I’m not going to take credit for the story, nor would I claim a perfect analogy. But here goes.

Imagine you’re in a room with ten screaming babies. As all of them are screaming at the top of their lungs, you start feeding them one by one. You’re done with one, and there are nine screaming babies left. Some time passes and you’re done with another one, and there are eight screaming babies left. Some time passes and you’re done with another one, and there are seven screaming babies left. And it doesn’t feel like you’re making any kind of progress because as long as there is at least one baby screaming, you can’t get any peace.

That’s how it can feel to be a programmer on any reasonably sized project. Where screaming babies are bugs in your incoming queue. They never stop demanding your attention, and they never stop screaming at you. Unless you make peace.

If there’s one axiom of software development that I hold inviolable, it’s that there will always be bugs. You can surround yourself with a bunch of processes, or do extensive code reviews and endless testing rounds. But the bugs will always be there. If anybody tells you that their code doesn’t have bugs, just shrug and walk away. They have no idea what they’re talking about.

Make peace with the simple fact that the code you’re shipping today has bugs.

Some bugs are scary. You need to tackle them. Some bugs, on the other hand, are these little tiny things that simply don’t matter. The problem with most (probably all but I haven’t tried them all) bug trackers is that the scary bugs in your queue look exactly the same as the tiny bugs. Most of the time the only difference is going to be in the single digit in the priority column. Or maybe the scary bugs will have light red background across the entire row. Or maybe the tiny bugs will use lighter text color. But they probably won’t.

And so you stare at your queue and you feel that you just can’t win. No matter how much effort you throw at that queue, as long as you’re not at zero bugs, they are screaming at you. And every time you fix a bug, you touch your code base. That’s another bug that you’ve just added. And every time you fix a bug, you get assigned a couple more.

Make peace that not all bugs are created equal.

Zero Bug Bounce is a fiction that some people invented to make peace for themselves and to create an illusion that they are in control. So at some point in the cycle everybody looks at the pages upon pages of bugs in your project queue, frowns and then mass-migrates a bunch of bugs to the next release. And to the next one. And to the next one. And at some point some bugs have been bumped out so many times that you might as well ask yourself some very simple questions. Do those bugs matter? Do they deserve to be in the queue at all?

Make peace that not all bugs are actually bugs.

Sometimes a feature that you’ve added to your product just doesn’t work out. It doesn’t get the traction you’ve expected. Or it’s not playing well with some other features that you’ve added afterwards. Or you’re not even sure how much traction it’s getting because you forgot to add logging, and there’s nobody on the team who actually cares about this feature after the guy who did it left the team and you’re in the middle of the big redesign of the entire app and why should you even be bothered spending extra time on that feature. Phew, that was a bit too specific.

And of course there will always be somebody who used that feature. And now that you’ve taken that toy away from them, they are screaming at the top of their lungs. And you cave in and bring that feature back. Well, in theory at least. But it’s been redesigned to fit into the new visual language of the platform. And now somebody else is screaming at you because you’ve changed things. All they want is just a teeny tiny switch in the settings that leaves things they way they used to be. Sure, they want new features, as long as they look exactly like the old features. But that’s a topic for another day.

Make peace that your work is never done. That if you want your work to be seen, you have to ship. Make peace that the work you ship will have bugs. Take pride in things that work. Develop a sense to know scary bugs from fluff. And develop a thick skin to ignore the screaming.

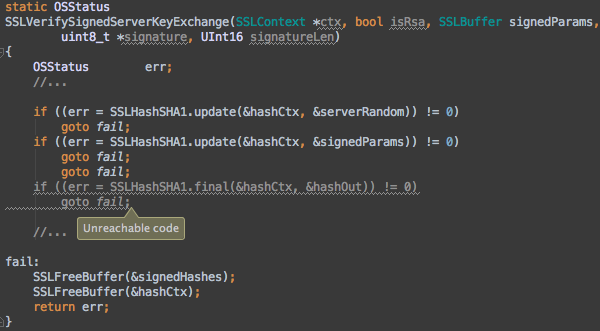

If only they used code guidelines that mandated braces around all blocks. If only they had unit test for this module. If only they had better static analysis tools. If only they had better code review policies.

There’s a lot of hand waving going around in the last couple of days, with everybody smugly asserting (or at least implying to assert) that they would never, in a million years, have made such a stupid mistake. And that’s what it is. Plain and simple. A stupid mistake. With very serious implications that reach into hundreds of millions of devices.

Except that stupid mistakes happen. To everybody. Unless you don’t write code. And if you write code and you really truly believe that you are not capable or making a mistake such as this… Boy, do I have a bridge to sell you.

Which brings me to my (almost) favorite thing in the world. Smugly asserting that I knew better than them and quoting myself:

My own personal take on this is that interacting with computers is too damn hard. Even given that I write software for a living. Computers are just too unforgiving. Too unforgiving when they are given “improperly” formatted input. And way too unforgiving when they are given properly formatted input which leads to an unintentionally destructive output. The way I’d like to see that change is to have it be more “human” on both sides. Understand both the imperfections of the way human beings form their thoughts and intent, and the potential consequences of that intent.

Do I have a solution for this issue? Are you f#$%^ng kidding me? Of course I don’t. But it kills me to realize that after all these decades we are still living in a stone age of human-computer interaction. An age when we have to be incredibly precise in how we’re supposed to tell the computers what to do, and yet to have such incredibly primitive tools that do not protect us from our own human frailty.

Random musings as NFL gets into the last week of the regular season and both Saints and Cardinals are at 10-5, with only one of them going to the playoffs. Since they’re not playing each other, we may see an 11-5 team not going to the playoffs this year. And only three years ago Seahawks won their division and went to playoffs at 7-9.

There’s some math laid out in here [PDF] that looks at the schedule balance of an NFL season, and while on average it appears that in most cases we do see the best teams from each conference going to the playoffs, I always wondered what is the worst case scenario.

There are two extremes here. The first one is how bad can you be and still get to the playoffs. The second one is how good can you be and still watch the post season on the TV.

The first one is simple. Each conference has four divisions, and every division is guaranteed a spot in the playoffs (aka Seahawks ’10). If you’re not familiar with how the regular season schedule is determined, here’s how it works. For the purposes of this first extreme, it’s enough to know that each team plays the three teams in its division twice (home / road), and then 10 games elsewhere in the league. What’s the absolute worst? Well, you can get into the playoffs with zero wins. That’s right, zero. How? Imagine a division with four really bad teams, and every game in that division ending at 0:0 (or any tie). And then every team in that division loses the rest of their 10 non-division games. In that case you’d eventually get to a very awkward coin-toss to determine which one of these four teams gets the “first place” in the division. Unlikely? Extremely. Possible? Of course.

Now to the other extreme. How many games can you win and still miss the playoffs? The answer is 14 (out of 16 games you’re playing) – if my math is correct of course. Let’s look at the scheduling rules more closely.

When the league expanded to 32 teams, it brought a very nice balance to the divisions themselves and to the schedule. Two conferences, four divisions each, four teams each. All hail the powers of 2! By the way, there’s additional symmetry that you get to play / host / visit each other team every 3/4/6/8 years (depending on the division association).

Back to who gets to the playoffs. Every division sends its first place, with two more spots (wildcards) left to the two best teams in the conference after division leaders are “removed” from the equation. This means you can be a really good team and still not get into those six. The conditions are quite simple really (as one of Saints / Cardinals will see this Sunday). The first one is that you have an even better team in your division that takes first place. The second one is that you have two better teams elsewhere in the conference (such as 49ers that already secured the first wildcard spot for NFC).

Let’s look at the numbers now. How can we get to the 14-2 record and still miss the playoffs?

In the following scenario we have NFC East as NE, NFC West as NW, NFC North as NN, NFC South as NS, and their counterparts in AFC as AE, AW, AS and AN. Let’s choose three random divisions in NFC, say NE, NN and NS.

A team in NE is playing 6 games in NE, 4 in NN, 4 in AW and 2 in NS/NW. A team in NN is playing 6 games in NN, 4 in NE, 4 in AN and 2 in NS/NW. A team in NS is playing 6 games in NS, 4 games in NW, 4 games in AE and 2 games in NN/NE.

In general you meet all teams in your division twice, all teams in another division in your conference once, all teams in a division in the other conference once, and then two teams from the other two divisions in your conference that finished at the same place as you last year.

What we’re trying to do is to get as many wins as possible for the #2 team in each one of our divisions (NE, NN and NS). There are only two wildcards available in each conference, and we don’t care what happens in NW or the entire AFC.

For each pair of teams in NE, NN and NS we want to maximize the number of wins while still keeping in mind that they play each other. This year each team from NE plays each team in NN twice. And each team in NS plays one team in NN and one team in NE – based on its position in the division last year.

Let’s look at NS first. Team #1 and #2 get four wins each playing #3 and #4 in their division. Then they split the wins in their two games, getting at 5-1 record for each. They then win all 4 games against NW, getting at 9-1, and all 4 games against AE, getting at 13-1. Finally, assuming that our two teams finished last year at positions that get them scheduled against NE / NN teams that will not be finishing at #1 / #2 teams this year, both teams get at 15-1 – all without taking a single win away from the four teams in NE / NN that we’ll be looking at shortly.

Now to NE / NN. We’ll look at NE, while the same logic applies to NN. Once again, teams #1 / #2 win all four games against #3 / #4 and split their own two matches, getting at 5-1 both. Now they play four games against NN. They win both games against #3 / #4 teams, getting at 7-1 each, and split the wins against #1 / #2. We need to split the wins in order not to take away “too many” wins from those two teams in NN. So we end up with 8-2. Now they win all four games against AW, getting at 12-2. Then they get one win against NW getting to 13-2. Finally, they have one game to play against NS. Applying the same selection logic, the best scenario for us is to get them scheduled against a team that is not at #1 / #2 this year (but at the same position they were last year), which gets both teams to 14-2.

And now the same goes to the first two teams in NN, getting them to 14-2 both. Which is why we need to split the NE/NN games between #1/#2 teams.

Now we have #2 team in NS at 15-1 and #2 teams in both NE and NN at 14-2 each. One of them will have to stay out of playoffs. Unlikely? Extremely. Possible? Of course.

Waving hands in the air, it feels that the first scenario is much less likely to happen due to how few ties we usually see in the league. Even though it can happen in any one of the eight divisions, and the second scenario involves three divisions in the same conference, it’s still much less likely to happen. What if we remove the ties from the equation?

A 4-team division has every team playing every other team twice. All in all you have 12 inner-division games in every division. If no game ends in a tie, the most extreme case is that all teams end up winning and losing 3 games in their division, and losing all other 10 games, with 3-13 record for each. One of them will go to the playoffs. That would also answer the question of how many games can you lose and still go to the playoffs. In the previous scenario (no wins), you have every team in the division at 0-10-6 record, so it’s “only” 10 losses. With this scenario you have a 13-loss team going to the playoffs.

It would appear that this new extreme is more likely to happen, as it only involves teams in a single division, and the other one (14-2 not going to playoffs) involves teams in three divisions.

Now two questions remain. Can we get to a 15-1 record and stay out of playoffs? And, more importantly, is there a fatal flaw in the logic outlined above?

One of my recent resolutions (not for 2014, but for mobile software in general in the last few months) was to evaluate designs of new apps and redesigns of existing apps from the position of trust. Trust in the designers and developers of those apps that they have good reasons to do what they do, even if it’s only one or two steps on the longer road towards their intended interaction model. But Twitter’s recent redesign of their main stream keeps on baffling me.Putting apart the (somewhat business-driven from what I gather) decision of “hiding” the mentions and DMs behind the action bar icons and adding the rather useless discover / activity tabs, I’m looking at the interaction model in the main (home) stream.

Twitter never got to the point of syncing the stream position across multiple devices signed into the same account. There is at least one third-party solution to do that, which requires third-party apps to use their SDK and users to use those apps. The developer of that third-party solution has repeatedly stated that in his opinion Twitter is not interested in discouraging casual users that check their streams every so often. If you start following random (mostly PR-maintained) celebrity streams, it’s easy to get lost in the Twitter sea, and when you check in every once in a while and see hundreds – if not thousands – of unread tweets, you might start feeling that you’re not keeping up.

As I’ve reached the aforementioned decision a few months ago, I’ve uninstalled all third-party Twitter apps I had on my phone, and switched to the official app. It does a rather decent job of remembering the stream position, as long as – from what I could see – I check the stream at least once every 24 hours. When I skip a day, the stream jumps to the top. It also seems to do that if the app refreshes the stream after I rotate the device, so some of this skipping can be attributed to bugs. But in general if I’m checking in twice a day and am careful not to rotate the device, the app remembers the last position as it loads the tweets above it.

In the last release Twitter repositioned the chrome around the main stream, adding discover / activity tabs above it and the “what’s happening” box below. While they encourage you to explore things beyond your main stream, it also looks like they’re aware that these two elements take valuable vertical space during the scrolling. And the current solution is to hide these two bars when you scroll down the stream.

And here’s what baffles me the most. On one hand, the app remembers the stream position, which means that I need to move the content down to get to the newer tweets (as an aside, with “natural” scrolling I’m not even sure if this is scrolling up or scrolling down”). On the other hand, the app hides the top tabs / bottom row when I move the content up.

Is the main interaction mode with this stream is getting to the last unread tweet and then going up the stream to skim the unread tweets, as hinted by remembering the stream position? Or is it getting bumped to the top of the stream and scrolling a few tweets down just to sample the latest few entries in it, as hinted by hiding the two chrome rows and providing more space during the scrolling?

I don’t want to say what the app should or shouldn’t do in the stream (as pointed out by M.Saleh Esmaeili). It’s just that I can’t get what the designers intend the experience to be.

A few days ago The Verge has posted an article around metric-driven design in Twitter mobile apps, an for me personally the saddest part of this article is how much they focus on engagement metrics and how little the guy talks about informed design. Trying to squeeze every possible iota of “interaction” out of every single element on the screen – on its own – without talking about the bigger picture of what Twitter wants to be as a designed system. Experiments are fine, of course. But jacking up random numbers on your “engagement” spreadsheets and having those dictate your roadmap (if one can even exist in such a world) is kind of sad.

When every interaction is judged by how much it maximizes whatever particular internal metric your team is tracking, you may find yourself dead-set on locating the local maximum of an increasingly fractured experience, with no coherent high-level design, and no clear path that you’re taking to arrive to the next level. Or, as Billie Kent’s character in Boardwalk Empire says, “always on the move, going nowhere fast.”

![]()