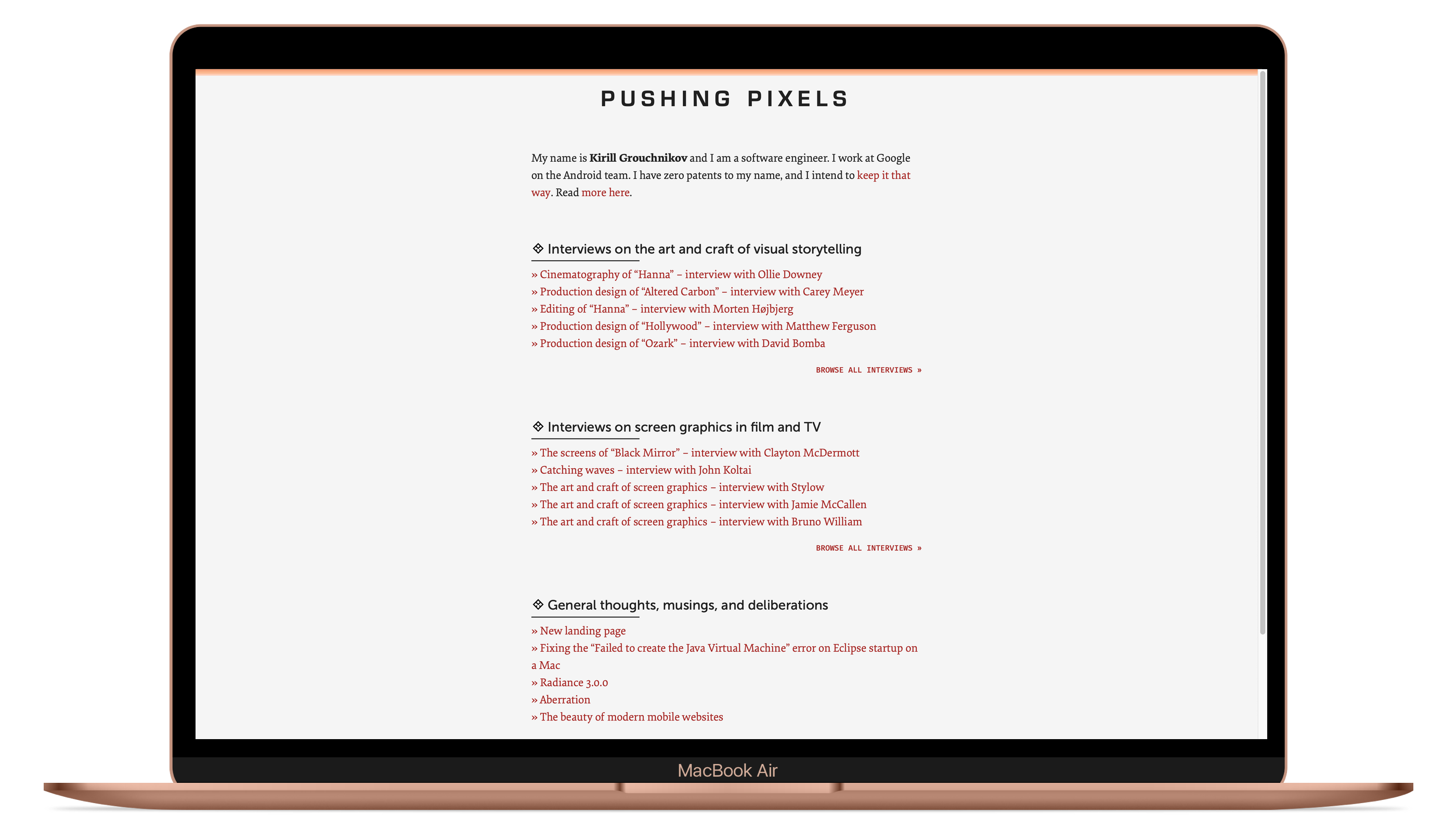

If you read this in the RSS reader, you won’t see any difference. But if you hit the main landing page in the browser, you’ll be greeted with the new layout:

The new structure follows the changes in content in the last few years. It’s been a bit awkward to have a landing page that listed the last four posts, whatever those might be – interviews, announcements on Radiance, or random musings. I’ve tried addressing that by adding separate landing pages for the interviews, but that wasn’t readily discoverable.

Now, the main page of this site is structured around three major content areas:

- Interviews on the art and craft of visual storytelling – these are interviews with cinematographers, production designers, art directors, etc on how films, TV shows and episodic productions in general are made.

- Interviews on screen graphics in film and TV – these are the FUI (fantasy user interfaces) that we see not just in big sci-fi blockbusters, but pretty much in any contemporary production these days.

- Everything else – these are occasional updates on Radiance, some tips on coding, or general musings on whatever has been on my mind lately.

The great thing about this new structure is its flexibility. I can add more sections as my interests change. I can rearrange the sections, or display more entries in each section. There’s some space up top for a short intro. Hope you like it.

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my pleasure to welcome Ollie Downey. His work in the last few years can be seen in productions such as “Electric Dreams”, “Harlots”, “Britannia”, “Temple” and others. In this interview, Ollie talks about the cinematography of the second season of Amazon’s “Hanna” that takes us all across Europe, as well as diving deep into a whole new training facility known as the Meadows.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today

Ollie: I always intended to study Fine Art, but had a last minute change of heart. I loved painting but ultimately it was too isolating – I enjoy being around people too much to be standing at an easel all day. I have vivid memories of catching “North by Northwest” on TV when I was very young, and being mesmerised by the imagery. I also spent a big portion of my early teens discovering all those great Coppola and Scorsese films you do at that age. After College a pal got a job as a 3rd AD on a low budget Feature, and they needed a Runner. I really enjoyed it, and just being on set cemented my interest in Camera and Lighting. From there I worked my way up through the Camera Department, always DPing little low budget Shorts and Promos on weekends. After about 10 years the DPing took over from the assisting.

Kirill: When you talk about what you do for a living with somebody who is not in your industry, how difficult is it to convey the complexity of what it is that a cinematographer does?

Ollie: I think most people believe you stand there with a camera on your shoulder all day. I tend to say that I’m responsible for the lighting and framing of the show, working with the Production Designer to set the mood.

Cinematography of “Hanna” by Ollie Downey.

Kirill: Between finding the right artistic expression to tell the story and the technical side of things (lenses, camera bodies, etc), is one more important than the other for you?

Ollie: It’s absolutely the artistic expression of the script that is the most important to me. I think it’s good to forget about the technical aspect altogether until you’ve got your head around the script. Once you understand the story and characters, your visual references fall into place and the technical approach follows.

Kirill: Looking at some of the work you’ve done in the last few years, it spans different genres and periods – from “Temple” to “Electric Dreams”, from “Hanna” to “Harlots”. Is it your intent to explore different genres?

Ollie: Absolutely. I think it’s really important not to repeat yourself. One of the most satisfying parts of the job is creating the look in Prep. Building a library of references and letting that dictate your camera package, lens choices, framing and lighting style.

Cinematography of “Hanna” by Ollie Downey.

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my delight to welcome Carey Meyer. In this interview he talks about his approach to designing his productions, the changes in the world of visual storytelling since he started in the field in the early ’90s, embracing accidents, and how much may change on the other end of the current Corona break in the productions. Around these topics and more, Carey looks back at his earlier work on “Firefly” and “Buffy the Vampire Slayer”, and dives deep into creating the lavishly intricate worlds of the first two seasons of “Altered Carbon”.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Carey: My name is Carey Meyer and I’m a production designer in the film industry. I’ve done a couple small features, but I mostly do episodic television, and it’s been quite good.

Going back to how it started, I was always an artist. I found myself enjoying design and architecture, and I went to a school of architecture – a program called “design studies” that had a broader reach compared to a bachelor of arts degree. We studied all fields of design – environmental design, graphic design, architecture, product design, etc. We got a broad concept of how design processes could be applied to all those different fields. We were learning a process that wasn’t dedicated to one specific thought within design. I enjoyed breaking it down into those specific fields, focusing on training and understanding them.

In that college we had a film club, where a bunch of friends and I would do theme events for the school of architecture. We would typically base them off of a film like “Brazil” or “Blade Runner”, and that was my first spark in film. I started seeing it as a field that requires a lot of design, not just production design but also cinematography design, direction design – in a way, it’s all a design process.

Obviously, I fell into mostly production design, although I have directed quite a few episodes of television as well. And having been at the helm on a few episodes of television made my design process much more specific and edited. You have a much more nuanced idea of what is important as a designer. You are able to have those conversations with directors, to know and understand that they are going to take a specific nuanced tone with a scene that might be the crux of the entire tone of the whole piece. It might be a feature film, or an episode within a series.

Production design of “Altered Carbon” by Carey Meyer, the view going “up into the clouds” of Aerium in Season 1.

Those conversations are critical in television. You’re trying to create with a multitude of directors and multiple cinematographers. What is the tone of the piece? You’re trying to design and build things in an efficient way. You’re breaking down a script and deciding what’s going to be a location, or how you’re going to design this to match with the location, or if it’s going to be built on stage. There’s a myriad of reasons why you would do things on stage vs on location. A lot of it has to do with schedule, especially in television. You’re trying to marry bits and pieces of the puzzle together, and so you might edit the script a little bit to get those pieces to fall within a schedule in a construct that makes sense for the production.

As a production designer, that’s one of my main focuses – to start having those conversations. I’m talking with the director and the showrunner, who’s really the main steering partner, and we discuss that specific tone that holds for the rest of the series. Then it evolves and morphs into other things, and that is a lot of fun. The tone of the piece that emerges from those conversations ends up affecting what you build and what you design.

Kirill: When you talk with people outside of your field, is it easy or hard to explain what you do for a living?

Carey: It’s hard to give them the nuance. That’s what this position is – it is nuanced. I’m not just trying to design a pretty room. I’m trying to have the conversation about what room do we really need. What does that mean to you? How does it fit together with all the other pieces? You can’t just go ahead and start designing a room.

We have the conversations about color and lens choices. How dark is it going to be? What pieces do we really need to have in there? What is our critical wide shot, and what’s the focus on that scene? Can we build a wide shot that is meaningful so that we can then go in and create a lot of cinema within? Maybe we don’t necessarily need the whole ballroom. Those are conversations that I get excited about. When you start having that conversation, you are immediately cutting out half the work, because now you’re not having to necessarily create the whole thing.

Of course you do have the bigger environments, especially on TV series, that will play for the entire show. Those are well thought out and fully realized. But you also have the bridges between those scenes, and those structures can have more plasticity to them. You don’t need to fully structure those bridges. That all comes down to the cinematography, the edit, and the tone that the director is going to take with those scenes. You build the trust with your director that they are going to follow through on the idea they have in their head, be it a storyboard or not. And of course, you find great stuff on the day too.

I hate the old adage of the smoke and mirrors, but using those gags and gimmicks to create fantastic images does have a big part to play in the process.

Illustration of the Psychasec Lab for Season 1 of “Altered Carbon”, courtesy of Carey Meyer.

Production design of “Altered Carbon” by Carey Meyer, Psychasec Lab in Season 1.

Kirill: Do you find that much has changed since you started working in the early ’90s? If I had a time machine, and I brought you from 1990 straight to 2020 (ignoring Corona of course), would the young you feel at home in 2020, or would you say that things have changed significantly?

Carey: I’d definitely feel at home, and that rings especially true in television, because you cannot afford all the CG that might happen on a big feature film. And even on a big feature it has to be conceived, and everybody has to understand what those pieces are, down to costume and props. Everybody has to understand what that environment is, and at some point there’s going to be something that’s built, and it can’t just be random.

So the creation of all that imagery is really what’s important. Another important thing is that everybody understands what it is. From a production designer’s standpoint, you might leave on the table huge swaths of a script that are going to end up in a CG environment, but you still want to have a good understanding of what those environments are, so you can build and relate your built world to it and vice versa.

“Altered Carbon” was a terribly ambitious world that we were trying to create, and the size of the budget was absolutely the largest I’d worked with. I knew at that time that it was going to be the most intense design process, figuring out all those CG elements, and figuring out what that world needs to look like. That needs to happen so that you can communicate that to the entire CG department, so they would all get on the same aesthetic and start integrating that world that was beyond the shot lens, and incorporated into what we did shoot on camera. But you still have to build as much environment as you can, so CG can get even further and bigger for the storytelling.

If they end up creating all the background in most shots, then that’s where your money’s being spent. The first season was 10 episodes, and we created a large part of that world. We built a 300-foot long street to shoot on. We had the ability to make it feel like it was a different place in different scenes. We were more successful with certain versions of it, maybe less with others, but it was all one world. And we were able to control it and push the envelope on how it can look.

If you were trying to do a lot of that work on location, you’d end up with CG removing all kinds of signage, and adding bits and pieces to try to make it look not contemporary. And we didn’t want to waste our money doing that. We’re talking about a TV schedule. We were on a series schedule, still shooting on location all the time. It gets problematic, complicated, and expensive. We did a good portion of on-location exterior shooting to help extend that world, but we needed to have a real base station of the world that we knew we could always fall into.

Production design of “Altered Carbon” by Carey Meyer, exterior of the Raven Hotel in Season 1.

Continue reading »

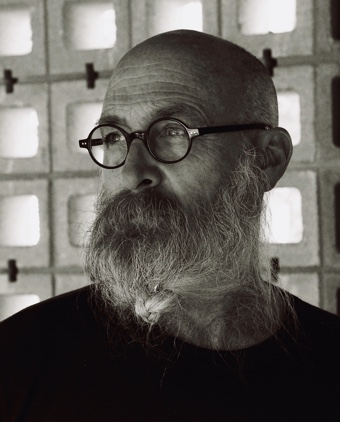

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my pleasure to welcome Morten Højbjerg. In this interview he talks about how he started in the field of editing, what changed and what didn’t in the transition of editing from physical to digital tools, his approach to “emptying the frame” and keeping the viewer’s attention, and serving as the final bridge between what was shot and what we the viewers see. Around these topics and more, Morten dives deep into what his work on the first two seasons of Amazon’s “Hanna”.

Photo by Bjørn Djupvik

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself, and how early (or maybe late) you knew you wanted to be a part of the visual storytelling field.

Morten: I’m Danish and I grew up in this little village in the countryside. Growing up, I didn’t know anybody who was even remotely in the film industry, so I never imagined that I would have anything to do with movies. It wasn’t even within range of reality. I don’t think it even ever crossed my mind that there was such a thing as editing.

When I was a teenager, I moved to Copenhagen. I didn’t really know what I wanted to do with my life, but by some weird coincidence I got hired as a runner in a production company that made commercials. It happened to be around the time when the whole digital shift was coming, old-school physical editing tables to digital editing, and this company that I was a runner for, invested in one of the first AVIDs in Denmark – which is now one of the most common digital editing systems.

Back then, there was nothing on screens in my life. I didn’t own a computer, I didn’t have a mobile phone. I remember the first time the whole thing was set up and it was playing something, and it just blew my mind to watch video running on this computer screen. It was magic. I had never seen anything like that. It was incredible.

Anyway, they bought one of those, but no one really knew what to actually do with the thing. I was really fascinated, and hating my job as a runner, I started to dig into it. I read the manual, and after doing my runner duties throughout the day, I spent all my evenings learning and studying this fantastic machine. Before long I started being an assistant for some of actual editors. In my free time and on weekends I was cutting stuff on my own, making short films out of all the commercials that were in the archives. Those were random, weird short films out of washing powder commercials cut together with car commercials etc. That was my way in.

As soon as I saw this thing and started to understand a bit about what it was, looking over the editors’ shoulders and understanding the magic of this job, I knew that this was what I was going to do for a living. It was perfect, and I have not done anything else ever since.

Kirill: Looking from the outside in, it was interesting for me to see how reluctant some people were to transition from film to digital. Do you think it was a smooth transition, or were there “pockets of resistance”, so to speak?

Morten: Of course there were pockets of resistance for a while. Editing on Avid is radically different to editing on a Steenbeck table, and I guess it took a few years to change the habits and methods for a lot of people. After my time at the production company I went to the National Danish Filmschool for four years. Back then they still had the old Steenbeck tables standing around collecting dust in the corners. I insisted on using them for my short films, and I made my midterm film on the Steenbeck. It was so complicated, and the whole physicality of it was incredible. You had to be so organised. I spent hours and hours with my head in the bin, trying to find little pieces of film that I had cut out but then later wanted to put back in. On a Steenbeck you needed to think about what you were doing in a completely different way. You needed to have a plan before you started doing anything. It took hours to make changes, with so much looping and rolling the film through the whole thing. I’m really grateful that I arrived at the scene in time to experience that. I think there is a lot to learn from that approach in terms of the thought process that goes in to the editing of a film.

One interesting aspect of editing in digital versus film is that it didn’t actually become faster to cut a feature film than it was back in the day with Steenbeck tables or Moviolas. You might think it would be but it really isn’t.

Kirill: Is it because the art of editing hasn’t changed, and it’s still as challenging to find the right artistic expression? Or maybe is it because you have more digital material to work with because the camera keeps on rolling?

Morten: I think it’s a combination. The fact that you can roll now gives us much more material to work with than what it used to be when it was like a 35mm camera. With film, when you pushed the “On” button, you could hear the money roll out of it [laughs] – and now it’s not a big thing anymore. You record to a card and then reuse it

But another thing is that the thought process has not changed. That still takes a certain amount of time from when you see the material the first time, regardless of how much there is. You take that material on a journey to a finished film. It’s still a physical journey, but it’s also a mental journey and that takes a certain amount of time before you can conclude it.

Somehow I also think there is a danger in digital editing actually. Because it’s so easy and you can make endless copies and versions effortlessly, it has become easier not to properly think about what you are doing. It has become easier to get lost.

Kirill: On a more technical side of things, how obsessed or perhaps paranoid are you about losing material on those digital cards or disks? Is there more fragility to it compared to the old days of film?

Morten: That is true, but it’s always been like that on film as well. If the assistant did something wrong and exposed it to light, it was gone. Back in the film days, you would go to the lab after the end of the daily shoot, and lock the film roll into a special closet with all sorts of codes and keys. Whatever it is, a film roll or a flash card, it often represents a huge amount of money. A whole day of production that you may not able to replicate if it’s gone.

Kirill: Do you think there’s ever going to be such a time as a disc big enough that it doesn’t need to be bigger?

Morten: It doesn’t look like that, does it? The resolution keeps going up, from 6K to 8K to now 12K. The drives needs to be bigger, and then everything grows simultaneously all the time. I don’t know if there will ever be a time when we can’t really tell the difference. Is it 50K? Is it 72K? I don’t know if the human eye has any limit like that.

That’s the thing about film, and why so many people maybe still love film. It’s a more organic thing. It’s not limited in these numbers. It’s a fluent thing that is, maybe, a better replication of how we work as organic beings.

Editing of “Hanna” by Morten Højbjerg, courtesy of Amazon Studios.

Continue reading »

![]()