Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my pleasure to welcome Morten Højbjerg. In this interview he talks about how he started in the field of editing, what changed and what didn’t in the transition of editing from physical to digital tools, his approach to “emptying the frame” and keeping the viewer’s attention, and serving as the final bridge between what was shot and what we the viewers see. Around these topics and more, Morten dives deep into what his work on the first two seasons of Amazon’s “Hanna”.

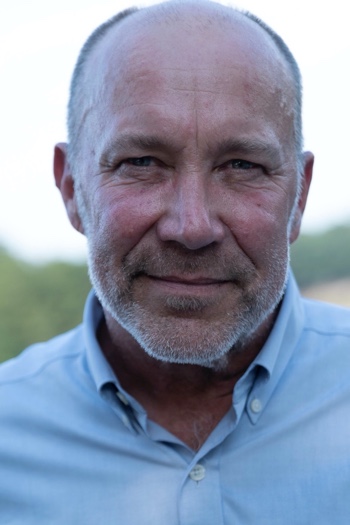

Photo by Bjørn Djupvik

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself, and how early (or maybe late) you knew you wanted to be a part of the visual storytelling field.

Morten: I’m Danish and I grew up in this little village in the countryside. Growing up, I didn’t know anybody who was even remotely in the film industry, so I never imagined that I would have anything to do with movies. It wasn’t even within range of reality. I don’t think it even ever crossed my mind that there was such a thing as editing.

When I was a teenager, I moved to Copenhagen. I didn’t really know what I wanted to do with my life, but by some weird coincidence I got hired as a runner in a production company that made commercials. It happened to be around the time when the whole digital shift was coming, old-school physical editing tables to digital editing, and this company that I was a runner for, invested in one of the first AVIDs in Denmark – which is now one of the most common digital editing systems.

Back then, there was nothing on screens in my life. I didn’t own a computer, I didn’t have a mobile phone. I remember the first time the whole thing was set up and it was playing something, and it just blew my mind to watch video running on this computer screen. It was magic. I had never seen anything like that. It was incredible.

Anyway, they bought one of those, but no one really knew what to actually do with the thing. I was really fascinated, and hating my job as a runner, I started to dig into it. I read the manual, and after doing my runner duties throughout the day, I spent all my evenings learning and studying this fantastic machine. Before long I started being an assistant for some of actual editors. In my free time and on weekends I was cutting stuff on my own, making short films out of all the commercials that were in the archives. Those were random, weird short films out of washing powder commercials cut together with car commercials etc. That was my way in.

As soon as I saw this thing and started to understand a bit about what it was, looking over the editors’ shoulders and understanding the magic of this job, I knew that this was what I was going to do for a living. It was perfect, and I have not done anything else ever since.

Kirill: Looking from the outside in, it was interesting for me to see how reluctant some people were to transition from film to digital. Do you think it was a smooth transition, or were there “pockets of resistance”, so to speak?

Morten: Of course there were pockets of resistance for a while. Editing on Avid is radically different to editing on a Steenbeck table, and I guess it took a few years to change the habits and methods for a lot of people. After my time at the production company I went to the National Danish Filmschool for four years. Back then they still had the old Steenbeck tables standing around collecting dust in the corners. I insisted on using them for my short films, and I made my midterm film on the Steenbeck. It was so complicated, and the whole physicality of it was incredible. You had to be so organised. I spent hours and hours with my head in the bin, trying to find little pieces of film that I had cut out but then later wanted to put back in. On a Steenbeck you needed to think about what you were doing in a completely different way. You needed to have a plan before you started doing anything. It took hours to make changes, with so much looping and rolling the film through the whole thing. I’m really grateful that I arrived at the scene in time to experience that. I think there is a lot to learn from that approach in terms of the thought process that goes in to the editing of a film.

One interesting aspect of editing in digital versus film is that it didn’t actually become faster to cut a feature film than it was back in the day with Steenbeck tables or Moviolas. You might think it would be but it really isn’t.

Kirill: Is it because the art of editing hasn’t changed, and it’s still as challenging to find the right artistic expression? Or maybe is it because you have more digital material to work with because the camera keeps on rolling?

Morten: I think it’s a combination. The fact that you can roll now gives us much more material to work with than what it used to be when it was like a 35mm camera. With film, when you pushed the “On” button, you could hear the money roll out of it [laughs] – and now it’s not a big thing anymore. You record to a card and then reuse it

But another thing is that the thought process has not changed. That still takes a certain amount of time from when you see the material the first time, regardless of how much there is. You take that material on a journey to a finished film. It’s still a physical journey, but it’s also a mental journey and that takes a certain amount of time before you can conclude it.

Somehow I also think there is a danger in digital editing actually. Because it’s so easy and you can make endless copies and versions effortlessly, it has become easier not to properly think about what you are doing. It has become easier to get lost.

Kirill: On a more technical side of things, how obsessed or perhaps paranoid are you about losing material on those digital cards or disks? Is there more fragility to it compared to the old days of film?

Morten: That is true, but it’s always been like that on film as well. If the assistant did something wrong and exposed it to light, it was gone. Back in the film days, you would go to the lab after the end of the daily shoot, and lock the film roll into a special closet with all sorts of codes and keys. Whatever it is, a film roll or a flash card, it often represents a huge amount of money. A whole day of production that you may not able to replicate if it’s gone.

Kirill: Do you think there’s ever going to be such a time as a disc big enough that it doesn’t need to be bigger?

Morten: It doesn’t look like that, does it? The resolution keeps going up, from 6K to 8K to now 12K. The drives needs to be bigger, and then everything grows simultaneously all the time. I don’t know if there will ever be a time when we can’t really tell the difference. Is it 50K? Is it 72K? I don’t know if the human eye has any limit like that.

That’s the thing about film, and why so many people maybe still love film. It’s a more organic thing. It’s not limited in these numbers. It’s a fluent thing that is, maybe, a better replication of how we work as organic beings.

Editing of “Hanna” by Morten Højbjerg, courtesy of Amazon Studios.

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my delight to welcome Matthew Ferguson. In this interview he talks about how much preparation and attention to detail goes into every single shot, the fast-moving pace of productions, the importance of research, and what keeps him going. Around these topics and more, Matthew dives deep into what went into creating the sumptuously luxuriant worlds of Netflix’s limited series “Hollywood”.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and when did you know that you wanted to be part of this creative field.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and when did you know that you wanted to be part of this creative field.

Matthew: My love of film started when I was 8 years old. I saw a film on TV called “The Snake Pit” with Olivia de Havilland from 1948. It was a film about a woman who finds herself in an insane asylum. There was a particular scene when the main character is sent to the ward for the severe mental cases. She stands there surrounded by mentally ill patients walking aimlessly around her and the camera starts to pull up. As it does, we start to see the walls are made of dirt and suddenly we are no longer looking down on people but rather snakes withering around in a pit. That moment made a big impact on me. I was on the edge of my seat and I wasn’t exactly sure what it was that moved me, but I knew I had to figure it out.

So, from then on, I was on a journey to learn as much about film as I could. There was no internet, and I would ask my parents take me to the library, and thankfully they indulged me. I would go to the film section and read about movies, and watch them whenever and wherever I could find them, and absorb as much as I could. It was then that I knew I wanted to work in film production.

When I was 10 years old, my parents gave me a Super 8 camera for Christmas. I started making movies with neighbors and friends, and then would screen them a week or two later because they had to be developed at the local Kodak Camera shop and it generally took a week to get the film back. At this early age, and thanks to support from my parents and friends there was no question that I wanted to work in the film business.

Kirill: Being in the industry now, and learning back then about how these stories are told, does it diminish your own experience as a viewer when you watch productions that others work on?

Matthew: When I’m watching a film that’s well done, all it does is enhance my passion for the viewing experience. When the craftsmanship is excellent, it just makes it that much better for me as the viewer, because I have an understanding of all the hard work that goes into it. It doesn’t take me out of it. I may be aware of what they’re doing, aware of the edit or the camera angle, but it just makes me enjoy it that much more and it will stay with me. Conversely, only when it’s poorly done is the experience diminished.

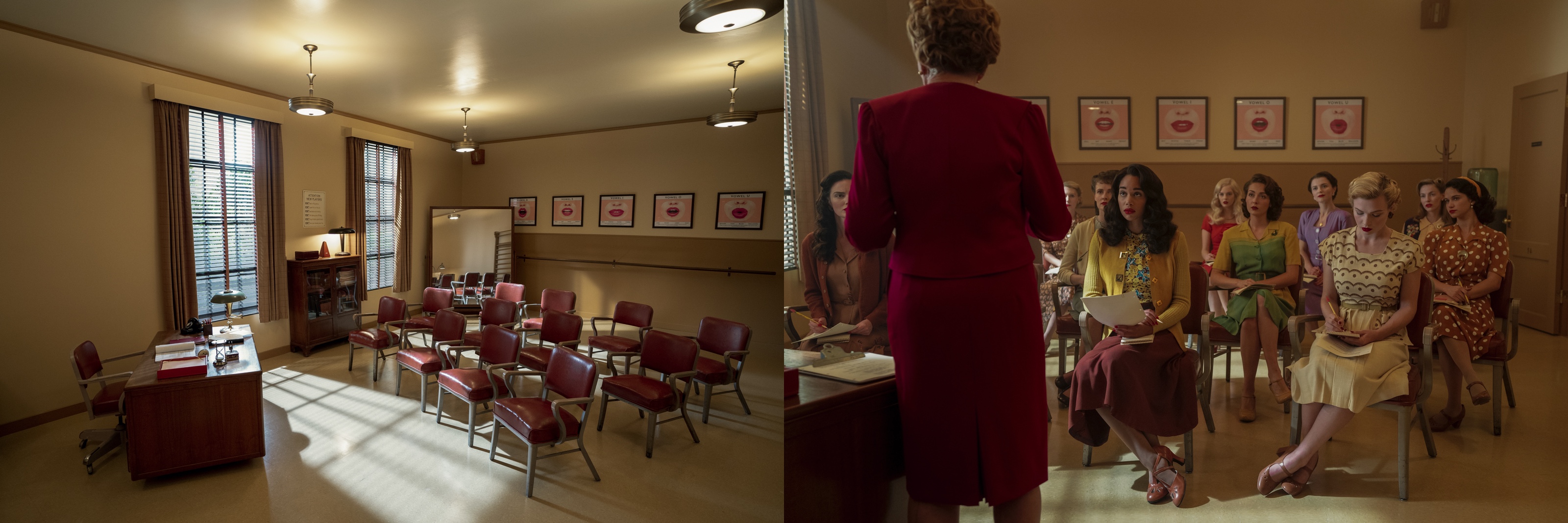

Production design of “Hollywood” by Matthew Ferguson, Ace Studios make-up suite. Courtesy of Netflix.

Kirill: How was your transition from reading about how these productions are made into being on set? Do you remember if there was anything particularly surprising or unexpected to be surrounded by all the moving parts of a real production?

Matthew: Yes. How technical the whole process can be. I started out as a PA in production getting as much experience as I could, and then slowly working my way up in the Art department. From time to time, there would be moments, whether lining up a shot or talking about a stunt and I’d find myself almost stepping out of the work and thinking “this is exciting, I’m actually part of it now.” Imagining, and then being a part of Hollywood, has always been a thrill for me and I love it.

From a more practical standpoint, I realized early how technical the process was. It might look seamless and spontaneous, but it’s all laid out and planned before shooting. This is when imagination and fascination meet practice, and I find that interesting and challenging as well.

Kirill: When you talk about what you do with people who are not in the industry, is it difficult to convey the different aspects of it?

Matthew: Not so much, and it helps that I live in San Francisco and Mendocino, both in Northern California, and of course I work in Hollywood. In other words, I am accustomed to being the simultaneous translator between these two distinct worlds of Los Angeles and San Francisco.

Kirill: Moving a little bit closer to “Hollywood”, but also in general, what are your thoughts about where the visual storytelling is taking place these days? It feels to me as a viewer that a lot of mid-budget dramatic storytelling has migrated away from the feature films and into the world of these episodic productions.

Matthew: A lot of it is in episodic productions and there’s so much wonderful content that’s now streaming on Netflix, Amazon and Hulu for example. I find many of these shows quite interesting. The films that I am attracted to are generally not big blockbuster movies and the films/shows that I want to be a part of are more character-driven and story-driven, and not big sci-fi or action movies. Not that those aren’t great movies. They’re fun and escapist, but that’s not something that appeals to me at the moment.

Production design of “Hollywood” by Matthew Ferguson, Ace Studios starlet classroom. Courtesy of Netflix.

Kirill: In case of “Hollywood”, does it help that as the production designer, you worked on all the episodes with the same cinematographer, the same art director, the same costume designer – to keep the visual continuity for me as a viewer?

Matthew: Absolutely, no doubt. When you work on these shows, at times you’re moving very fast and schedules can change. In the end, you hope to have a completed project that is visually cohesive. So, having the same crew with the relationships, communication and trust, helps to stay on top of it. And it certainly doesn’t hurt that they are all very talented and nice people to work with.

Kirill: Taking a step back, how did you find the show, or perhaps how did the show find you?

Matthew: I worked as a set decorator for many years. One of the movies that I decorated early on was “Running with Scissors”, which Ryan Murphy directed. I met him on that project, and then I worked on a pilot with him that ended up not getting picked up. And years later I worked on “American Crime Story: Assassination of Gianni Versace”, and then from that we were did another Netflix show called “Ratched” which is scheduled to launch later this fall. I was working on that as the decorator with the designer Judy Becker whom I’ve worked with over the years. She had to leave the show to go into another project. At that point I took over and production designed the last three episodes of “Ratched” – and that’s when Ryan asked me to do “Hollywood”. Once we wrapped “Ratched”, I had a week off and then we started prep on “Hollywood”.

Kirill: One interesting aspect of this show is that half of it is based on real people and real events, and the other half is more of a what could have been or what should have been, almost projecting the social outlook of 2020 back in time to when the events are happening. As you were exploring the design language of the show, how did you approach reflecting the balance between these two worlds?

Matthew: I really wanted to bring historical context to the show, to help inspire the characters and the stories. For example, Ace Studios is a hybrid of RKO and Paramount. The studio system back in the golden age was a very real thing. There were five major studios that dominated the film industry, and everything was within the walls of those studios to make a film. You had contract players, the directors, the acting classroom, the commissaries, the stages, the editing rooms. As we were working on Ace Studios, we built all of that on stage.

We knew that the commissary was going to be a big permanent set with a lot of scenes in it. I started to research what the studio commissaries looked like back in the ’40s. I looked at Warner Bros, Paramount and RKO, and decided to model our commissary after the Paramount commissary. My set decorator Melissa Licht had the tall task of trying to find a hundred period chairs to go around the tables. One day she came up and showed me a picture of a chair that she’d found. I realized it was an exact chair from the Warner Bros commissary from the 1940s. In my office, I had pictures of Errol Flynn and Betty Davis sitting in the chairs. I also had a deal with Getty Images and had all the Kodachrome movie star portraits line the walls. When the set was dressed and ready to shoot, it felt like we were back in the Paramount commissary.

Production design of “Hollywood” by Matthew Ferguson, Ace Studios commissary. Courtesy of Netflix.

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my pleasure to welcome David Bomba. In this interview he talks about the first three decades of his career, the importance of research and realism in creating the worlds for his stories, the changes he’s seeing in the world of episodic storytelling, and the collaborative nature of this field.. Around these topics and more, David dives deep into taking over the third season of the hit Netflix show “Ozark”.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

David: My name is David Bomba and I am a production designer on the third season of “Ozark”. I’ve been in this business since I graduated from college. I studied architecture at Texas A&M graduating with a bachelor’s degree in environmental design, and when I graduated, within months I moved to Los Angeles to pursue a career in production design in film.

My mentor was George Jenkins who was an Academy award-winning production designer. He did many films for Alan Pakula – “Sophie’s choice”, “Klute”, “Presumed Innocent”. He won the Academy award for “All the President’s Men”. He was one of my last phone calls on a long list of names that I wanted to contact upon arriving in California. I didn’t know anyone in Los Angeles. I didn’t know anybody in the industry, and I just knew that I wanted to pursue design. George allowed me to audit his production design class at UCLA. He and his wife Phyllis became good friends of mine, and his teaching and support was what kept me in Los Angeles in those early years where I was trying to get any door to open up.

What George emphasized was research and realism in design. Whether his films were period or contemporary, he did extensive research. Back then we were using Polaroids and film when gathering information and researching the old-fashioned way. When you scout, you go into a house and you look at something. For instance, my job on “Ozark” this season was to build the casino and to develop the Missouri Belle. I was familiar with offshore gambling facilities, as I grew up in New Orleans. I knew riverboat or barge style gambling where all of the gaming is on the water – that’s the restriction for gambling in certain states that the actual gaming has to be on the water. They use boats or barges, and the casinos are built on the water.

That’s what we were presenting on “Ozark” on Lake of the Ozarks in Missouri – a floating casino. So I went and researched several different gambling facilities. One of them was in Indiana on the Ohio River, and then I drove with Wes Hagan, the location manager, down to Caruthersville, Missouri and saw another one. We ended up in Memphis where I dropped Wes off, and then went further down into Mississippi to Tunica to see a couple of casinos there. The casino was the key design challenge for me and was one of the reasons that I actually took the job.

Production design of “Ozark” Season 3 by David Bomba, Byrde Foundation gala. Courtesy of Netflix.

Kirill: If you look at the changes that the art department has seen in the last 30 years from the technical perspective, what do you think has been the biggest change?

David: One of the things that is different is the amount of prep time. It seems with many projects that the amount of time that you have to gather information and to develop ideas is becoming shorter. I just remember having more time in the early part of my career.

Speaking of technical differences, back when I started, we were shooting on film. Different types of film stock reacted differently to color, surface, pattern and texture. You tended to have more of a dialogue with cinematographers in developing these aspects of design. For instance, they might choose a particular film stock for night because it holds on to the solid blues or the blacks.

For me there’s been a big difference between film and digital. Digital quality keeps changing and getting better and there are ways to tune things in a different manner. The lighting challenge on the interior of the casino on “Ozark” was different from any other job that I’ve ever experienced.

“Ozark” is the first episodic production that I’ve done where in ten episodes, there were multiple directors and cinematographers. You’re dealing with different personalities, how they work and what they like and dislike. As an artist, you are drawn to certain things and you gravitate towards certain things. What impressed me especially was working with Jason Bateman who is acting, directing and producing the show. He was going to direct the first block or first two episodes. As an executive producer, he had a lot of say on what the entire season was going to be.

Jason and I had an early conversation about tone and color and palette. Then Ben Kutchins and Armando Salas, the cinematographers, came in with their ideas of color and palette. Armando, in particular, was somewhat reticent to go into the reds and golds that I wanted to introduce into the Missouri Belle. It was not the blue-gray look that the show was known for. It wasn’t shadowy or watery. It was a different palette, but Jason specifically wanted to step outside of the lines of that palette and the look that had been established. That was another reason why I came into this third season. The show had established a certain look in the first two seasons, but in conversations with Jason and the showrunner, Chris Mundy, I was assured that I was going to have an opportunity to expand the look of the show- and that proved to be true.

We expanded the palette in this season, and we really opened up some the texture and the scope of the show. It was with the Missouri Belle casino and compound, as well as revealing a whole other world with Omar Navarro’s hacienda in Mexico. We introduced him and his environs, and that was another exciting challenge that I was given.

Another thing that is different on an episodic production is that you don’t have the opportunity for an extensive dialog with your director. I’m used to doing features where the collaboration lets you develop and expand a vocabulary, and it’s different in episodic. I got to do that somewhat with Ben during prep. Armando came in towards the end of the initial prep period to engage with the casino and the set that we were building for that. But overall, the prep dynamic was quite different for me.

Production design of “Ozark” Season 3 by David Bomba, REO Speedwagon concert. Courtesy of Netflix.

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my pleasure to welcome John Paino. In this interview, she talks about changes in the way stories are made in movies and television over the last few decades, the ever-raising quality and expectations bar from the viewers, what captures the audience’s attention, and what stays with him after a production is over. In between all these and more, John dives deep into his work on “Sharp Objects”, “Big Little Lies” and “The Morning Show”.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself, and how early you knew that you wanted to be in this field.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself, and how early you knew that you wanted to be in this field.

John: Going to a movie theater is magical, and I would go whenever I could. I actually was more inclined to be a fine artist, and I went to school for cartooning in New York in the early ’70s. I found that cartoonists are the worst teachers in the world. They sit at their desks and they’re so into their inner life. They’re not good communicators. So I gravitated to the fine arts department at the School of Visual Arts.

Once a week I’d go to St. Marks movie theater and watch “Blade Runner”, so I was always intrigued by that world. After I graduated from the art school with a degree in fine art, I got kind of tired of the whole New York art scene. One day I happened to wander into a theater and just volunteered, starting building and painting sets. It was in the off-off-off-Broadway theater world. Then, slowly, some people who were in theater started doing music videos in the ’80s. Then I started designing sets and doing production design for music videos and commercials. And then some of those people started doing films.

That lead me to working on low budget indie movies in the early ’80s in New York, and that’s how I segway’d into film design. That’s been my path into this field.

Production design of “The Morning Show” by John Paino.

Kirill: If I had a time machine, and I could bring the young you from the ’70s / ’80s all the way into 2020, would you say that the overall structure of the art department of these productions would still be recognizable?

John: I think they still would in the art department. We still have to physically make things. We still have to design them.

Sure, the computer technology has shortened some work times. But there’s also the human factor. Directors, for the most part, still want to walk in a set. They want to see it. They want to look at the reference you’re putting together. My big thing when I design is making mood boards that convey atmosphere. With those images, you still want to go get those out of magazines. If I can, I still go to the New York public library’s picture collection and pull swatches from there.

I still have bags of fabric. The art department still has bags of fabric and pictures from old newspapers. Computers certainly have shortened some work as far as getting from point A to B in certain respects. But people still have a tactile need. I have to carry this stuff around from place to place, and I wish everything was digitized. I wish I could have someone digitizing all my art books 24/7 [laughs].

There’s still a physical aspect to designing movies, seeing things built, and the director walking into an office and seeing all kinds of stuff laying around – tile, samples of wood, etc. I don’t think that aspect of it will ever change.

Production design of “Sharp Objects” by John Paino.

Kirill: Is there something that is feasible to do today technically or maybe economically that wasn’t as achievable – or not achievable at all – 20 years ago?

John: I used to do a lot of high-end commercials. Let’s say you go back 20 years ago, and you wanted to have daisy petals come out of a flower and then fall on the ground over and over again. I had incredible prop makers who were able to build a physical flower that had a cable running through it where pedals would come out of it and then drop to the ground and then be resettable. That was expensive and a lot of times commercials would not do those things, because they were just too expensive.

The other day I saw a commercial where someone is in a nondescript office and their computer starts spitting out shredded paper by the thousands, and it fills up a room. Only the biggest clients would be able to do that physically, and I worked for high-end clients that would go for it. We would do it physically, and that was really interesting and challenging. You’d have to have really skilled people to be able to do it and then reset it. You’d have to think about it more.

Now it would be achieved with CGI. I’m not saying you don’t think about it as much, but there’s something lost when you’re not as involved with it and it gets subbed to someone else who will be creating it. From the economical standpoint, you can do all that a lot cheaper, and people are doing it more and more, not just in commercials.

The flip side of that is that people who are trying to do a million dollar movie have at their disposal these incredible visual effects to achieve things that were simply not available to me back in the ’80s when I was working on indies. That’s a positive thing to have people being able to do that. These are the two sides of technology in film.

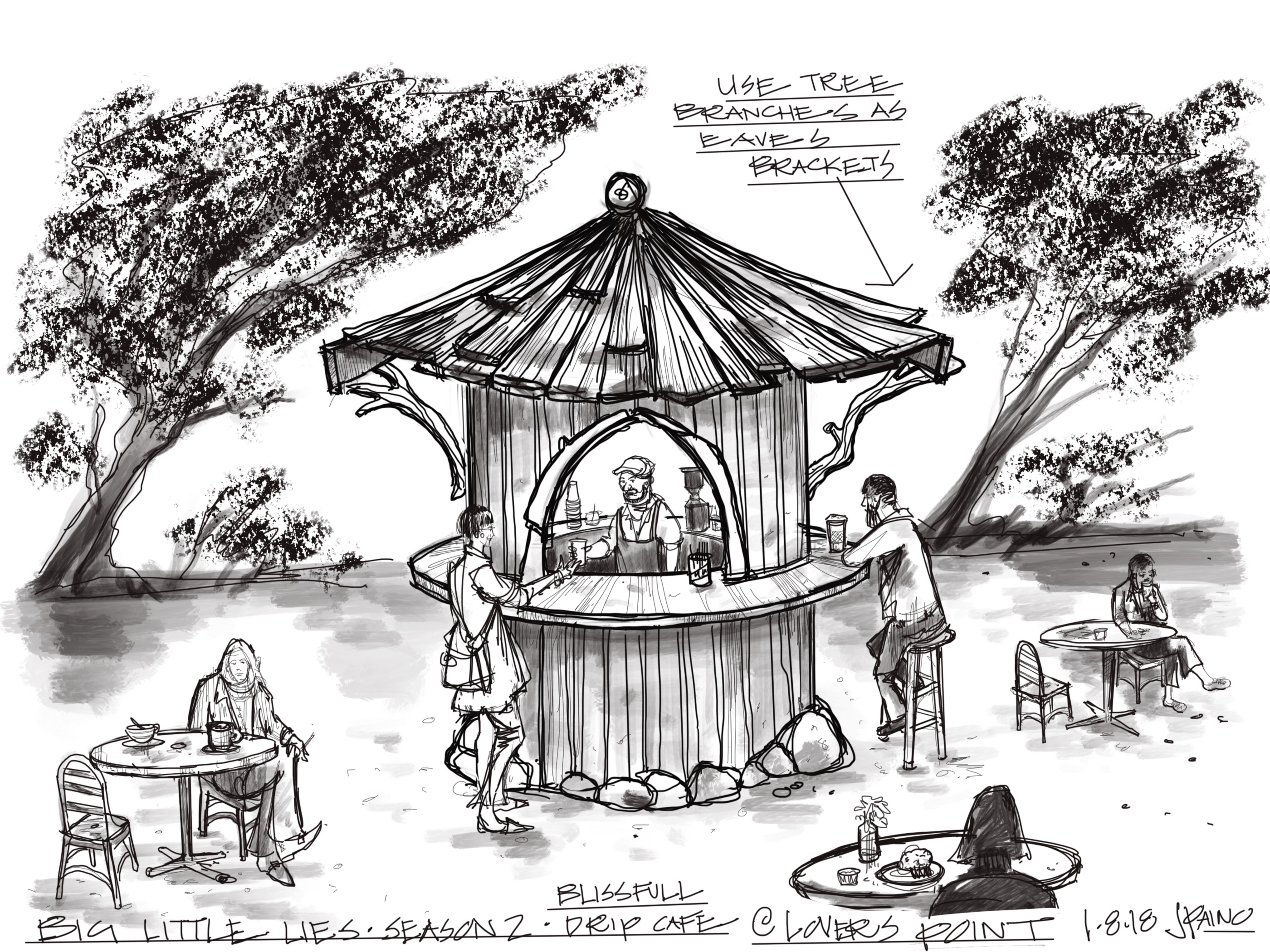

Sketches for “Big Little Lies”, courtesy of John Paino.

Continue reading »

![]()

![]()