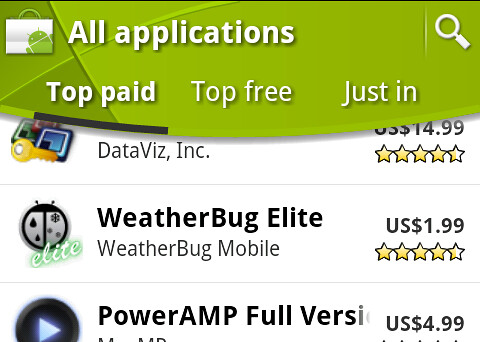

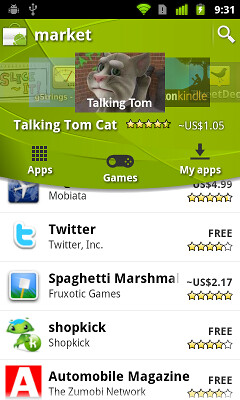

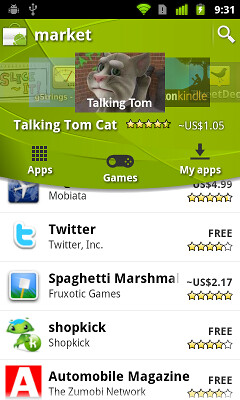

The recently redesigned Market client introduced an interactive carousel that features promoted apps and games relevant to the current page. The carousel lives in the main navigation area and allows the user to quickly browse the promoted content and view concise information on the specific app. In portrait mode, the carousel takes roughly 40-45% of the screen height (depending on the screen resolution), while in landscape mode it takes the left half of the screen. The landscape mode is, in my opinion, a major step forward in improving usability and content placement, but we’ve introduced a usability regression for the home screen in portrait mode, especially for smaller QVGA screens.

The recently redesigned Market client introduced an interactive carousel that features promoted apps and games relevant to the current page. The carousel lives in the main navigation area and allows the user to quickly browse the promoted content and view concise information on the specific app. In portrait mode, the carousel takes roughly 40-45% of the screen height (depending on the screen resolution), while in landscape mode it takes the left half of the screen. The landscape mode is, in my opinion, a major step forward in improving usability and content placement, but we’ve introduced a usability regression for the home screen in portrait mode, especially for smaller QVGA screens.

Take another look at the screenshot – as you can see, the list of featured apps is scrolled below the carousel, while the carousel itself is a static element that is anchored to the top edge of the screen. While you can see slightly more than four full app listings on higher end devices, this resulted in poor usability on smaller screens – the scrollable area was too small, showing only about two app rows at a time.

As noticed by Al Sutton, we have addressed this issue in the last few weeks – the carousel now scrolls with the rest of the screen. If you’re not interested in flipping through the promoted content, you can quickly scroll it away and enjoy the full-height scrolling of the featured content.

In the original implementation, this screen had two child views – the “green goblin” header and the list of featured apps. The views were positioned with a custom layout that set custom padding on the list’s header view in order to provide correct (and screen-specific) overlap between the two views, while still allowing the list header to fully show when the viewport is at the top of the list. The carousel component lived outside the list and had its own handling of touch events to process selection, scrolling and flinging. And now we wanted the carousel to be scrolled with the app list.

I’ve mentioned this a few times before, and it’s worth mentioning it again – do not nest scrollable views. Doing so will lead to unpredictable dispatch of scroll events, mostly due to processing motion events that cross the boundary of the nested scrollable child. The ListView component is a scrollable view, and so wrapping the carousel and list in a ScrollView was not an acceptable solution. Instead, we decided to out the entire header (with the title, carousel and navigation buttons) as a header view of the list. This worked quite well, with vertical scrolls being correctly processed by the framework. However, processing touch events on the carousel was very flaky.

We have a custom onTouchEvent handler in the carousel view that detects horizontal motion and starts scrolling the content (and flinging it on ACTION_UP if the velocity is above the threshold). As long as the touch path was horizontal, our handler was getting the motion events and processing them. However, once the touch path sloped just a little, the handler was not notified – and instead the entire screen started scrolling vertically. This was due to the order of event processing – in this case, the parent list view has its own touch handler that detects vertical motion. All in all, we traded one usability problem (smaller scrollable area) for another (flaky processing of carousel scroll gestures). As luck would have it, our framework people (Romain Guy and Adam Powell) were on a holiday break, and we spent a few days trying to subclass the ListView and override the dispatchTouchEvent and onTouchEvent, detecting different scenarios and redispatching the touch events directly to the carousel view if necessary.

After a few iterations we got some ugly code that worked reasonably well for most cases, but we certainly didn’t feel very comfortable in putting such a hack into the production environment given the breadth of platform versions and device variety that we need to support. Once Adam came back from the vacation, he took a quick look at the code and pointed out a much simpler way – use the ViewGroup.requestDisallowInterceptTouchEvent() API. This is exactly what we needed – a way for a child component to tell its parent hierarchy to stop processing touch events. And the best thing (as documented in the method Javadocs) is that you don’t need to reset this state – it is automatically reset by the parent on the up / cancel events. So this is what we do now – a motion event that crosses the vertical threshold of the list before crossing the horizontal threshold of the carousel is still handled by the list. But, if the motion event crosses the horizontal threshold of the carousel first, we call getParent().requestDisallowInterceptTouchEvent(true). As long as the touch stays within the screen bounds (doesn’t to to the bezel), the move events are being delivered to the carousel. The vertical part of those events is being ignored by carousel, so that you can freely cross the bottom edge of the carousel into the list and still operate the carousel.

If you’re running the latest version of the Market client (2.3.3) you would notice that the carousel still displays a drop shadow along its bottom edge. This is a rather unfortunate UI omission, since the presence of drop shadow elsewhere in the Market client indicates that the rest of the content is scrolled below the matching view, while that view remains statically anchored to the screen. This will be addressed shortly to look like this:

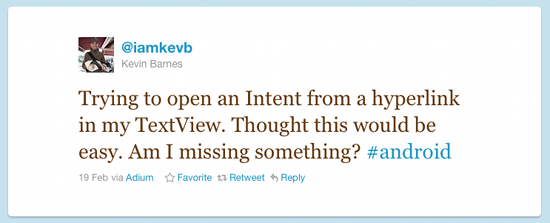

This tweet from Kevin Barnes crossed my stream last Saturday:

He posted the solution overview shortly thereafter, but i thought i’d summarize the different ways to display and handle hyperlinks in Android.

The core TextView component provides a nice range of features that make it a prime candidate for displaying hyperlinks. If your text and hyperlink address are static, the simplest way would be to define a string in your resource file. The string can contain the any number of embedded links, for example:

<string name="help_center">Visit the

<a href=\"http://my.company.com/help\"\>Help

center</a></string>

Now, you can either call setText(R.string.help_center) API or simply point to that string from your layout XML:

<TextView android:text="@string/help_center" ... />

At runtime, the framework will find the matching string (which can be in a localized folder), convert it to a properly formatted representation and register a click listener to launch the browser to view the associated link. There are two more things that you should do. First, use the android:textColorLink attribute to control the color of the link elements. Second, locate your TextView when the activity is created and call setMovementMethod(LinkMovementMethod.getInstance()) on it. This will allow users to navigate your links with a navigation ball, d-pad or any other focus traversal aid.

Let’s take this a step further – what if the link itself or the surrounding text are dynamic? Here, you can use the TextView.setText(CharSequence) API where the parameter is constructed dynamically based on your specific application logic. However, there is an additional step to do before calling that API. Once you have constructed the string – with one or more hyperlink segments in it – call Html.fromHtml(String) method. This will properly delineate the link segments and register the click listeners.

Note that up until now i haven’t addressed the original question posted by Kevin. Opening the hyperlink address in the browser might not be the optimal solution for all cases. You might not want to transfer the user to a full-screen browser, preferring to display the content in a floating dialog. Or perhaps you need to put additional controls around the hyperlink content. Or perhaps you don’t have any hyperlink content per-se, but rather need to run some custom logic on activating that segment (be careful though not to diverge too far away from the well-known pattern of hyperlink handling).

If you want to attach a custom listener to be invoked when the user activates the specific text segment, you will need to do the following:

- Create an instance of SpannableStringBuilder.

- Use the different append and insert methods to create the text content. Note that here you’re not going to create any explicit a href spans.

- For every “hyperlink” span, call the setSpan() API as shown below.

- Call TextView.setText(CharSequence) API, passing your instance of the SpannableStringBuilder to it.

- As before, call TextView.setMovementMethod(LinkMovementMethod.getInstance()) to enable proper focus traversal of your custom spans.

Here is an example of specifying and configuring a custom span:

SpannableStringBuilder stringBuilder = new SpannableStringBuilder();

stringBuilder.append(leading);

stringBuilder.append(middle);

stringBuilder.append(trailing);

stringBuilder.setSpan(

new ClickableSpan() {

@Override

public void onClick(View widget) {

// handle span activation (show dialog, ...)

}

},

leading.length(), leading.length() + middle.length(),

Spannable.SPAN_EXCLUSIVE_EXCLUSIVE);

myTextView.setText(stringBuilder);

Last Friday we announced a significant update to the Android Market client. A whole slew of features went into this update (and many more are to come), and this week the pixel geek in me will be talking about the new visual design of the application. Here’s a quick recap of the first three posts:

Today i’m going to cover a few miscellaneous bits and pieces. As they say, the devil is in details, and every single bit mentioned in this post is a small step towards improving the user experience and overall aesthetics of the application. I should note that these bits aren’t strictly necessary from the purely functional perspective – and are quite time-consuming to get right. But if you want your app to be less ass and more class, read on.

First, let’s take another look at the home screen of the new Market client in the portrait mode:

There’s a whole bunch of visual information that we put in the header section – market-bag icon, market title, search button, carousel, title / rating / price for the fronted app and the navigation buttons. This content can be roughly divided into three sections – the title bar, the carousel and the navigation footer. Following an established UX practice, we want to add some visual separation between the three sections. The separation between the title bar and the carousel is achieved by scaling down and fading thumbnails that are close to the edges. This creates extra vertical space directly below the market-bag icon and the search button. What about the separation between the carousel and the navigation footer?

Here we cannot “rely” on the vertical white space below the outermost thumbnails – that space is negated by a rather long row of views that display the title, rating and price for the fronted app. Instead, the design pushes the middle navigation button down towards the curved header edge. This effectively arranges the navigation buttons along the bottom edge of the container and adds extra vertical space above the middle button. Let’s take a closer look at the actual bounds of these three buttons:

How was this achieved? Here, we extend a LinearLayout with horizontal orientation, giving each button zero width and equal weight. This ensures that the buttons are perfectly placed along the X axis. We don’t override the onMeasure and rely on the parent’s implementation to compute the correct measured width and height. However, we do override the doLayout:

- Call the super implementation so that it can compute the final left and right bounds. We’re not going to change those.

- Compute the height of the curvature area. As mentioned before, this value depends on the pixel size of the screen and is only known at runtime.

- For each visible child button, take two reference points. One is at 25% of its horizontal span, and another is at 75%. For each reference point, compute the matching Y position on the curvature arc. The min of these two Y values will define the bottom bound of the button.

Why choose 25% and 75%? Take a look at the “Apps” and “My apps” buttons in the screenshot above. Each one extends all the way to the container edges, and computing the Y offset based on those would result in unnecessarily high bottom bound. Here you can say – what if the button text is very long and spans the entire button width? There are a couple of other settings at play here – left / right padding and scaling down the text size (will be detailed below) that keep the texts from overlapping the curved arc.

Next up – text scaling. As mentioned in the previous entries, Android devices come in a wide variety of screen sizes and densities. In addition, if you target international markets, you should properly localize your strings. So, unless you want to see your fine-crafted UI looking (say it with me) like ass on a lower end device running under one of the more expressive European languages, you’ll need to make sure that the texts comfortably fit within their intended bounds.

Marking the view with marquee ellipsizing and flipping the selected bit to true is one option. That would enforce auto-scrolling texts that do not fully fit in the padded bounds. This is simple, but quite distracting. If evolution is to be believed, even before our ancestors were hunters, they were prey to large clawed animals. If you detected a suspicious movement in the nearby bushes, you were supposed to run away like a little girl. Or stand there and be eaten like a real caveman. Anyways. Getting back to writing pleasing UIs. User’s eye will be instinctively drawn to scrolling content – which is one of the reasons why we set a relatively large auto-advance interval on the carousel. Now imagine us scrolling the texts on all three navigation buttons at the same time. That’s not really good. They are navigation buttons, not the main content. Unless you’re absolutely sure that this is what you want, you should not marquee anything on the screen. So another option is to scale down the text size based on the available space.

Here is one example:

This is the header section of the new app details screen. We have a nice drop shadow for the thumbnail, the white texts and extra nice vertical alignment of the thumbnail and the control column to its right (both top edge and right edge). If you look closer at the two buttons, you will see that the regular / bold style is not the only difference. The second button also uses a slightly smaller text size to fit the longer string and prevent some of the characters from overflowing into the padding. This is fairly easy to achieve:

- Extend the Button class. In the constructor, call getTextSize() – that would be the default text size, and divide it by the screen density. Store that value.

- In addition, override the onLayout method. The following bullets are relevant to the context of that method.

- Get the measured width and height (for restoring those values later on).

- Starting from the saved text size, call setTextSize() and measure(MeasureSpec.UNSPECIFIED, MeasureSpec.UNSPECIFIED). Assuming that the button is defined to be singleLine, you can now call getMeasuredWidth() to know how many pixels does the button need (including the padding) for the specific text size.

- As long as the measured width is less than available width – use the left and right parameters passed to onLayout, decrease the text size and repeat.

- Once the you found the max text size that makes the text fit in, call setMeasuredDimension to restore the “original” measured width and height.

And here’s another example:

Here, we have rather long Korean strings for the tab titles. The algorithm above can be applied here as well to scale these strings to completely fit on one line, but the end result will be quite unreadable. Instead, the tabs allow two lines of text, and the algorithm is slightly different:

- Call setMaxLines(2). Call setLayoutParams with a LayoutParams set to WRAP_CONTENT on both axes.

- Now you want to compute the two-line height of the view given the specific width limitation and see whether it fits in the available height. This will also cover the case where the text can completely fit on one line with the starting text size. Call measure passing the MeasureSpec.makeMeasureSpec(availableWidth, MeasureSpec.EXACTLY) for width and MeasureSpec.UNSPECIFIED for Y. Now call getMeasuredHeight() and compare to the available height. If it fits, you’re good to go. Otherwise, proceed.

- Now call setMaxLines(10). This is an arbitrary setting, but it’s important that the value is larger than 2.

- Starting from the initial text size, call measure with the same values as above. Check two conditions – that the measured height is less than the available height and that getLineCount() is at most 2. The second condition will prevent displaying more than two lines of text – even if three (or more) will fit in. Here, we prefer to show two lines at a smaller size than three lines at a larger size – to maintain visual balance across all three tabs that may have radically different text lengths for their titles.

Now let’s talk about padding. In landscape orientation we display content side by side – the carousel / overview go on the left, and the vertical listing goes on the right. Here is an example of such layout:

We want to prevent the curved right edge of the info section from partially hiding some of the content in the vertical column to its right. This can be achieved by setting the left padding based on the horizontal span of the overlapping area. As mentioned before, we want the section headers (fading vertical gray gradient) to fully extend below the arc – effectively preventing us from setting the left padding on the entire column. This means that we set the left padding on each child view. However, some of the child views may have their own left padding defined in their layout XMLs – for purposes of balance, alignment or hierarchy.

Our first attempt was to call getPaddingLeft(), add our extra padding and then call setPadding(). Surprisingly simple, but not quite working. The layout pipeline can make several passes at measuring and laying out the views, and if you add extra padding on each such pass, you will end up with too much padding. There’s a simple workaround:

- Create a res/ids.xml file and add an item with type=”id” and some name and recompile your project. You should have the new R.id.yourName constant.

- Every time you need to tweak the padding, call getTag(R.id.yourName) and check if it’s null. If it is, get the current left padding and store it with setTag. If it is not null, then the current tag value is the original left padding.

As with everything else, adding animations should be done with restraint. It’s very easy to go over the top and make everything pop, scroll, slide, fly, cross fade and in the process cause great deal of misorientation, distraction and frustration (which, unless you’re selling shady prescription-only drugs or cheesy wedding videos is not a good thing). In the new Market client you should see only two types of non-user-initiated animations: auto-advance on the carousel and marquee scrolling of long app titles. The auto-advance is scheduled to run every 20 seconds, and is bumped to 40 seconds once the user starts interacting with the carousel. It goes down to 20 in decrements of 2 as long as there is no user interaction. This allows us to show that there is more than is currently visible without overloading the screen too much. Long app titles should be scrolled in order to see the full application title without going to the details page.

However, some aspects of the new UI deserve an extra dynamic facet to guide the user through the complete flow.

This is how the new application details page looks in landscape mode. Note the “More” button in the description section. Application descriptions can be quite long (especially with the newly added “recent changes”). The long descriptions effectively push the screenshot section down and result in a large amount of text displayed on the screen by default. Our interaction designers felt that the screenshot section deserves to be at least partially visible above the fold, with the description section collapsed by default to three lines. Note the nice fade-to-white transition on the last line of the description section, hinting that there is more content, and ending in the “More” button. Tapping the button expands the description to show the full contents – in a nice and smooth transition. We felt that this short (around 300ms) transition helps to guide the eye between the two views without being too annoying (==long).

The implementation is quite simple and works well even on older devices going all the way back to 1.6 (looking at you in disapproval, Streak). The vertical column on the right is a LinearLayout with vertical orientation. When the “More” button is tapped, we initiate an animation. On every animation callback, we call getLayoutParams() of the description view and change the height attribute based on the current animation position. This is followed by calling requestLayout(). The framework takes care of the rest – detecting that the child view layout params has been modified and going to the parent (our LinearLayout) to re-layout all its children.

The same transition sequence happens when you click the price button in the info section. The content on the right is replaced with the permission list which slides from the top edge, guiding the user’s eye to connect the tapping of the button and the content change on the screen.

There’s a whole lot more going under the hood and this has been just a small glimpse into the redesign of the Android market client which has been a truly collaborative effort across our designers, developers, testers, dev rel, product management and the guy sitting in the basement with his red stapler. If you’re interested in joining us and seeing your app user base growing by 300,000 people every day, let us know.

Last Friday we announced a significant update to the Android Market client. A whole slew of features went into this update (and many more are to come), and this week the pixel geek in me will be talking about the new visual design of the application. Today it’s time to dive into the mechanics behind the swooshy header. The new green header is used in all Market client screens, creating visual continuity throughout the various browsing and purchasing flows. It has a whole bunch of different gradients and highlight streaks, but there’s one important thing to notice – the visuals are the same no matter the size of the header or the orientation of the device. Here is the new header in home screen under portrait mode:

And here is the header of the same screen under landscape mode:

Note how the long diagonal highlight streak that starts around the top-left corner and goes towards the bottom-right corner always intersects the curved edge – bottom in portrait and right in landscape. Let’s see the header in the portrait category listing page:

There are a couple of things worth noticing. First, the visual design maintains the connection to the main browsing pages by adding a curved bottom edge to the tab strip. Second, note how the main header visuals are maintained here without being vertically squished. The long diagonal highlight streak still intersects the curved edge, but much closer to the left edge, and you don’t even see the double converging highlights that run in the bottom part of the taller header. And here is the same header for search results (also used in my apps and all the purchase pages):

With even less height, squishing the full visuals would look very bad; instead, we only show some of the highlight streaks.

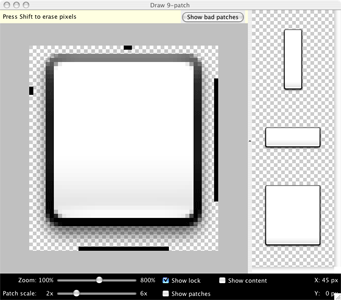

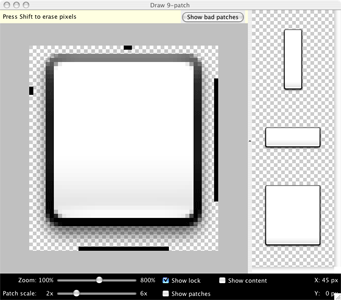

And now the fun part – how is this implemented? It’s highly recommended to always consider using nine-patch images as your first choice. It allows you to separate the visual styling from the application functionality, skin controls of different sizes in a consistent manner and take advantage of hardware acceleration (when available) since the vast majority of the system controls are styled using nine-patches. Is this what we’re currently using for the new Market client? No. Let’s see why.

Nine-patches are great if you have visual areas that are “stretchable”. Take a look at the images in the official documentation:

Nine-patch is just a 3*3 grid. The four corners are not scaled at all and are well-suited for rounded corners and varying drop-shadows. The top and bottom pieces are stretched horizontally, while the left and right pieces are scaled vertically. Finally, the center piece is scaled along both axes. This means that if you place any non-linear gradient or path in one of the non-corner areas, it will be stretched. Looking back at the target visuals of the new green header, you can see that there is nothing that can be stretched without ruining the visual appearance. While you can stretch most of the gradients, what about the highlight streaks? Scaling them up or down would result in blurry or pixelated paths. What about the curved edges? As mentioned in the first installment, the actual arc curvature depends on the pixel size of the screen, and scaling a curved anti-aliased path would result, once again, in either blurry or pixelated visuals. Less ass than what we had before, but ass nonetheless.

So instead, we’re drawing the new header visuals in code. There are no images, just a whole bunch of trigonometry, geometry and a few selected Canvas calls. The next screenshot shows a rough analysis of the swooshy header

Here we identify a number of different areas, each one with its own contour and gradient, and a number of highlight streaks, each with its own path, thickness and gradient. I could probably write another 3-4 blog entries documenting all the pixel-level details of the implementation; join the team to see the code. Just a few points worth mentioning:

- Never ever ever allocate new objects in your custom layout or draw methods, especially if you’re doing any type of animation. Allocating lots of small objects makes garbage collector sad and your animations jerky.

- Call setWillNotDraw(false) in the constructor of your custom view group that implements the onDraw(Canvas). Otherwise your custom drawing will not be called. If your custom view does not extend the ViewGroup, no need to call this method.

- Canvas.clipPath(Path) is your friend for any non-trivial custom painting code. Surround it with Canvas.save() and Canvas.restore() so that you don’t need to worry about subsequent graphic calls on the Canvas object. But make absolute sure that they match – if you call Canvas.restore() one too many times, it will affect the visual appearance in most unpredictable ways. You can also use a more reliable Canvas.restoreToCount() – thanks to Romain for the tip.

- If your clip path contains diagonal lines or arcs and you then call Canvas.drawPath when the paint style is FILL, you will end up with aliased edge (diagonal or curved). Instead, you will need to compute the clipped path yourself (brush up on your trig). Don’t forget to call Paint.setAntiAlias(true). This may be less noticeable on higher-density screens such as Droid X or Nexus S, but is extremely visible on lower end hardware such as G1 or Flipout.

- Drop shadows that follow custom paths are tricky. Our design calls for a translucent drop shadow that follows the curved arc. After trying a number of options, with Paint.setShadowLayer and RadialGradient among them, the most performant one turned out to be drawing a series of arcs. The arcs start from the thickest stroke with the lowest alpha and progress towards the thinnest stroke with the highest alpha. There is no best option that fits all requirements. It depends on the specific visuals that you’re looking for and how heavy the performance aspect of each specific implementation is.

- Gradients that use translucent or transparent colors should use the RGB values that match the background color (more info here).

- Don’t use direct pixel values. Multiply all such values by the Context.getResources().getDisplayMetrics().density.

- Don’t use hard coded colors. Extract them to res/colors.xml and load them once with Resources.getColor().

- Math is your friend. Don’t be afraid of it.

- Never ever ever allocate new objects in your custom layout or draw methods, especially if you’re doing any type of animation. Allocating lots of small objects makes garbage collector sad and your animations jerky.

That’s it for today. Tomorrow i’ll talk about various random bits and pieces.

The recently redesigned Market client introduced an interactive carousel that features promoted apps and games relevant to the current page. The carousel lives in the main navigation area and allows the user to quickly browse the promoted content and view concise information on the specific app. In portrait mode, the carousel takes roughly 40-45% of the screen height (depending on the screen resolution), while in landscape mode it takes the left half of the screen. The landscape mode is, in my opinion, a major step forward in improving usability and content placement, but we’ve introduced a usability regression for the home screen in portrait mode, especially for smaller QVGA screens.

The recently redesigned Market client introduced an interactive carousel that features promoted apps and games relevant to the current page. The carousel lives in the main navigation area and allows the user to quickly browse the promoted content and view concise information on the specific app. In portrait mode, the carousel takes roughly 40-45% of the screen height (depending on the screen resolution), while in landscape mode it takes the left half of the screen. The landscape mode is, in my opinion, a major step forward in improving usability and content placement, but we’ve introduced a usability regression for the home screen in portrait mode, especially for smaller QVGA screens.