly larger-scale television productions seek filmmakers specifically. There used to be much more of a distinction between the two, particularly in America. Certainly in countries like Australia and New Zealand, most filmmakers used to go between the two because the industry wasn’t large enough to sustain a focus on one or the other.

That certainly changed things. I’ve also watched initiatives like Quibi that happened a few years back with the idea that filmmakers would make short-form content to be viewed on a mobile phone. I actually interviewed for one of those projects with a director who was a very well known American filmmaker. I asked her what she thought about making content for this tiny screen in terms of the level of detail and focus, and she said that she hadn’t really thought about it. And to be honest, I couldn’t see it succeeding. It didn’t surprise me at all that this platform was very short-lived.

I couldn’t get past the notion that you’re making expensive content to be viewed on this tiny little device, and that was the only life that it had. To be honest, I found that a little bit depressing. As someone that loves going to the cinema, that was the hardest thing for me during Covid -not being able to go and watch a film in the actual cinema. That’s such a ritual for me, and I enjoy it so much.

I love cinematic television, and there’s some series that I’ve watched that are very inspiring, and I’ve worked on a few of these projects – the Luminaries being one of them. But I also really love films. The reason I went to film school was to work on film, because that was what I was passionate about – that and the history and craft of production design in film.

Finished main hall set for “The Invitation”, courtesy of Felicity Abbott.

Kirill: So for your next feature production, whatever it might be, what would be your pitch to the audience to see it on that big screen in a movie theater, that they need to be in a movie theater to fully experience it?

Felicity: I don’t think everything needs to be seen on the big screen. But also, I believe that there are some films that absolutely need to be seen on the big screen. “Dune”, for example, is a great example of a film that absolutely needed to be seen in the cinema, because it’s such an immersive and holistic experience. It’s made for the big screen -not just for the expansive and richly detailed visuals, but also the soundscape, the atmosphere, the darkness. For me it captured the intimacy of an installation while maintaining the enormity of its world building. It’s a film, obviously, but it was akin to me being in an art gallery also and within a sensory installation. It was just such an uplifting and extraordinary experience.

I have friends and colleagues that watched it on their computers and were disappointed in the film, and I think they missed the point because it was not designed for that medium.

To answer your question, I work on projects that have potential in terms of visual narrative, and that’s why I encourage people to go to the cinema to see them. That’s where you see the richness, detail, and the intent of the filmmakers.

Concept art for the library for “The Invitation”, courtesy of Felicity Abbott.

Kirill: You mentioned that you love color. Is there such a thing as your favourite color?

Felicity: I really like blues. I like a good saturated deep blue. colors are so evocative of mood and they can really set the tone and sense of place.

I’m interested in secondary and tertiary tones and the intricacies of palette, in the same way that Corbusier designed color for his spaces in order for specific combinations to achieve a certain atmospheric effect and established a whole color keyboard. That’s very much similar to the way that I think about the meaning of color in narrative space, as sort of harmonies. I enjoy the exploration of color, tones and hues and the process of hand-mixing and deciding each palette with intention.

Someone recently made a comment on Evie’s bedroom and “The Invitation” and said “What is that green? Is it such-and-such manufacturer?” And I said that it’s all hand-tinted, created for the specific lighting conditions, and the tone, and what takes place in the set – whether it’s day or it’s night. The palette is created uniquely for the film and the story.

Evie’s bedroom on “The Invitation”, production design by Felicity Abbott.

Kirill: What is a successful production for you?

Felicity: For me, it’s always about ideas, first and foremost. And also, a successful production is one that has a decent amount of prep time. It’s not entirely about the level of resources, although that certainly contributes to it. But for me personally, you can’t compromise on the preparation period. On the best productions that I’ve been involved in, certainly “The Luminaries”, this was the case.

We had a long period of pre-preparation, which is invaluable for the design process. Unfortunately, it’s something that most productions never have enough of, and they look to me like they haven’t had enough preparation. But for me, that’s the difference between developing consecutive ideas, and being forced to go with the first idea or the first response. It was an enormous luxury on “The Luminaries”. There was an extensive research and development period phase for myself and the set decorator, supported by Working Title and the producers. It was a period of about five weeks just to research, because this was a complex period piece.

And then we had weeks with the director and cinematographer and myself, going through scene by scene and talking about ideas. It was something that I’ve only experienced on a couple of productions, but I think the end result speaks for itself. Every idea was able to evolve. The collaboration becomes intertwined and enmeshed at that point. You discuss and debate various solutions to creative problems. And it also makes a huge difference when you start shooting as well, I should say. Every production is challenging, regardless of the budget or the country or the conditions. And you fall back on that key collaboration, and those ideas, and that process when issues arise during the shoot.

Certainly for me, it is this design process that you have to quickly draw on for creative solutions to problems that invariably present themselves during the shoot. And that’s the relationship that you develop in pre-production. If your pre-production is not long enough or it’s compromised, it can make a shoot very difficult.

Understanding this comes with experience. I’m much better at discerning whether a production has sufficient resources or time allocated in terms of what they want to achieve. I should say it’s never enough, even on bigger movies with larger budgets. But the satisfaction comes when you have that richness of collaboration early on and you have time to distill those ideas and work through solutions with a great creative team, with enough time to execute it. You see the results of that on screen, and that for me is the satisfaction. That is the ideal process, when you can see those through to completion, and have time for those important, initial conversations, for those detailed collaborations. There isn’t time to have these conversations on set.

It’s too busy. Often the first relationship, the first collaboration for the director is with the production designer. And it’s such a wonderful time where you can get in the director’s mind, and understand their vision, and ask the questions – because all that has to be disseminated to the entire art department in order for them to undertake their own work. I always encourage producers to try and give that as much time as possible. The production design process and the majority of the work of the art department happens in pre-production. By the time we start shooting, much of that work is done. Certainly there’s no time during the shoot for those key creative collaborations to dig deep and develop ideas.

Construction drawing of the chapel set for “The Invitation”, courtesy of Felicity Abbott.

Kirill: Have you ever thought what you would be doing if you were born 500 years ago?

Felicity: I would be a religious ascetic, a quiet, contemplative – if I had the luxury to do that. Either that, or a cellist. I’ve always played classical music, not professionally, but as a passion since I was young.

Kirill: What keeps you going in this industry?

Felicity: It’s definitely the people and the cultures that I’ve been lucky enough to work in. It’s both a little terrifying and a little daunting to turn up to a completely new country. I worked in Serbia last year, and I’d never been there before. I had no idea what it was going to be like. I had a few Serb friends in Australia, so I knew a little bit about the history and culture of Serbia and former Yugoslavia, but it was such an extraordinary experience.

I was so impressed with my art department crew. There are so many incredible artists that work in the film industry. The majority of my art department crew were fine arts trained or architecture trained. I knew that there are great intellectuals and artists and philosophers in the culture, but it really felt like all of my crew were artists in their own right – which they were. It was a great experience. I was there working on an American film that was set in America, but the great richness of the project was the collaboration with my Serbian crew.

There are things that we were doing on that film that you couldn’t possibly do in America anymore, because either the craft has been lost or it would be too expensive. I had teams of sculptors that had the same training as me, fine arts trained sculptors who we were collaborating with and building some of the sets in my department that were inherently sculptural and required that approach, as opposed to other construction methods. I felt like I was back at art school, sitting in a studio, surrounded by incredible artists, and just such kind and generous people.

It’s encounters like these that make production design so rewarding for me – where you have no idea what lies in front of you, and then suddenly it ends up being this incredibly enriching experience.

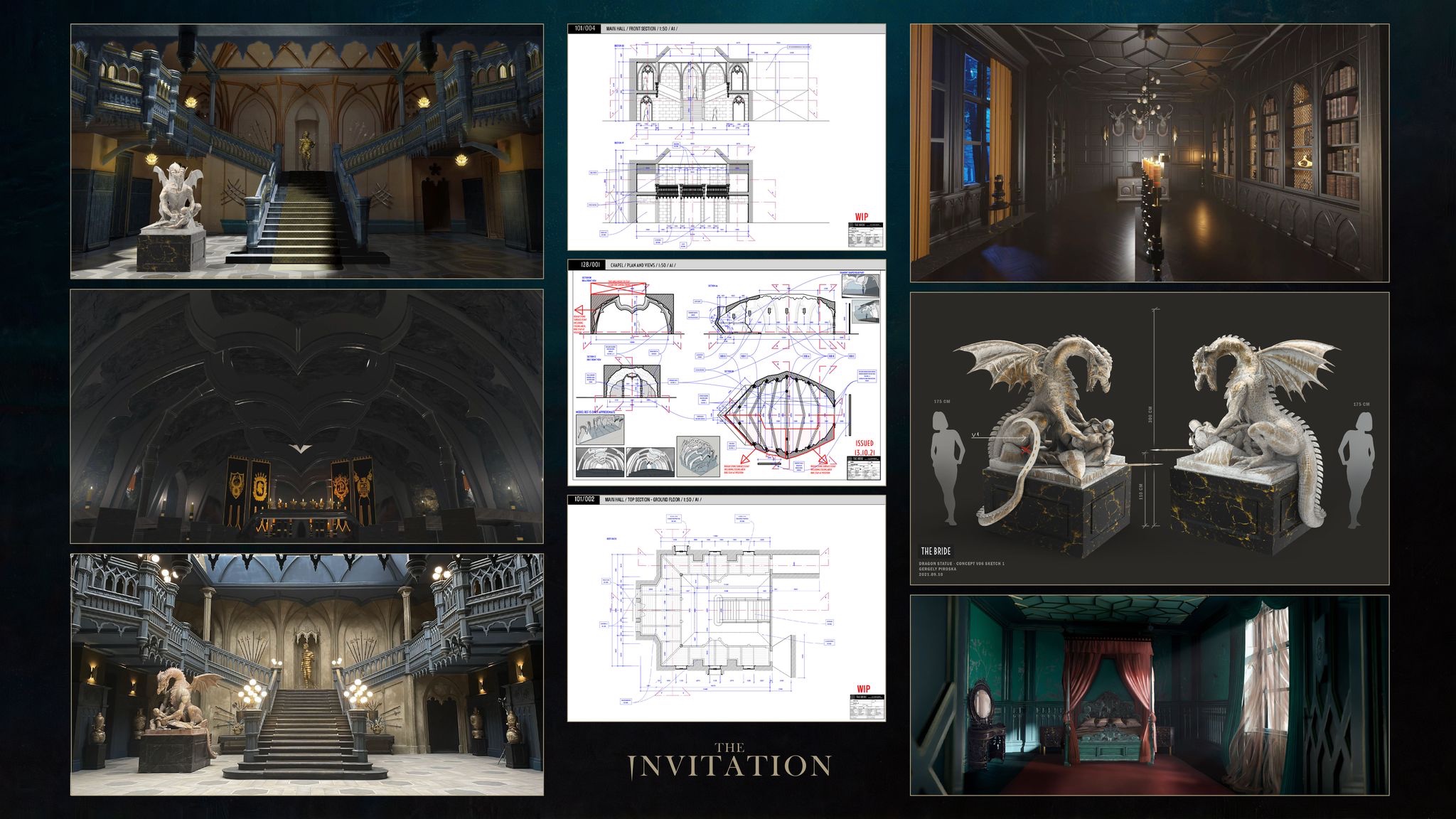

Design process for “The Invitation”, courtesy of Felicity Abbott.

And here I’d like to thank Felicity Abbott for taking the time to talk with me about the art and craft of production design, and for sharing the supporting materials. You can find Felicity online on Instagram. “The Invitation” is available on a variety of digital platforms. Finally, if you want to know more about how films and TV shows are made, click here for additional in-depth interviews in this series.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()