In this second installment (part I here), it is my pleasure to talk with John Renzulli and Arissa Blasingame of Chicken Bone VFX about their work on the first three seasons of “Westworld”.

Kirill: A few years ago, “The Hobbit” trilogy tried to push HFR [high frame rate] with its hyper-realistic feel, and a lot of film critics where pushing back against that, arguing that film needs that “artistic” layer where the viewers don’t “need” to be right there in the middle of it. What’s your point of view on it? Is it fine that that pinky finger might be missing from one of those dead bodies way out in the background?

John: It needs to be layered, absolutely. It really depends on what we’re trying to do. For certain parts of entertainment world, that hyper-photo realism is essential. There you need that hyper frame rate with 8K level of detail and the focus on creating a feeling that it’s real.

John: It needs to be layered, absolutely. It really depends on what we’re trying to do. For certain parts of entertainment world, that hyper-photo realism is essential. There you need that hyper frame rate with 8K level of detail and the focus on creating a feeling that it’s real.

I think that in most of the entertainment platforms, and types of episodics and cinematics that we work on, you see that artistic layer that needs to limit some of that. Some of that comes from an old school love for film, and my personal favorite format is definitely 35mm. Because the celluloid itself is so responsible for helping create feeling and mood in the way that it was historically in the industry, to some degree that filmic quality needs to stay. It doesn’t mean that the resolution doesn’t get higher, and it doesn’t necessarily even mean that the image doesn’t get sharper.

But if you work with color, through careful analysis at the beginning of a project, talking about what resolution is required, and even working at the very end of the pipe to slightly degrade things to some degree – all of that can introduce that “filmic” quality that allow the viewer to have a specific response to the medium. Everybody sits in a slightly different place. Each creative we work with certainly sits in a different place there. But in most of the material that we work on, we find that there’s that artistic layer that somewhat limits the overproduction of something.

Sometimes it can be as simple as a creative choice, or it could be budget. Budget can also inform some of those decisions. More frames per second means more frames to render and more frames to fuss over. So, processes take longer and they inevitably get more expensive, so budget could inform some of that as well.

Arissa: When you’re trying to create something new with a director that has a vision that’s never been done before, you want to get it as close to real as possible. But sometimes there’s no bar to gauge that against. It depends on the task that you have been given, what that collaboration looks like, and where you get to with the final product.

Arissa: When you’re trying to create something new with a director that has a vision that’s never been done before, you want to get it as close to real as possible. But sometimes there’s no bar to gauge that against. It depends on the task that you have been given, what that collaboration looks like, and where you get to with the final product.

That’s always a little bit of a risk and a gamble. You don’t know how audiences are going to react to something that may be grounded in reality, but definitely has a fantastical side. It’s the risk and the reward of our industry. You can nail it or it might miss the mark, but it’s always a fun collaboration along the way to get to be that creative and work up something that the audience hasn’t seen before.

I’m sure that on “The Hobbit” they were trying something new and breaking the mold. And something like that is received differently across different audiences. And that then informs something in the future that can only get better with time. It’s an exciting spot to be in.

Chicken Bone VFX work on “Westworld”.

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my pleasure to welcome John Renzulli and Arissa Blasingame of Chicken Bone VFX. In this first of the three parts, they talk about where visual effects fit in the ever-evolving world of art and technology of feature films and episodic TV productions, the increasing expectations from and sophistication of modern visual effects, and finding the balance between the technical and artistic sides of what they do.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

John: I came into this field at a very young age. I’ve always wanted to be behind the camera, and to be an actor that did his own stunts, like Michael J. Fox in “Back to the Future”. After I did my first commercial, I realized that I loved green and blue screens and all the things that are meant to look realistic, but aren’t.

John: I came into this field at a very young age. I’ve always wanted to be behind the camera, and to be an actor that did his own stunts, like Michael J. Fox in “Back to the Future”. After I did my first commercial, I realized that I loved green and blue screens and all the things that are meant to look realistic, but aren’t.

When I was in college, that led me into post-production and editorial, and towards the end of my degree, I was deeply into VFX. That’s how I trended into the VFX community. Visual arts have always been interesting to me. I was always curious about how to get everything to be cohesive on the screen with the unified creative vision. I’ve always been interested in that process, and I’m always learning more about it. It continues to be very interesting to me to this day.

Arissa: I am quite the opposite. I didn’t know much about the industry at all when I was growing up in Florida. It was not really on my radar. After college, I moved out to Los Angeles and took an entry level job at the post facility, Nomad Editing. A few years in they started developing a VFX branch and I became intrigued by the creative process. Around the same time Johnny was looking for a producer at Chicken Bone, we connected, and the rest is history.

Arissa: I am quite the opposite. I didn’t know much about the industry at all when I was growing up in Florida. It was not really on my radar. After college, I moved out to Los Angeles and took an entry level job at the post facility, Nomad Editing. A few years in they started developing a VFX branch and I became intrigued by the creative process. Around the same time Johnny was looking for a producer at Chicken Bone, we connected, and the rest is history.

Kirill: How do you talk about what you do for a living? Perhaps some people consider VFX to be futuristic spaceships and robots shooting lasers, but on “Westworld” it’s about augmenting what was done in camera – for practical or budgetary considerations, and not necessarily something that is “out of this world”. Do people ask you why things at this level need to be done digitally in VFX?

John: Some people do, and sometimes it’s a function of collaborating with the creators. Budget included; you want to get a sense of what’s the right solution for this. We solve not only how it ultimately looks like in the end, but also how do we do the effects creatively. We talk about the evolution of that creative process. Before we talk about the creative visuals, we start with the creative strategy. This deep collaboration with the people that are offering the show is the heart and the soul of this company. It might be a big show or a small show, an indie project or a studio project.

Our heart and soul is geared toward high-level collaboration. That is what we do when we’re trying to figure out how we put the pixels on the screen. Every situation calls for something a little bit different, whether it’s a 2D or a 3D thing. We try to find out the straightest or the most obvious path, and if there isn’t an obvious path, we talk about how we can bite it off in chunks to make it a little bit easier in our own workflow.

Chicken Bone VFX work, progression from building models to the final layered frame.

Kirill: Do you feel that as the time passes, the evolution of technology at your disposal allows you to do more? Is there a limit to what needs to be done? Is there going to be a point in the near future where you will have exhausted the realms of what productions need, and there’s nothing to explore beyond that?

John: The technology is always pushing us and driving us forward. It allows things to be simple; it allows us to explore avenues or thought processes that we never would have explored before because the traditional tools would not allow our brains to think that way. If you take artificial intelligence or machine learning and you apply them to VFX, it’s a different mental path than something more traditional like getting rid of the green and replacing it with something that looks photorealistic.

In a way, the technology is always making things easier. But in no way I’m going to say that we’re going to hit our ceiling anytime soon. If anything, it will allow us to be creative more dynamically. It will allow us to get closer to the ultimate creator’s vision of a project, because we can get there much quicker, iterate more often, and create in a way that is a bit more dynamic in almost real-time. That is a level of integration that we haven’t really seen in the industry until very recently.

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my pleasure to welcome Carly Reddin. In this interview, she talks about working with multiple directors and cinematographers on episodic productions, what is involved in being a production designer, the current production landscape as the Corona-related restrictions are being slowly lifted, and what keeps her going. Around these topics and more, Carly goes back to her connection to the original movie on which she did set design, and dives deep into her work on creating the worlds of the second season of “Hanna”.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Carly: I was always artistic as a child, and I got interested in the theatre. I belonged to a couple of theatre groups, but I was always more drawn to the backstage aspect, as I wasn’t comfortable performing on stage. I just loved the magic of backstage, of creating worlds through set design, and the imagination that went into that.

After school, I was all set to go to Central Saint Martins to do the “Design for Performance” theatre course, but then I came across a course at Nottingham Trent University called “Design for Screen”. That summer I watched “Space Odyssey”, “June”, “Brazil”, and it opened up my eyes. I realised I could design worlds for film and TV for a job, and I was hooked.

So, I went to Nottingham Trent and did the degree there. The course leader from the National Film and Television School came to give a talk about their MA in Production Design, and I applied. When I was at that school, I was hoping the experience I was getting would lead to a job, and luckily one day I was invited to join “The Young Victoria” as their Art Department assistant. After that introduction to the big studio system I transitioned towards independent film, hoping it was a better route to becoming a Production Designer.

Production design of “Hanna” by Carly Reddin.

Kirill: Going back to that beginning of your professional career, would you say that it was right at the time where the industry started shifting almost completely to fully digital pipelines, including the various jobs in the Art Department?

Carly: When I started in the art department, the use of CAD programs for drawing up sets and 3D modelling was on the increase. We were taught these computer skills at the National Film and Television School, but we also learned the basics by hand, which is really important, as using a CAD program doesn’t just make you a draughtsperson.

Hand drafting is still a great communication tool, although you can’t beat CAD for making quick amendments. When I was on “Hansel and Gretel”, we were designing a Tudor town where everything is built of timber and wattle and daub. As these are organic materials, we found that drawing by hand was quicker and ‘freer’ than drawing in CAD. The hand drawing communicated the materials better.

Kirill: Do you miss the physicality of the pre-digital design process, unrolling that roll of paper, walking around that sketch, taking a step back to look at it from a different angle?

Carly: Not really… I’m more excited about the future than nostalgic about the past. These days, I don’t draft up sets myself, but oversee the drawings of one of my team members. I’m totally inspired by the technology that is available to us these days. StageCraft, the technology that was created by the crew of ‘The Mandalorian’ is a total game-changer, immersing cast and crew inside a CG environment in real time. You can even do scouting in VR like they did for “Lion King”.

Production design of “Hanna” by Carly Reddin.

Kirill: When you join a new production, when you get to those meetings and get on the set, is there anything that still manages to surprise you?

Carly: Yes, all the time. If you’re working on a new project, with a new director and team, the process and experience will be different from the time before. Every director has a different approach, for example; Some directors talk with you about the characters, and they’re open to your input. And other directors talk more about mood and tone, and they don’t talk about the characters’ back-stories. Each project is so unique, and there are always surprises. Because of all the wonderfully different people that work on films/TV, there is a different chemistry each time. It’s unpredictable, and I love that about my job. No two days are ever the same.

Kirill: Do you see people walking away, maybe because what they expected from it didn’t quite match that daily routine of this field?

Carly: Some people do find it difficult, because it can be very ‘full-on’. It’s not for everyone. You do have to find the balance between your personal life and your work. In a way, you’ve got to be built for it. The hours can be relentless, but it’s also really fulfilling. I certainly haven’t found another profession that can give me what this job does – in terms of fulfilment and allowing me to be so creative. I get to use both sides of my brain in this job. I have to balance budgets, track spreadsheets, build schedules, etc., and then on the other hand I get to consider colours, textures, mood. It’s a really great mix.

Production design of “Hanna” by Carly Reddin.

Continue reading »

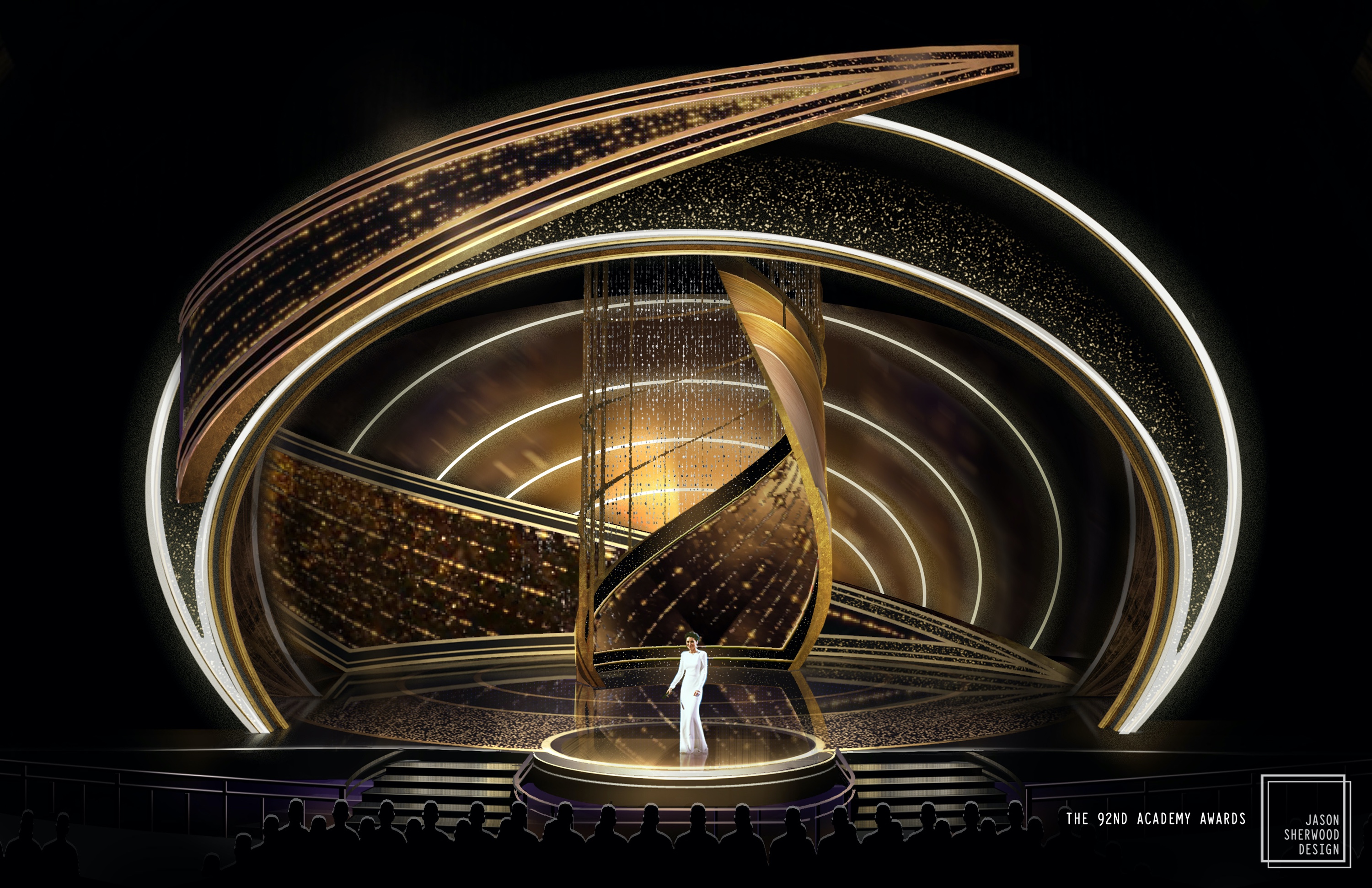

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, and this time extending it into designing live productions, it is my pleasure to welcome Jason Sherwood. In this interview he talks about what goes into designing sets and stages for live performances across a variety of genres, going back to his work on music tours for the Spice Girls and Sam Smith, to Fox’s “Rent: Live”. Jason also takes a deep dive into what went into designing the main stage of this year’s Academy Awards for which he has been recently received the Emmy nomination for outstanding production design for a variety special.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Jason: I’m Jason Sherwood, and I’m a production designer. The focus of my work tends to be in live performance – theater, live television, music performance for television, music performance in stadiums and touring arenas, shows, etc. It’s around things that are either filmed and broadcast, or performed live.

My initial interest in production design and set design was derived from an early love of books, of reading, of writing, and a love of the theater world and a love of graphic design. When I was a young teenager, I was looking for a way to be a part of the theater world, which obviously requires a certain understanding and facility with language, with reading plays, and understanding text and dramaturgy.

I grew up near New York City. My parents would take me in to see Broadway shows, and I fell in love with the beautiful, ephemeral and magnetic quality of a wonderful stage performance. So I began to identify that as a possible career path, and that was at the joining of several different interests of mine. That led to an education at NYU for undergraduate school, and a bunch of internships and apprenticeships, and then jobs as an assistant and associate for several established designers. And then a career on my own as a designer began in my early 20s, which has lasted until now at the age of 31.

Kirill: Why it is your preference to focus on performances that are live in nature, be it taped for broadcast, or live in theater or concerts?

Jason: There’s something truly magical about having to perform the entire production, or the magic trick or the moment, without being able to cut away or fix something in post. It creates this rare alchemy where the audience and the performer are experiencing something singular. Even a Broadway show which runs eight performances a week is different in some form every night, and certainly over time it really changes. That ephemeral nature of a thing that is live is what interests me the most. It’s the way that we can do it again and again, and it will always change based on who is in the room, or who is singing the song, or what city it’s being performed in.

There’s something about the liveness of it that can’t be bottled. You can’t capture it. And of course, when you go back and you watch something that was performed live that has been recorded, it carries that sense of spontaneity. But it’s just not the same as what a live thing is. The work that filmmakers and folks who create television shows do is incredible, but I personally am attracted to this particular challenge. You have this much amount of space, this much amount of time, and you cannot cheat. You cannot augment later. It has to somehow occur in front of the audience’s eyes, and that’s a challenge that I enjoy the rigor of.

Production design of the Oscars 2020 awards show by Jason Sherwood.

Kirill: Do you think that we as humans have a built-in need to tell and hear stories? Is that how we as the audience can “buy”, so to speak, into the make-belief fantasy world that you are building on that stage?

Jason: Stories reflect human experience. You see a play, you watch a movie, you’re told a story, and it feels incredibly real. It’s visceral, and it almost feels uncomfortably related to your own experience.

Humans naturally congregate. They come together, they form communities, and those communities speak to each other. Those conversations are stories. Those stories create discord. Those conversations around the discord create empathy, and that’s how people grow as groups of people. Ultimately, the need to come together to tell stories is inherent, and the varying degree of “substance” that they have within them speaks to capacity for entertainment or interest.

There is something within us as people that requires us to tell stories, and that relates to music, theater, television etc. And that goes to the way we relay our relative histories. That concept is an inherently human idea, and that’s why we keep coming back to it.

Continue reading »

![]() John: It needs to be layered, absolutely. It really depends on what we’re trying to do. For certain parts of entertainment world, that hyper-photo realism is essential. There you need that hyper frame rate with 8K level of detail and the focus on creating a feeling that it’s real.

John: It needs to be layered, absolutely. It really depends on what we’re trying to do. For certain parts of entertainment world, that hyper-photo realism is essential. There you need that hyper frame rate with 8K level of detail and the focus on creating a feeling that it’s real.![]() Arissa: When you’re trying to create something new with a director that has a vision that’s never been done before, you want to get it as close to real as possible. But sometimes there’s no bar to gauge that against. It depends on the task that you have been given, what that collaboration looks like, and where you get to with the final product.

Arissa: When you’re trying to create something new with a director that has a vision that’s never been done before, you want to get it as close to real as possible. But sometimes there’s no bar to gauge that against. It depends on the task that you have been given, what that collaboration looks like, and where you get to with the final product.![]()