Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my pleasure to welcome Toni Barton. In this interview, she talks about what she sees as the biggest change in this industry in the last 25 years, her approach to creating the worlds for her stories, building layered sets that reflect the history of the place and the characters, how she sees generative AI, and what keeps her going. Between all these and more, Toni dives deep into her work on “Fight Night: The Million Dollar Heist”.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Toni: From a very young age I had a fascination with architecture – and was very excited when my cousin introduced me to her youngest brother in law, Julius Haley, who was the first architect I would meet. A few years later while on summer break, my mother directed a children’s theater production of the musical “The Boy Friend”. She enlisted my sister and I to paint all the sets. I did not know what I was doing, but this experience planted a seed. That seed grew in high school, where I took many drafting classes and eventually interned at an architecture firm.

With the sole purpose of becoming an architect I attended the University of Southern California, but that singular focus broadened quickly. Songfest was an annual fundraiser held by students at the Shrine Auditorium. While practicing with the Black Student Union, someone asked if I could design our backdrop. So, in the middle of the night I was painting a large backdrop on top of the parking structure. Once again, I didn’t know what I was doing, but I was having fun. Over those years I learned more about architecture, designed more plays and musicals, worked in the scene shop, and designed several short films. After graduation, I moved to New York and studied scenery for stage and film at NYU. For a few years I assisted several Broadway set designers and worked at a couple of industrial set design firms – and once I was accepted into the union, I started working in film.

I was an assistant art director for many years, drafting, learning while crying and trying to figure it out [laughs]. I worked with some amazing people, including art director Patricia Woodbridge. She brought me on “Mona Lisa Smile”, “Hitch”, “Freedomland”, “Sherlock Holmes” and “The Bounty Hunter”. She taught me what to do as an assistant art director and put me in places to learn. Patricia was my film mom, and I will forever be grateful for her. Later, I started art directing on a lot of different TV shows, and eventually collaborated with the production designer Loren Weeks. He was hired to design the first seasons of the Marvel Netflix series “Daredevil”, “Jessica Jones”, “Luke Cage”, “Iron Fist”, and “The Defenders”. After that, as a good boss does, he pushed me out of the nest, saying “Now go fly and design”, which was scary, but wonderful. All of this thankfully lead to production designing “Fight Night: The Million Dollar Heist”.

Toni Barton and the art department of “Fight Night”. Courtesy of Toni Barton.

Kirill: Looking back at the first 25 years of your career, what do you see as the biggest changes in this field?

Toni: The biggest change for me is how we consume media. When I was growing up, the entire family would sit down and watch a show, whatever was on. There were 4 or 5 channels, and everybody would want to have that water cooler moment the next day. You didn’t want to come in the next morning without seeing what happened on your show the night before, because everybody would want to talk about it together.

Now, everybody is in their private space – watching it live or for the fiftieth time on their phones or three seconds after it’s left the movie theater and is streaming.

My preference for episodic shows is to drop weekly – giving the audience a chance to breath with the story and to anticipate what’s going to happen the next week. I like that much more than digesting content all at once.

Toni Barton and Lance Totten, the set decorator of “Fight Night”, on the set. Courtesy of Toni Barton.

Kirill: From design perspective, did you start designing on paper, or was it already in the world of digital devices and tools?

Toni: When I was in architecture school I mainly drew by hand, not learning much on the computer until later when my studio professor told us “I don’t want anybody to think of AutoCAD as the designer. It is merely a tool. It is no different than using a pencil on vellum or ink on mylar”. Realistically, when I was an assistant art director drafting sets, I drafted only on the computer. But as a designer, I think with my hand. When I’m designing a set, a lot of times I’m on my drafting table. I’m figuring it out with a pencil, trace paper and a scale ruler. I’m constantly moving the pencil, sketching through ideas, or tearing off a piece of trace and taping it on top of another to develop my ideas from concept to reality.

At a certain point, I may hand off a sketch to my set designer. And sometimes they give it back digitally so I can modify my ideas in AutoCAD, thinking through the details. Designers use all sorts of tools today for 2D and 3D modeling. These tools might be on a computer or iPad. It might be the set designer or the illustrator making a 3D model or fly-through animation. It’s just the tools that we utilize to tell the story, but they’re not designing it. They are simply how we communicate our ideas.

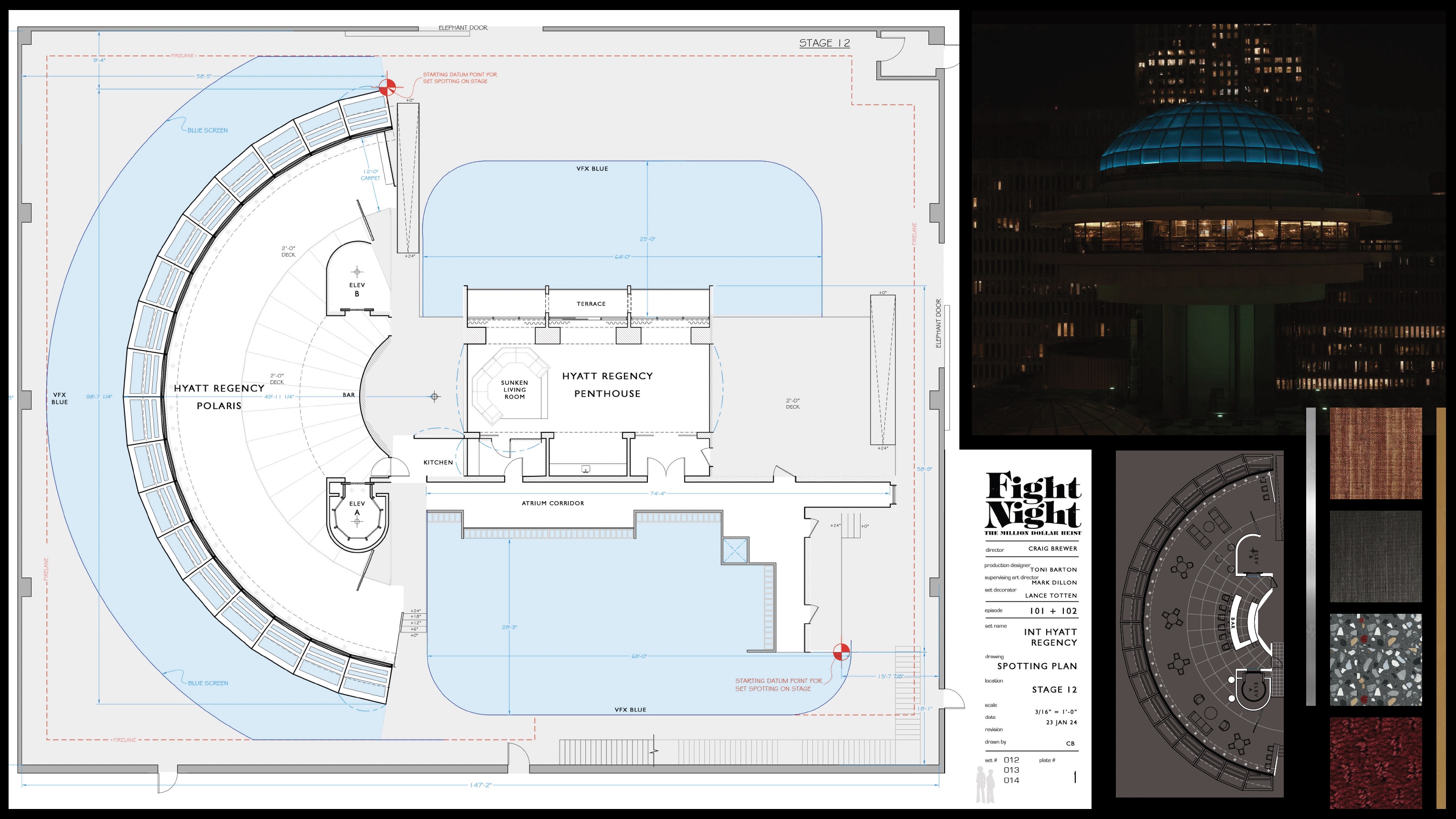

Floor plan and materials for the Hyatt Regency set of “Fight Night”. Courtesy of Toni Barton.

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my pleasure to welcome Christophe Nuyens. In this interview, he talks about the transition of this creative field from film to digital, bridging the gap between feature films and episodic productions, learning from different cultures, and what advice he’d give to his younger self. Between all these and more, Christophe dives deep into his work on the second season of “Andor”.

Christophe Nuyens on the set of “Andor”. Courtesy of Lucasfilm/Disney+.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Christophe: I finished a trade school as a general electrician, but I wanted to do something more, and I went to film school. During your first year you can choose between editing, sound and image – which is light and camera. So we had our first workshop, and I had the camera in my hands, and I knew this was it. I really loved the mix of technical and creative.

Kirill: Do you feel that you can teach the technical part, but the artistic part comes from within a person, and if one doesn’t have it, it can’t be learned?

Christophe: No, I think you can teach both. When I was growing up, I didn’t have a lot of cultural influences in my life, at home or at school. It is something that I grew over the years. When I started at the film school, I noticed that I needed to catch up on it. I spent a lot of evenings around that time watching movies with my friends, and it grew on me.

You can cultivate it the same way you cultivate the technical skills. There are also people who are more artistic than technical. Maybe I am more naturally inclined to be better at the technical side, but I grew and worked on my creative side over the years. I really believe you can grow the creative part of your brain.

Kirill: Is there such a thing as universally good art vs universally bad art, or is it all subjective?

Christophe: It’s subjective. There’s so many forms and styles of art. And that is good, because there’s something for everybody. Everything can be art, and people with different taste can find things that they appreciate.

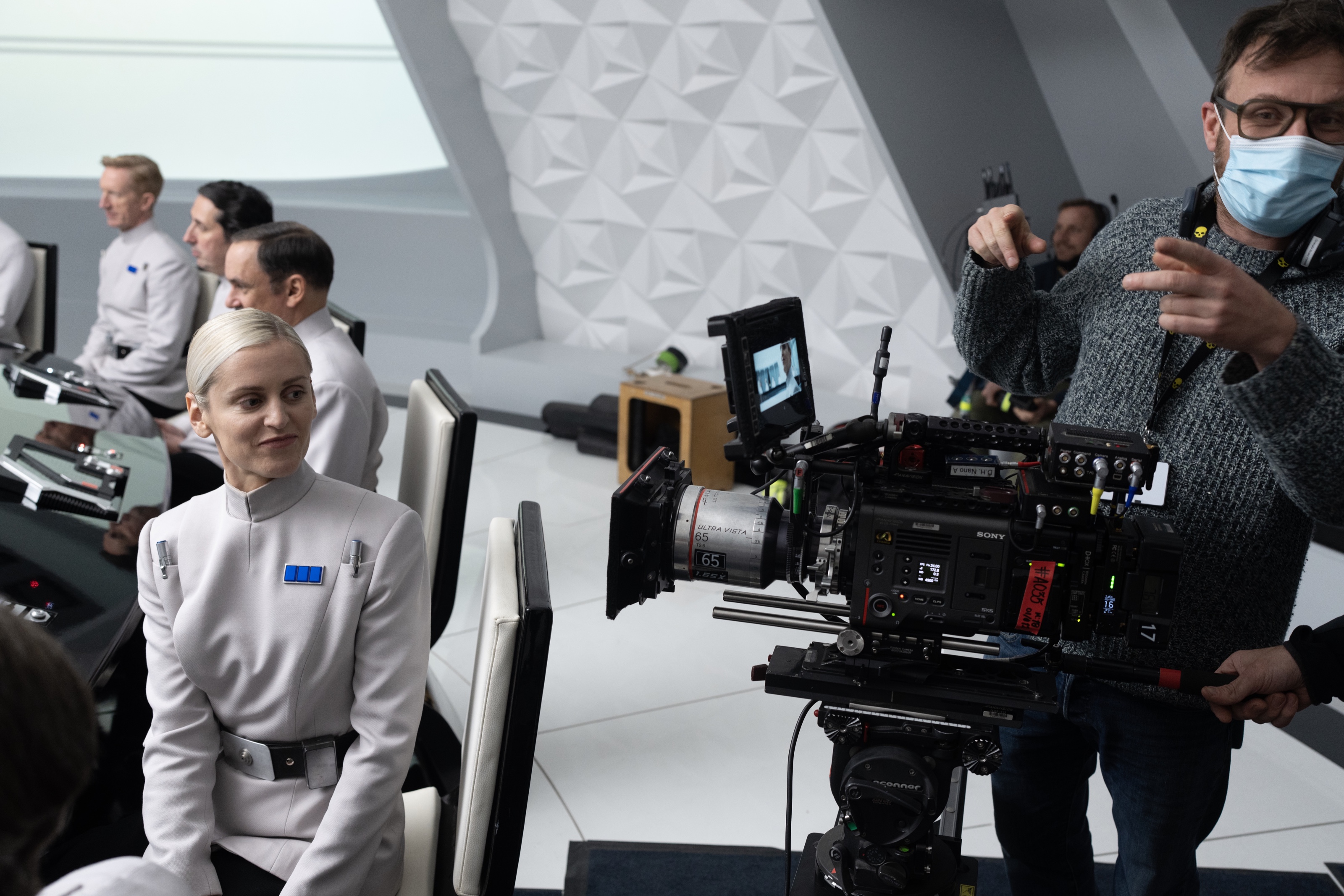

Christophe Nuyens on the set of “Andor”. Courtesy of Lucasfilm/Disney+.

Kirill: Was film still a thing when you were in film school?

Christophe: We did most of our projects on 16mm, either Bolex or Arriflex SR2. We did a few things on video, but it was really basic at the time. I remember those assignments to film something and edit it ourselves, and it was a nightmare. The computers were slow, the Video cards didn’t work, the software was basic. It’s incredible to see how all of that progressed since then. These days I teach at that same school, and the difference is night and day. They can edit it in DaVinci, they can grade it, and it’s so accessible. Sometimes I’m a bit jealous to see that [laughs].

Kirill: How was the transition from film to digital for you after you finished the film school?

Christophe: When I graduated, most of the productions were still on film. I was exposed to both mediums, and I’m happy about it. I know how to light for film. I still have an analog still camera, and I use it a lot.

But at the same time, I’m so happy that the digital revolution happened. It’s a bigger toolbox for your creativity, especially for night scenes. It’s much easier to light something natural, and to do something with less. I started my career in Belgium, and it’s a smaller market with smaller budgets for TV shows and films – but you still want to make good things. I did a TV show called “Cordon” about 10 years ago. It was an ambitious project for its small budget, and that project started my international career. I don’t think it would have been possible to make that project on film. We had a lot of night scenes on it, and it’s so much different to light a night scene on a digital camera.

Cinematography of “Andor” by Christophe Nuyens. Courtesy of Lucasfilm/Disney+.

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my pleasure to welcome Julian R. Wagner. In this interview, he talks about what is art, how this creative field adapts to technological changes – transition to digital, visual effects and generative AI, how he approaches designing his movies, and what keeps him going. Between all these and more, Adam dives deep into what went into making “September 5”.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Julian: My name is Julian Wagner, born in Germany but would describe myself rather European than German. I am a Berlin based Production Designer, working mainly for film and television.

I was interested in art and architecture very early on. My father has been an architect and that certainly had a strong influence on me. When I was 13, I started acting on 2 Series and some years later as well for the Theater. Those years had a strong influence on my path, because my passion for narration and film in particular was born. During my short time at the theatre, I then realised that I would rather step behind the stage and camera to be able to create more myself. I was so fascinated by telling stories in a visual way and combining my interest in visual art and narratives. I was trying to bring both together, but it took quite a long time to find the right path.

I left movies for a while, and I became a photographer, mostly for fashion and beauty. Then I decided to study design and art in Italy, and I shifted the focus back to the creation of spaces and other forms. During these studies, I focused on Graphics and Media, and directed my first Music Videos. After completing my degree, I worked mostly on music videos and commercials for smaller companies. And at some point, a cinematographer I was working with on a music video asked me if I could do production design on his first short film. It was an appealing prospect, as I realized that I could take all the skills I had – designing, art, photography – and combine them with the way I told stories through music videos. From that moment on, I knew that I wanted to do production design on movies. I went back to the film academy in Ludwigsburg and studied production design.

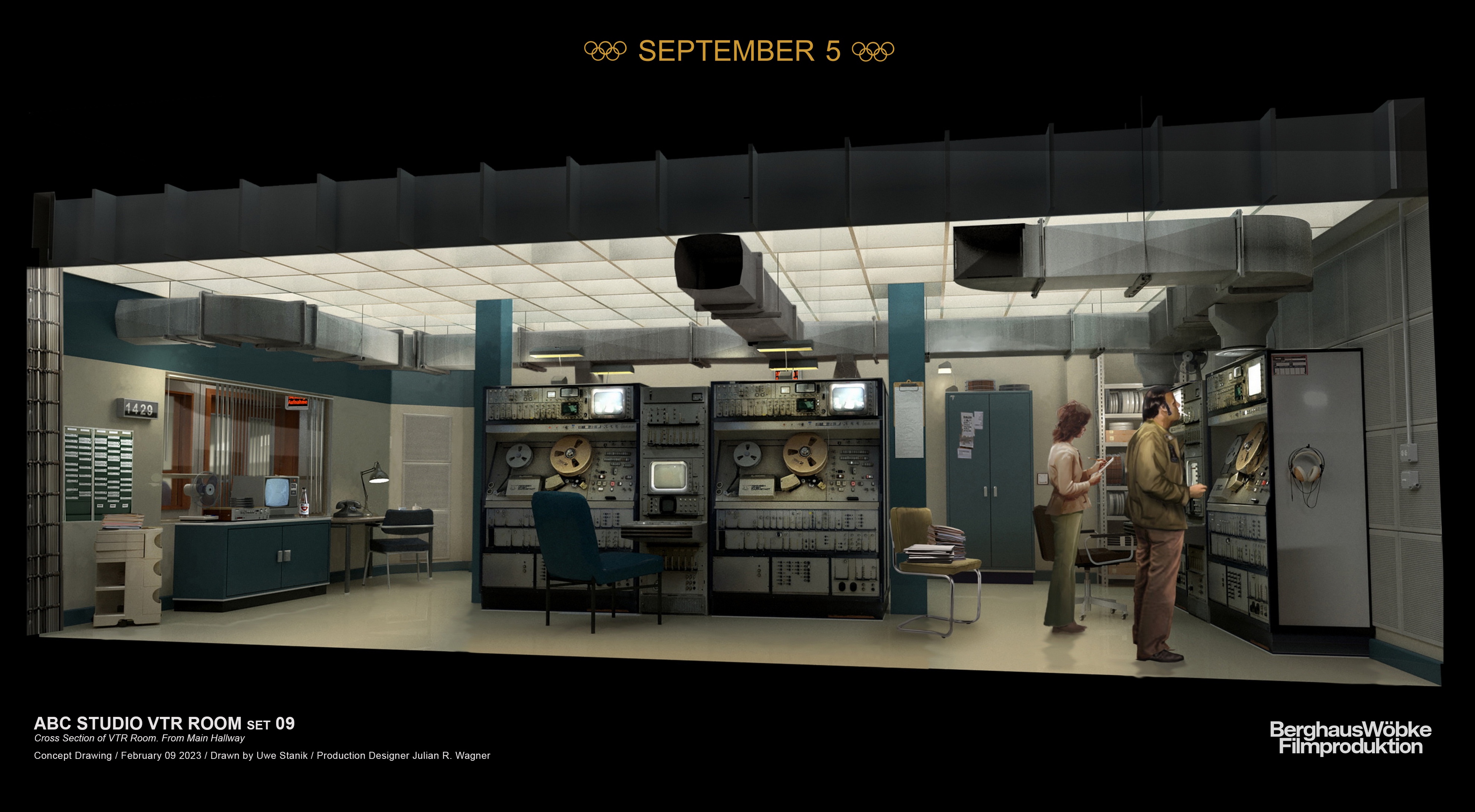

Concept art for the Vault-Type Room for “September 5”. Courtesy of Julian R. Wagner / Paramount Pictures.

Kirill: What is art? Is there such a thing as objectively good and bad art, or is it all subjective?

Julian: It’s an interesting question because everyone would answer this a bit differently. It also feels like the most fundamental question of all time if you’re studying art. You could also ask whether something in art is right or wrong.

Some argue that there are objective standards for evaluating art. Like for example technical skills – the artist’s mastery of technique and materials. From this perspective, we could also talk about composition or the use of visual elements such as balance, contrast and harmony. We could say this works and that doesn’t work. But isn’t that also a subjective view? We could talk about innovation. Is it something original? Or just an interpretation or a new edition of an existing work of art? We could talk about the emotional impact – the ability to evoke strong feelings or thoughts.

Taking these viewpoints, good art adheres to all those criteria, while bad art falls a bit short. But this is just one perspective.

The other perspective, and I find myself much more strongly in this one, sees art as something entirely subjective. I base the judgment of good and bad art on individual taste, cultural background, and the experiences you have had. In this view, the value of art lies in its ability to resonate with its audience, making the distinction between good and bad relative.

I see art not only as subjective but even more as a reflection of life itself. For me, it’s all about life, and this is what I bring as my contribution. I contribute my experiences in my life and how I see things, with all the struggles and joys. For me, art is deeply personal. The so-called objective criteria do not work for me and my understanding of art.

Ultimately, whether art is good or bad may also come down to the relationship between the work of an artist and the audience or the viewers. It is all about the relationship that we are building, especially in this art form of filmmaking.

Concept art for the parking lot for “September 5”. Courtesy of Julian R. Wagner / Paramount Pictures.

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my honor to welcome Eliot Rockett. In this interview, he talks about the transition of the industry from film to digital, advances in lighting technology, potential impact of generative AI, and working through the Covid times. Between all these and more, Eliot dives deep into what went into making the breakaway horror trilogy of “X”, “Pearl” and “Maxxxine”, its message of self-destructive pursuit of celebrity and fame, the cathartic experience of the horror genre, placing each movie in its own time but connecting them all, and how “Pearl” might have been a ’40s film noir instead of a full blown Technicolor extravaganza.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Eliot: When I was an undergraduate at the University of Oregon, I was working at a little movie theater called The Bijou in Eugene. I ended up taking a class in the film studies department, almost randomly, and our professor Carl Bybee started showing us all these movies from the French New Wave and the New German cinema. His approach was that film is art and social criticism, and not entertainment. That struck me at the time, with the combination of working at the theater, seeing the movies that we were showing at the theater at the time, which were in the similar vein.

This class that I took started the wheels turning, and after I finished my undergraduate degree in philosophy, I went to graduate school at NYU for film. At that point, I was thinking I would probably try to be a director. But what happened was that everybody in the program needed to use people in the program to shoot their student films. Generally what would happen every year was two or three people would end up shooting everybody’s movies, because they were the people that had a propensity for it, and that was the one crew position that could screw up the entire movie.

I had done tons of still photography prior to that while I was in undergraduate. I would have probably gotten a minor in still photography, but they didn’t offer it where I was. So I was this person who ended up shooting. I made a couple of my own films, and then I ended up shooting mountains of short films. And it all went from there.

Cinematography of “Maxxxine” by Eliot Rockett

Kirill: Looking back at when you started and now, did you go through all five stages of grief around the transition from film to digital?

Eliot: I was in graduate school at NYU and I finished in 1991, so it’s been a while. I started doing a lot of music videos in the ’90s. I moved to San Francisco, I kept doing music videos and also a bunch of computer company corporate work, and shooting one or two small independent features each year. And I resisted shooting anything on tape. I told myself that I was going to shoot stuff on film, and if the job wanted to shoot something on video, I was not going to do it and somebody else can do it.

Eventually at some point, the first Sony HD camera came out, and it was the time for me try it out and see what the deal is. So I started shooting a little bit of stuff in HD here and there, but I was very much not a big fan of it. As the years went by, I would keep doing a little bit of HD stuff and predominantly shooting a film. Much later when I moved to Portland, Oregon, I got hired on the NBC show “Grimm”, and they were shooting it on the original first Alexa. That was it, here we go. That’s what they’re doing. This is what we’re going to do. That show ended up going for six years, so for six years, I shot digitally.

By the time I was done with that show, digital had just eclipsed film. That was a six year transition where I was doing this one show, and everything else started moving very quickly. Alexa and Red were taking over everything. So by the time I got done with “Grimm”, everybody was shooting digitally. I didn’t go kicking and screaming into it. It was a segway into it.

Cinematography of “X” by Eliot Rockett

Continue reading »

![]() Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.![]()

![]()

![]()