My most-used browser extension is, undoubtedly, Clearly by Evernote (available for both Chrome and Firefox). It takes something that looks like this:

and turns it into this:

Gone is all the crap that the site wants you to see, and left is the actual content that you have arrived to read. Clearly has a few presents for font choices, sizes and color schemes, and it also allows one to create a completely custom scheme. After staying with the default Clearly theme for a few months I have become quite aware of how comfortable my web reading has become. With a single click of a button I am left with only the article itself. But it went well beyond it, and it took me some time to understand the reason.

As I started the gradual redesign of my own blog a few months ago, I kept coming back to one single question. Imagining myself as the reader of my blog, what would it take me to not click the Clearly button? And so, little by little, I started to take away the visual cruft. Gone is the harsh glare of pure white background and high contrast of pure black text. Instead, I use a quasi-random light-gray texture tile that provides relief while still emphasizing the horizontal direction of the text. Gone is most of the heavy “About me” blurb in the right side bar, and around half of the other sidebar content. Instead, a smaller blurb ends with the “more” link, and the entire sidebar content uses a smaller font size and lighter shade of black. Finally, gone is the entire comment section, as its visual weight has stopped carrying enough value to justify its continued presence. But there was still one more piece left.

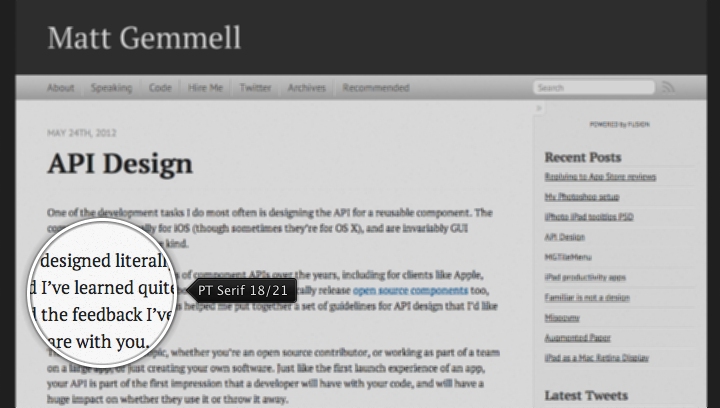

Much can be (and has been) said about the choice between serif and sans fonts. There are studies that compare reading speed and legibility, and there are polarized opinions behind every choice. Some sites even go as far as providing a switcher between different fonts, absolving themselves of the hard option of making an actual decision. I wanted to make a decision, and that decision was guided by the same question – why do I enjoy using Clearly so much, and what would it take me to not click that button on my own blog? Which has finally brought me to realize what made my reading so enjoying and comfortable – the default choice of a large variant of PT Serif font.

From there I’ve spent some time going over some of my favorite sites and blogs, looking at their typography and gathering more data to make the choice for my own blog. There was one thing that I was quite clear about – I wanted to have an enjoyable lean-back reading experience, and that ruled out small font sizes from the very beginning. And the more I looked at sans fonts at larger sizes (18 points and above), the more I saw that I was going to use a serif font. Which left two questions – which font and which font size.

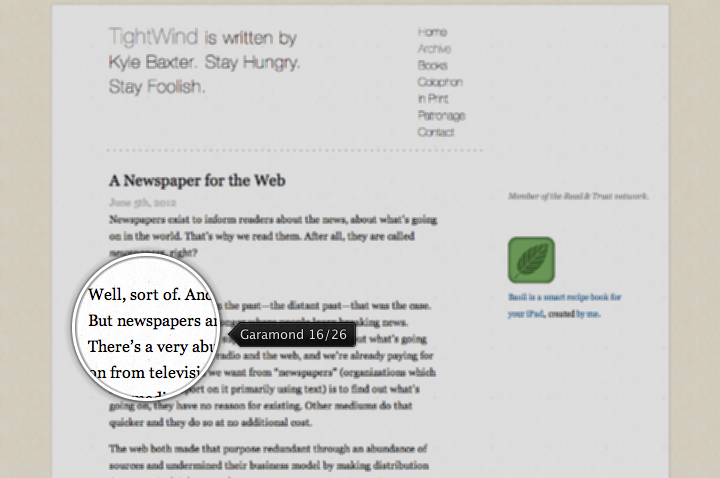

Here are few of the sites that I looked at in my quest (linking to individual entries and detailing the font size / line height). First, Kyle Baxter‘s tightwind.net that uses Adobe Garamond:

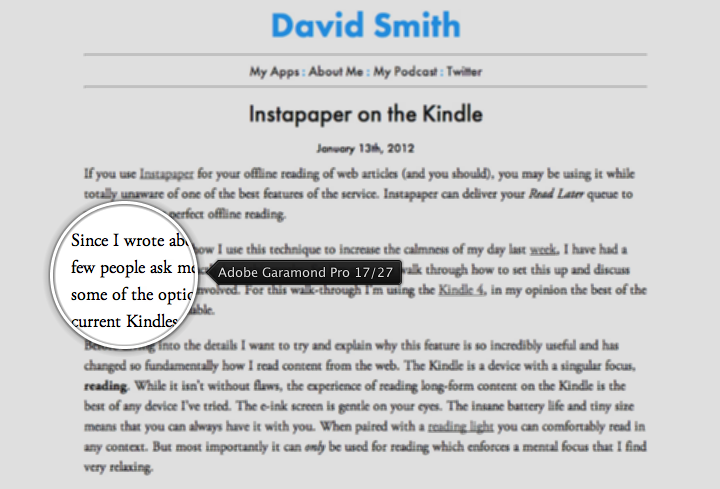

Next, David Smith‘s david-smith.org that uses Adobe Garamond Pro:

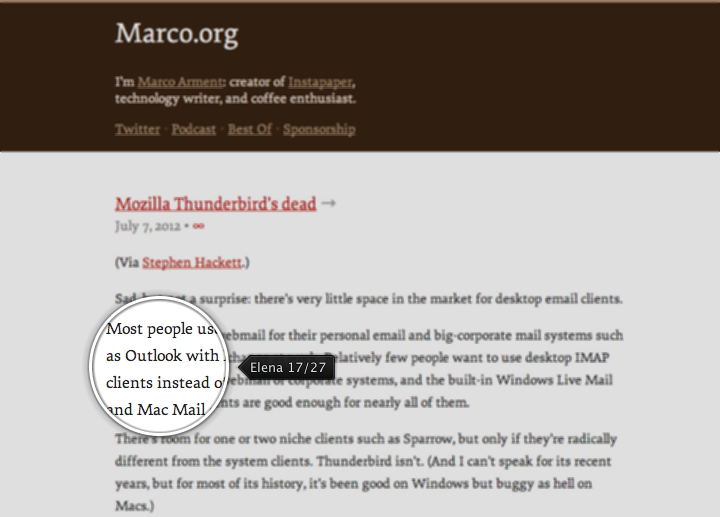

Next up Marco Arment‘s marco.org that uses Elena:

Next, Matt Gemmell‘s mattgemmell.com that uses the aforementioned PT Serif:

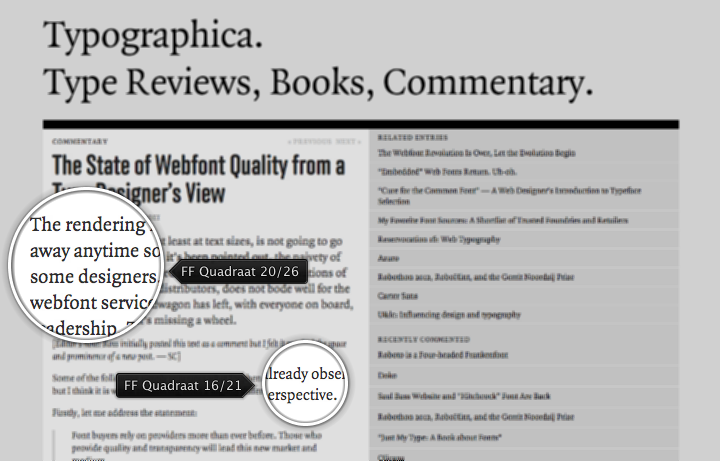

Next one is typographica.org that uses FF Quadraat in two sizes – a bigger one for the opening paragraph, and a smaller one for the rest:

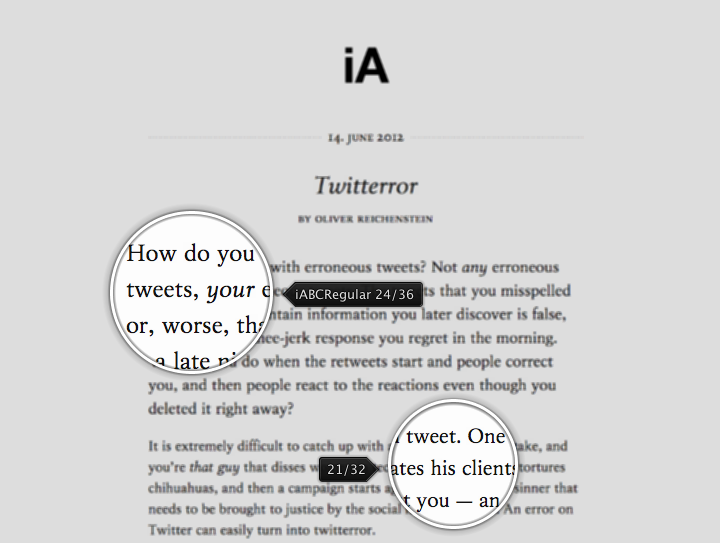

And finally, Oliver Reichenstein‘s informationarchitects.net that uses his own custom iABC font in two sizes – a bigger one for the opening paragraph, and a smaller one for the rest:

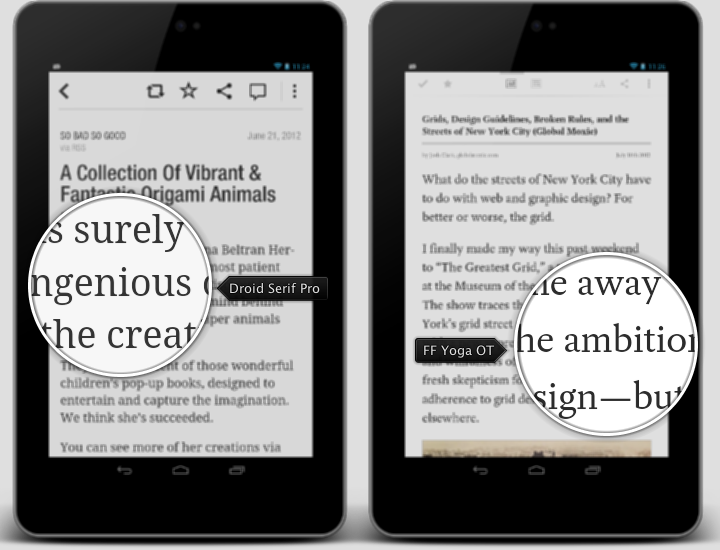

As a small detour, I’ve also looked at two of the applications I use occasionally on my mobile devices for more comfortable reading – Flipboard and Pocket:

Pocket allows choosing between two bundled fonts – the sans Proxima Nova and the serif FF Yoga OT. Flipboard bundles the sans Neue Helvetica for the main browsing tiles, and uses web views to render the actual articles. The article rendering is not very consistent, using Droid Serif Pro for most of the articles, and a variety of sans and serif fonts for others. This is combined with the lack of user choice to enforce usage of a single consistent font, taking away one of the “selling” points of such an app – consistent, uncluttered and enjoyable reading experience.

The six examples of different web sites shown above are ordered based on the font size – from smallest (16 points) to largest (24 points). The “large” setting of Evernote’s Clearly is 20 points with line height of 30 points, and this was the minimal font size that I was comfortable with. Finally, I did not want to explicitly highlight the first paragraph as done in the last two examples. I do understand the perceived importance of the opening paragraph for those that do quick skimming, but that is not my actual target case.

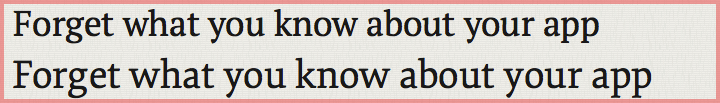

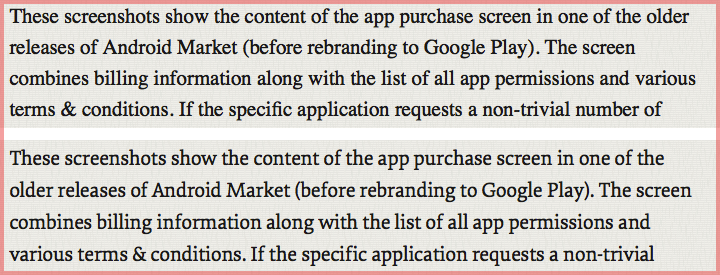

PT Serif is a free and decent looking serif font. This is what I’ve been using on this blog over the last couple of months. However, it has certain problems with kerning. Here is a very small comparison to Elena, my eventual font choice:

The top line (PT Serif) is quite irregular in the very first word. It starts with quite spacious gaps between the first three letters, and then “rushes in” to complete the next three ones. Compare it to the bottom line (Elena) that has a better consistency, even though some of the gaps still feel a tad too wide.

And this screenshot compares how PT Serif (top) and Elena (bottom) handle the body text under my eventual selection of 21 points for font size and 32 points for line height. You can see the better kerning in the words “before” (2nd line), “billing” (3rd line) and “trivial” (4th line), just to point out a few.

Elena is a great and very affordable web font. If you happen to read this article outside of its original form, you’re more than welcome to click through to the original format to judge for yourself. It is rather unfortunate that I only use it on the Mac machines. Much has been said about the difference between rendering engines on Windows and Mac. I would only say that I have not seen a single serif web font that looks good on a Windows browser – including all the sites mentioned here. For now I’m staying with Georgia as the default font for non-Mac platforms.

This would not be complete without adding a few links to sites that provide my daily dose of typography inspiration. In no particular, although alphabetical order, they are:

The world of multi-hundred cable channel bundles is deceptively simple if you’re a customer. Pay $XX/month and get a unified access to a very large number of channels.

Some channels are more “successful” in that their shows attract more awards, online buzz, cross-sell merchandise, higher salaries for their cast & crew when they are invited to other productions etc. Some shows have a much higher investment from the production studios.

The channels are sold to the cable networks in bundles – such as, for example, a 24-channel bundle from Viacom. Some bundles have a few very strong channels and a lot of fillers. Some bundles have a more even distribution of their quality.

At the end, it’s a leverage battle between cable networks that aggregate the disparate bundles into their own mega-bundles and the production companies behind each bundle.

Those $XX/month get distributed between the different bundle providers based on whatever terms the sides agreed on. Companies that provide stronger bundles will feel that they have more leverage to negotiate a bigger slice of that $XX/month for them. On the other hand, they wouldn’t want to see their current slice becoming smaller when their bundle is having an off season.

So when one bundle provider uses its leverage to negotiate a bigger slice of the pie, the cable network can agree fully, negotiate or refuse. And here you suddenly have many more players involved, each with its own leverage.

If you (as the cable network) agree to give a bigger slice of the pie, there’s less of the pie left to everybody else including yourself. It either eats into your own margins, or gets deducted from somebody else’s slice – which they won’t be happy with. Or you can increase the pie by increasing the monthly subscription fee – which your customers won’t be happy with. And even if the cable network takes that money out of its own margin, there’s blood in the water. All the other bundle providers see that there’s an extra money to be made, if only they apply their leverage. And you can’t keep these things secret.

So what we are seeing now is just a game of leverage. Viacom feels that their bundle is such a strong offering that they can demand a bigger slice of the pie, or the same size of a bigger pie. DirecTV is using their own leverage of access to the actual paying consumers. Each side is using an arsenal of tricks to portray itself as the “good guys” and inviting the public to apply pressure on the other, “inflexible” side that is withholding the content from the paying consumer.

It’s the 2010 battle of Time Warner vs. Fox all over again. At that time Fox had wanted a $1/customer/month more from each of the $15M Time Warner subscribers. As the time for Sugar Bowl got closer, the sides agreed to the rumored 50-cent increase in Fox’s slice. It’s the more recent disagreement between Dish and AMC, where even the season premiere of “Breaking Bad” was not enough leverage for AMC to get access to Dish’s $14M customer base.

Select file

Invoke the copy operation

Select destination folder

Invoke the paste operation

The sequence of steps to copy a file to a different folder is now so ingrained in my motor memory that I don’t question why the steps have to be in this specific order. You select something, and then you “say” what you want to do with it. It only “feels” natural because we’ve been doing it for so long.

In English you would say “Copy A to B” when you’re asked to describe what you’re doing. But when you actually do it, it’s “A copy B to”. Sort of a reverse Polish notation in a sense. But following the rules on English grammar only makes sense if you insist that the sequence of actual steps must conform to those rules no matter what is the local dialect. In English, the only way to say this is “Copy A to B”. But in Russian, you can use any one of the following:

- Copy A to B

- A copy to B

- To B copy A

- Copy to B A

- A to B copy

- To B A copy

Here the only thing that stays the same is “to B”. We end up with 3 parts of the sequence and 3! ways to combine them. To a native speaker the end result is the same, but the importance is conveyed by the order. The part that comes first is the more important, and the part that comes last is the least important. There is a strong implicit importance relayed by the ordering.

But I wouldn’t really expect a localized version of Windows, OS X or Linux to allow me to do all six possible sequences to copy a file to a different folder. Ignoring the vast complexity of supporting something like this for all possible languages and dialects, it’s quite counter-productive to expose radically different ways to achieve the specific result depending on the specific natural language of the user. Or is it?

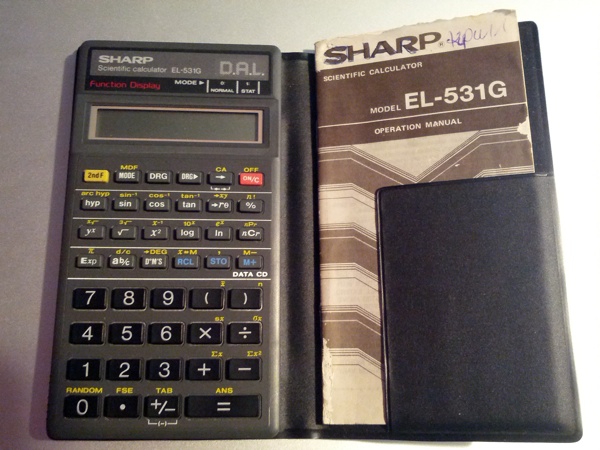

I had a little obsession with calculators growing up. I actually had only two, but I’ve spent an inordinate amount of time doing various tricks with them. The first one was of the usual variety. Every math operator was an implicit “equals”. If you did 2+3×4, you got 20. If you wanted to do a sine of 30, you did 30 sin. It’s only weird to have these differences if you stop thinking about it. It’s perfectly logical to have these differences if you grasp at least the basic complexities of implementing a simple calculator in your starter programming language of choice.

And then there was Sharp EL-531G with its D.A.L. – Direct Algebraic Logic. The way to compute something was to start typing the same exact sequence as you have in your problem. Sine of 30 is sin 30. 2+3×4 is evaluated only when you press = and then you get 14. The small downside is that if you’re typing quickly and don’t check every single operand, you won’t discover “obviously” wrong intermediate results. The much bigger upside is that you don’t start mentally regrouping parts in a complex formula just to fit the implementation model. The computation follows the rules of precedence, and you also have the brackets to control it if necessary.

The notion of fluent interfaces became quite popular a few years ago. In the “regular” object-oriented approach, copying a file would look something like this:

FileRef reference = new File(“path/to/A”).copy();

new File(“path/to/B”).paste(reference);

With a fluent interface, it would become something like this:

FileUtils.copy(“path/to/A”).to(“path/to/B”);

Where FileUtils.copy would return an object that has a to method that does the actual copying of the bits. Fluent interfaces are often tweaked and judged on the merits of how close they get to the rules of English grammar, with various techniques to encapsulate the complexities of chain links that arise because of that.

But what if I’m not an English speaker? A fluent interface based on the rules of English grammar is no more understandable or fluent, if you will, if it doesn’t follow the rules of my native grammar. You’re just trading one convention over another. Long chains of fluent calls are also counterproductive to handle failures. If you have more than one link, how do you handle and debug failures? Should a failure at a middle link roll back the results of the previous links? This also brings another interesting point which goes back to N! variations allowed by the rules of Russian grammar. If a native Russian programmer exposes a fluent API that allows all possible variations, does it mean that the implicit importance of the order affects how you handle intermediate failures?

It would be weird if I had to first press Cmd+C and only then to select a file to start the copy process. It would be equally weird to press Cmd+V and only then to select the target folder. How would you even “tell” to the computer that you are at the target folder and not in the middle of navigating to it by clicking around? But it’s only weird because of the 20-year strong rule of WIMP interaction model.

If you move away from files organized in folders towards files tagged by labels, things become different. If you move away from action “verbs” denoted by commands on the selected object toward a more fluent voice-controlled interaction, things become different. If you move away from the very notion of files as boundary units delineating your data, things become different. How different? I don’t know. But the next 20 years will be quite interesting.

Another year is gone, and it’s time to review what has happened on this blog over the last twelve months.

2011 has been a busy year for the Android Market client that has undergone a complete redesign to bring it into the world of browsing, searching and purchasing digital media. The “Designing for the mobile form factor” presentation at AnDevCon conference in March was followed by a series of detailed entries about the design and implementation aspects of the new client. I took a deeper look at synchronized scrolling, swipey tabs and carousel animations, also talking about the reasons not to provide full source code for those areas. I also highlighted the importance of pixel-level details, and proper collaboration between developers and designers.

As we worked on bringing a unified experience to a variety of form factors, we started to define and refine principles of responsive mobile design. After making the presentation at AnDevCon II conference in November, I followed up with the four-part series that answered three underlying questions: what are we designing, why are we designing it in a certain way and how are we implementing the target design (part 1, part 2, part 3, part 4). As we continue refining and polishing the application across the entire gamut of supported devices, this blog will be updated with more details on both the planning and implementation aspects of responsive mobile design. And on a related note, I’ve finally collected my thoughts about vector icons and put them in words.

A look at the colors of Tron: Legacy was just a beginning of a much bigger part of Pushing Pixels. A deeper look at the art of Tangled and the transition to 3D shooting and projecting has started a new chapter. Over the last nine months I’ve interviewed a number of creative artists working on various aspects of motion productions that I’ve found particularly impressive in the recent years. I’ve talked to Martin Ruhe about the cinematography of “The American”, Drew Boughton about the art direction of “Unstoppable”, Phillip Baker about the production design of “Chloe”, Claire Keane about the art of “Tangled”, Bradley GMUNK Munkowitz about the visual effects of “Tron: Legacy”, Luke Dunkley about the editing of “The Crimson Petal and the White”, Rosalina Da Silva about the make-up of “Tron: Legacy”, Mark Scruton about the art direction of “Easy Virtue”, Sarah Horton about the art direction of “The International”, John Greaves about the storyboarding of “Edge of Love”, Jonathan Freeman ASC about the cinematography of “Edge of Love” and Anne Seibel about the production design of “Midnight in Paris”. I’ve also talked with Kyle Westphal about the craft of film projection, and with music director David McClister. You should definitely expect more interviews in 2012.

I also looked at the costume design of “The Tourist“, the rainbow colors of “Burlesque“, the colors of “How Do You Know“, the colors of “Emma“, the set design of “Mr and Mrs Smith“, the art of “Cracks“, the colors of “No Strings Attached” and the colors of “Twilight“. Finally, a smaller series looked at the iconic images of “North By Northwest“, “To Catch a Thief” and “Key Largo“.

The Retro:Active series started in October 2010 saw the total of 368 posts in 2011. This series showcases the fusion of modern and vintage in visual and industrial design, fashion, photography, typography, illustration, animation and other related areas. This is one of my main sources of inspiration, and expect it to continue well into 2012.

Pushing Pixels is here to stay, and it will only get better. If you still have not subscribed, click on the icon below to stay tuned in 2012!

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()