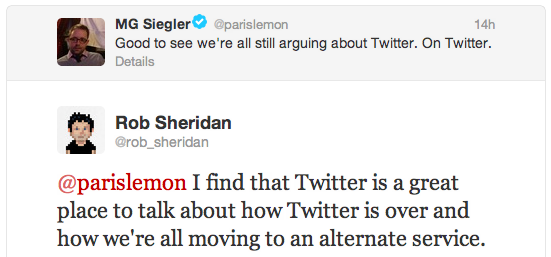

Ben Brooks on his decision to leave Twitter:

I’ve stopped posting new updates. I’m only checking it a couple times a day. And if Twitter doesn’t do an about face I’ll be done with it very quickly. I’m giving them one last chance, but also slowing my usage to a crawl — imagine the power of the entire nerd community doing this. The easiest way to making Twitter take notice, is to remove your eyeballs from their advertising, and devalue the network by reducing the size of it.

First, nerds are running third-party clients that do not show promoted tweets or ads. Second, the number of people retweeting every single Justin Bieber’s tweet is vastly more than the number of people discussing the latest API restrictions. Third, removing these eyeballs is actually improving Twitter’s bottom line, as it is reducing the strain on backends and does not hurt the current business model any single bit.

The flexibility of a human mind continues to amaze me. Somehow my kids got hooked on “Bubble guppies”, and my four-year old son identifies himself with the teacher, Mr Grouper. And yet he only smiled when I told him that I had grouper fingers for lunch on Monday. For him it’s just another external signal to observe, absorb and reconcile, even as the brightest of the humankind struggle in their feeble attempts to put intelligence in artificial intelligence.

The flexibility of a human mind continues to amaze me. Somehow my kids got hooked on “Bubble guppies”, and my four-year old son identifies himself with the teacher, Mr Grouper. And yet he only smiled when I told him that I had grouper fingers for lunch on Monday. For him it’s just another external signal to observe, absorb and reconcile, even as the brightest of the humankind struggle in their feeble attempts to put intelligence in artificial intelligence.

A work of fiction may poke fun at a grown man displaced centuries ahead of his time and his failure to adjust to the technological and societal norms, but in reality a human mind will adapt. A human body can only withstand a miniscule variation in the characteristics of the physical environment. The ability of a human mind to adapt, on the other hand, is on a completely different scale. Placed in a new environment with a new set of constraints, the human mind will skip the why am I here, and instead will probe the boundaries and say I’m here, how do I adapt and what can I do?

File systems are a given in any modern computing environment. From magnetic tapes to optical disks, from audio cassettes to flash drives, from punch cards to cloud storage, it’s hard to imagine doing anything useful without being able to partition the data into individual chunks, without being able to store, retrieve and modify them at will. Any non-trivial collection of chunks needs to be organized, in the physical world as well as in the digital one. In one form or another, folders are physical entities that create separation and grouping in the physical world. It wouldn’t take a large leap of faith to translate this concept into the digital world. A world which is not bound by the same limitations. A world in which you can put as many files as you need in a single folder. A world in which nested folders are just a natural continuation of existing ways to partition and group the data. A world in which you can create a symbolic link to a file or a folder and reference the same data from multiple places, as if you had identical copies of it. A world that continues expanding its boundaries and frees the human mind from the constraints of the physical world.

Which is why I only partially agree with Oliver Reichenstein‘s take in his “Mountain Lion’s New File System“:

The folder system paradigm is a geeky concept. Geeks built it because geeks need it. Geeks organize files all day long. Geeks don’t know and don’t really care how much their systems suck for other people. Geeks do not realize that for most people organizing documents within an operating system next to System files and applications feels like a complicated and maybe even dangerous business.

The concept itself was certainly not invented by geeks. The need to manage large volumes of heterogeneous data did not arise with the advent of computers. The pace of creating the data in pre-computer world was certainly limited by the means of production and dissemination, but digital folder systems are not much different from their physical counterparts. But extending that physical notion into the digital world had interesting consequences.

I’m here, how do I adapt and what can I do? Adapting is easy. If I know how to group related documents into one binder on my desk, and how to put labels on different binders, and how to stack binders on different shelves, and how to label different shelves, I’m all set to start organizing the matching files and folders on my computer. The evolution of file management tools has provided an increasingly expanding array of tools to copy, move, rename, split, collate and combine files across different folders. File as the basic unit of storing information has defined the way we’ve interacted with computers over the last fifty years.

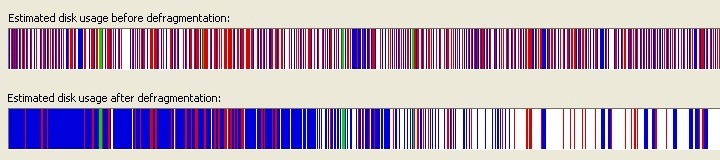

I vividly remember running a variety of disk defragmentation tools in the late 1990s. They were a necessity. Hard drives were reasonably large for documents, but on average they were not large enough to accommodate the increasing appetite for installing games and storing video files. The physical aspects of seeking sectors on rotating magnetic disks propagated all the way up to the runtime performance of the entire system, and required running defragmentation tools on the regular basis. You wanted the files to be clustered as tightly as possible to reduce the maximum seek time, and you never wanted a file to be split across different disc sectors.

There was a visceral, almost palpable pleasure to see the lines and squares (depending on the interface) to change colors and places. You could almost feel your files to snap together, you could almost feel that big video file to become one contiguous chunk, you could almost feel your computer to run faster.

This is why Vista’s defragmenter UI was such a disappointment. There is almost nothing to see, almost nothing to feel. There are passes, there is progress, but a little in the way to expose the work that is being done, the chunks of data that are being moved, torn apart and sewn back together. It’s almost as if the files are not there at all.

And what if there are no files? What would happen if that is your new boundary? What if instead of asking why, you say how do I adapt and what can I do?

What if there was no file explorer on your desktop machine, much like there is no file explorer preinstalled on your phone or tablet? What if you severed the mental connection between the visual representation of the data on your screen and the way it is encoded, transmitted and stored on a physical medium? Would you care if the pictures you have taken on the last trip to Europe were stored as one gigantic blob somewhere on your disk or in the cloud, if you were still able to view, edit and share them individually as you do today? Would you care if the document you are working on is saved as a single file, or as a binary blob in some relational database sharded and replicated across multiple cloud servers, merely represented as a single unit when you open it? And what is a single local file if not a binary blob delineated by the file system journal, and defined by its encoding?

How would you write an application using a system API that has no references to file objects, that has no specific definition of how and where each individual chunk of data is written? How would you design a system API that does not have such references? Would that make the life of system developers harder? What that make the life of application developers harder? And, more importantly, would that make the life of users easier? As long as all the sides accept the new paradigm, that is.

Indie devs keep on bitching about how they’ve helped bring Twitter to the masses and invent some of the features later adopted for official use. Stop bitching. It was a two way street. You amassed reputation, carved out a name for yourself, collected tens of thousands of followers on twitter, your blogs and your podcasts. Some clients were so popular that offers were made and acquisition deals were signed.

It was a community for a few, and then the VC money came in and they want to see a whole different kind of profit. Is it a different community than it was a few years ago? Of course it is. You grew in your popularity and influence, and Twitter did the same. It’s no more yours today than it was yours back then.

Seth Godin talks about tribes. There are two types of tribes that are relevant here. For each such indie dev, there’s his consumer tribe that is interested in following his stream. And then there is also the creator tribe encompassing like-minded devs, sparkling dialogs and conversations with threads that involve some people from their consumer tribes as well. In a sense, there is also a more amorphic meta-consumer tribe associated with that creator tribe, where people interested in following one creator are more likely to follow similarly oriented creators.

The creator tribe that I follow on Twitter is all ready to move to app.net, and yet there are only two people seriously talking about leaving Twitter. Because that creator tribe is ready to move, but not ready to lose its meta-consumer tribe. And so it stays, and keeps on bitching about staying.

One thing leads to another. It might not happen right away, but things part, drift and fall back in quite unpredictable ways. I’ve spent the first four years after high school studying geodesy, and finding out that I really wanted to be a programmer. Another four years and a degree in computer science later, the two crossed together in my first job.

My resume was, well, padded. During my last year of CS studies I took what was called a Software Lab, or rather two of them. In both I’ve worked with PhD students, writing software to put their theories to test. Both were about formal verification, and both involved computing and plotting proof graphs. I was also doing a part-time job on an internal research project that explored automatic translation between various academic and commercial verification toolkits. The general advice is to put the last two or three jobs on your resume and skip the rest, and I didn’t have much to skip. But it didn’t really matter.

As I sat down for my first interview, the guy across from me took one look at the first page of my resume and said “So you studied geodesy.” And that was pretty much it. I guess there were not a lot of computer science graduates coming across his desk that also could maintain an informed conversation about the UTM coordinate system and the difference between ED50 and WGS72 geoid models. The girl I was supposed to replace would not be leaving for another three months, but it didn’t really matter. They found me a space in between desks, and she was almost on her way out in any case.

Those were the days of AIX and Windows NT. I didn’t do much in the way of “traditional” user interfaces. Sure, I’ve thrown together a few simple wizard dialogs, a couple of buttons, a couple of checkboxes, a combobox here and there. But most of the time I was working with map data, reading it from various sources and drawing colored polygons on a map canvas. After my first project was done in early 2002, I’ve transferred to a different project that was just starting up. A project that would change the way I’ve looked at the pixels every since.

It was a throw-it-all-away and rewrite-everything-from-scratch kind of project. There were endless meetings about what technologies to choose and how to combine them together. XML was on the rise. Java was on the rise. Servlets were on the rise. UML was on the rise. And you know, you put a few senior architects together in the same room for a few months, and things are bound to get complicated. As I joined the project, the decision was done to do a hybrid client, Java below the surface and Delphi above the surface. Java code would do the heavy lifting of data transfer, persistence, querying and caching. But the UI requirements called for presenting complex ways to interact with data, and Swing was lacking in the department of commercial UI component libraries. On the other hand, Delphi had a surprising (at least for me) variety of very powerful component libraries from a wide variery of commercial vendors. Some of them even came with auto-generated binder layers that would allow Delphi components to do two-way data communication with Java code.

I was living in the Delphi world, still mostly working on the pixel level of map canvas. The guy next to me was doing the UI chrome around the canvas. One day I glanced at his screen and saw a bunch of calls to draw lines, rectangles and arcs. And the answer to my lazy “what’s that code mess doing?” was “drawing toolbars.”

That was late 2002. Microsoft Office was as popular as it would ever be, and the way it addressed the ever increasing feature growth and how it was exposed to the user was, for better or worse, the leading industry example. Office 97 has converged menus and toolbars into a single unified concept, and Office 2000 took the feature bloat to fight by introducing adaptive menus, adaptive toolbars and rafted toolbars (where one single toolbar row would fit two or more toolbars, and buttons would go in and out of the overflow menu based on frequency of use). Office 2003 has introduced task panes, and Windows XP that came out a year earlier was an enormous success for Microsoft. These two also marked a step away from flat, rectangular, steel gray control surfaces, adding softer corners, gradients and drop shadows. The success of both Office and Windows was undeniable, and vendors of UI component libraries were expected to match the sophistication of the Office user interface in both feature set and appearance.

I’ve never thought about the underlying implementation of core UI components. They were there to use, and that was it. Sure, Motif or Windows NT buttons look ugly now, but back then? I didn’t care much about the aesthetic appearance of the interface. That might also explain my lack of interest in how those components were actually drawn on the screen. Not that there was anything fancy to draw – just flat rectangles and a couple of darker outlines. Windows XP changed that. Office 2003 changed that. But if you were to ask me about how those are drawn, I would shrug and say “Who cares? It’s just a service provided to you by the operating system.”

While the operating system provided a certain set of UI components, those were not enough to create a fully-featured UI seen in Office 2000 or Office 2003. And our architects were pretty adamant to see all those and more. Adaptive toolbars that can be stacked vertically, horizontally and on all sides of the screen? Yes. Collapsible task panes stacked in an accordion, interleaving toolbars and mini-map canvas? Yes. Pivot grids with multiple nested child grids, frozen columns and auto-filtering? Yes. And many more. And the best thing? There was so much competition between Delphi component vendors that you could have all that and more for quite reasonable prices. And most came with an option to purchase the source license as well. And this is how I saw the underlying implementation of those components.

When I looked at the full implementation of the specific component library that we ended up purchasing, it was a shocking eye-opener. I had to go back and ask the guy if what I was seeing was indeed true. That they had to listen to every single type of mouse event for proper handling of mouse actions. That they had to listen to every single combination of keyboard strokes and modifiers to perform matching operations. That they had to compute the bounds of every single element within the specific toolbar, within each toolbar row and within each window chrome edge.

That they had to draw every single pixel of the component representation on the screen. Every single pixel of a toolbar outline, drop shadow, separator and overflow indicator. To precisely match the color of every single pixel. To precisely emulate the amount and texture of drop shadow so that it would match the appearance of XP and Office counterparts. To track every single mouse event to emulate the rollover, press and select events, drawing the inner orange highlights to match the appearance of XP. One pixel, one arc, one line, one rectangle at a time.

Pixels are magic. When you can control the color of every single pixel on the screen, you can do anything. But it’s also a lot of mundane, dirty and, at times, grunt work. I did my own TrueType rendering engine once, abandoning it when I saw how much work is involved in implementing the hinting tables. I did my own compositing engine with support for anti-aliasing and various Porter-Duff rules. I did my own component set and my own look-and-feel library. I did all of these because ten years ago I saw the pure power of pixels. And if you ever wondered why my blog is called “Pushing Pixels”, now you know why.